Earlier this month, the city and province announced that they will team up to invest $37.5 million in Montreal’s libraries, with plans to create five new ones, renovate others, hire more people and expand collections. There’s still no word on where the new libraries will be built, but this raises an important question: what makes a good library?

I think the success of the Grande Bibliothèque testifies to the need for good design and a good location. Only a handful of people use libraries because they absolutely must; most do so by choice, looking for a good place to spend time or to participate in some kind of community or cultural event. The best libraries unite a large cross-section of people through the effectiveness of their design and the quality of their services and collections. Bad libraries, by contrast, fail to become truly public spaces. Like Montreal’s old central library before it moved into the Grande Bibliothèque, they exist only on the periphery of the public’s consciousness.

Unlike many other Canadian cities, Montreal has a lacklustre library heritage. In the early twentieth century, when other cities were building grand public libraries, often with the help of philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie, Montreal’s Catholic orthodoxy discouraged reading and frowned upon the establishment of places that facilitated it. Even Carnegie was rebuffed when he come to Montreal and offered to empty his pockets for a new library. Until recently, Montreal’s best libraries were privately-owned and operated, like Westmount’s Atwater Library or NDG’s Fraser-Hickson Library. Even when Quebec joined the Canada-wide move towards social democracy in the 1960s, going much farther than other provinces in the realms of health care and education, it failed to invest significantly in public libraries.

That began to change in the 1980s, when Montreal opened some of its most interesting neighbourhood libraries. The Côte des Neiges Library, which won an architectural award after it opened in 1983, is ideally located in the most bustling part of the neighbourhood, right at the junction of the blue line metro and the busy 165 bus. Walk inside and it feels like the heart of Côte des Neiges: energetic and multicultural, with a multilingual collection that weighs heavily on books in Spanish, Chinese and Russian.

Contrast this with the Plateau library, a tiny, embarrassingly makeshift space for a neighbourhood that has such a rich literary heritage. (It is especially sad considering the pleasantness of the nearby Mile End Library, housed in nicely renovated Anglican church.) The Plateau borough mayor, Helen Fotopulos, has said that she hopes the Plateau will be one of the boroughs targeted for a new library.

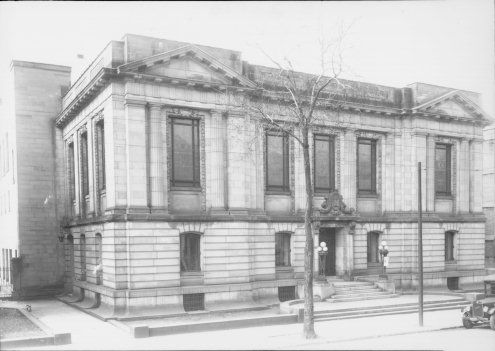

On a somewhat related note, the old St. Sulpice Library, a gorgeous Beaux-Arts building that was vacated by the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec when it moved into the Grande Bibliothèque in 2005, has been bought by a consortium of investors that hope to turn it into a bookstore. It’s a bit of a shame it was kept in public hands, but I can’t think of a more appropriate commercial use for the space.

Photo: Bibliothèque Saint-Sulpice, 1936. Ville de Montréal

9 comments

I hate to disagree with an article I largely enjoyed but I must take exception to the sweeping assertion that Montreal’s Catholic orthodoxy “discouraged reading”. The Catholic Church or parts of it may in the past have preferred church run to secularly run libraries and other institutions but in Quebec as in Ireland and elsewhere this sometimes reflected a real or perceived Protestant bias in secular institutions. The broad assertion that reading was discouraged, based on a link to an article on the list of prohibited works cannot be sustained and I am sure was not intended to offend. I had a traditional Jesuit Catholic education in Ireland where the priests encouraged us to read widely and to debate and to disagree with them. Sometimes unintentionally English Canadians use phrases loosely like this whether relating to language or religion and then wonder why French Canadians feel distant from them!

I certainly didn’t mean to offend. You’re right that there was certainly was a Protestant bias in many of the libraries that existed at the time. But, at the same time, you can’t deny that there was a very concerted effort by the church between about 1890 and 1920 — right during the library boom elsewhere — to restrict what ordinary Quebeckers were reading.

A “traditional Jesuit Catholic education” like the one you describe was reserved mainly for the children of the elite. Public libraries, however, were designed to do precisely the opposite: bring literature to the masses.

In any case the Montreal clergy, always among the more conservative in Quebec, were very adamant in their refusal to support any sort of public library system. The Carnegie story is a telling example. In 1902, at the request of Montreal’s mayor, Raymond Préfontaine, he offered the city $150,000 to build a library. After nearly two years of discussions, though, church officials made it clear that they would not tolerate any library over whose content they had no control. Realizing that any attempt to build a public library would be fruitless, city council finally decided to abandon the matter in 1903.

Here’s a front-page story from La Patrie on the library question, explaining the motives behind rejecting the Carnegie money, and here’s a letter published in the New York Times in 1913 offering a similar take on the matter. (Watch out, they’re PDF files.)

I found Donal Hanley’s comments extremely interesting. (translation: ill-informed.)

Catholicism in Quebec is very different from Catholicism in Ireland, and I don’t think they can be adequately compared, especially when it comes to literacy and libraries. Chris had it right when he said that Montreal’s (Quebec’s!) orthodoxy discouraged reading. CBC Radio has done at least 2 stories on this subject in the past 3 or so years.

Montreal’s library system is pathetic, especially considering how incredibly literate this city is – I have never seen so many people reading on the bus and in the metro, but most of them probably have bought their books instead of getting them from the library.

This has nothing to do with English Canadians misusing a phrase – I am almost positive that all of the francophones I went to libray school with would agree that the church had their hands in Quebec libraries. This is not an English vs. French issue – it’s a church-based form of censorship that the people of Quebec did not put up with – they stopped using libraries and started buying books instead.

Chris & Carrie

Thank you both for your replies. I know, Chris, that you did not intend to offend. And Carrie, I admit I am using an analogy between Quebec and Ireland that may not hold up. It seems no one disputes Chris’s assertion that the Catholic clergy in Montreal “were very adamant in their refusal to support any sort of public library system”. Had the original article simply stated that fact, it would not have occurred to me to post a comment!

I’ve been a regular reader of this spot for a few weeks now, and I must say I’m impressed with Chris’ thoroughness and research skills.

A part of Montreal’s public library history worth mentioning is the small branch that existed on the mezzanine to McGill metro (photo of the library)

hi chris, nice article… perhaps you could add a link to the atwater library mentioned above? http://atwaterlibrary.ca

Omitted entirely is any mention of Montreal’s FIRST free public/style private library, the Fraser-Hickson, recently closed because of lack of priority by CDN/NDG Mayor Michael Applebaum.

Opened at the the time of Prime Minister John Abbot, friend of lawyer Hugh Fraser, who bequeathed a sum of money to start a “free public library, museum and gallery”, open to people “of every rank in life, without distinction, fee or reward of any kind.”

For the 57 years it operated on Kensingtion St. in NDG, it provided services woefully lacking in the borough, particularly for anglophones, but actually surpassing services offered by city libraries. Books, videos, cds, historical tomes and documents in an antiquarian collection were available in it’s spacious premises. An auditorium was available for community use, plus computer courses were offered for a nominal fee.

Due to financial troubles, plus an unwillingness of the borough to invest in what they consider a private library, a sale to a private school ensued in October. The shut-in service, unique to this library,is still manned by faithful volunteers, providing a lifeline for those most isolated in the community.

Community activism managed to save the building from demolition or change. A mural by Louis Archambault, called the Seeds of Knowledge, designed in collaboration with the architect, along with a sculpture by Gord Smith and an indoor mural gracing the entrance of the former Children’s Library are among the historic features that have been preserved.

The Fraser-Hickson is currently looking for suitable locations to open. Residents of NDG hope the library will remain in the borough, although there is nothing, aside from the desire of the community, to prevent it from reopening elsewhere in Montreal.

A.Ronald

for further information, see http://www.fraser-hickson.qc.ca

I agree that libraries should be cultural centres and not just warehouses for books. Indeed, during the Winter, there are few cost-free places citizens can retreat to. Hopefully, when the Fraser-Hickson is re-opened, the parameters such as you’ve outlined will be taken into consideration.

I do take issue with the SERIOUS inadequacy of the BNQ’s English language collection. Next time you visit, go to the children’s section and look in the area “bandes dessinées” (Comic strips). It is a large field of cases containing many hundreds of comics. However, there is a TINY case—you have to see this to believe it—of English language comic books (a very popular way for kids to learn to read). I am not an English rights activists, but when you behold this sight, your blood will most certainly boil.

A recent CBC report places the acquistion of English books in the municipal system at 7% (grossly below the percentage of anglophones and francophones who need or want English books). An embarrassed librarian at the BNQ (of ethnic origin) even admitted he felt that it was a political decision. There is no excuse for this wanton insult to those who want to learn the English language. And until it is resolved, the BNQ should not be considered a Marvel of any kind.

can you please name and expanciate what the component of a good library are. I am waiting.