It wasn’t until the 1950s that Canadian urban regions had the economic might to build modern cities. And what an intriguing legacy that era left us

The Canadian landscape has been easy to define because it’s so much a part of our national identity: wilderness, rural, water; repeat. Trying to define the Canadian cityscape is much more difficult, as our traditional Canadian identity has totally avoided cities, even though these are where most Canadians live. Try picturing “The Canadian City.” If you can conjure up something that represents the whole country, you’re a visionary. There are certainly landmark buildings and neighbourhoods across Canada that are famous for their striking images, such as the multi-coloured clapboard houses of St. John’s, or the walled Old Québec City. Distinctive cityscapes are an important part of the Canadian identity, but they are in no way typical of a wider Canadian style of urbanism.

So we’re back to a difficult starting point: trying to find connections across the country. Canada is far too spread out geographically, with too much variety in building materials, to have an overwhelmingly consistent look to our cities. Though there are many similarities between Canada and US, the latter had a growth spurt much earlier than Canadian cities, so many American cities have a fair amount of “City Beautiful” architecture — a monumental style popular in the late-1800s and early-1900s, when government and institutional buildings were built, often along grand avenues. This lent city centres, from New York to San Francisco, a somewhat consistent look.

Except for cities that developed early on like Winnipeg and Montréal, only a smattering of City Beautiful buildings exist in our cities. In 1904, while the United States was in the middle of its City Beautiful boom, Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier made his famous speech about looking towards the country’s next 100 years: “Canada has been modest in its history, although its history, in my estimation, is only commencing. It is commencing in this century. The 19th century was the century of the United States. I think we can claim that Canada will fill the 20th century.”

We haven’t come close to fulfilling Laurier’s dream, but we had a late start. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the built form of the country really began to expand, as two wars and the Depression left only a scant decade or two when the economics were right for growth.

Looking across the country with this in mind, and setting aside those historic downtowns and celebrated leafy Victorian and Edwardian neighbourhoods, an incredible amount of Canadian urbanism was created during the mid-century boom, just after World War II until the recession of the late 1970s slowed things down. This era of growth defined downtowns with skyscrapers and other commercial buildings, as well as provided strip malls and modernist bungalows to the suburbs. Yet we hardly talk about this.

Not noticing this aspect of our landscape is a common phenomenon. In the opening of the incredibly rich book Winnipeg Modern: Architecture, 1945-1975, editor Serena Keshavjee commented that though that city has some of the finest mid-century buildings in the country, she was initially caught off guard by them. “When I moved from Toronto to Winnipeg during the summer of 1996, I was prepared for the splendour of the Exchange district, which was declared a National Historic Site by Sheila Copps soon after I arrived. I was not expecting to find, however, the fine stock of mid-century modernist buildings throughout the city. I grew up in Don Mills, the paradigmatic, planned North American modernist neighbourhood, a suburban-style Garden City, with local parks, schools, and shops. Don Mills is well known for its modernist buildings and gets lots of attention for it. No one ever mentions Winnipeg modernism.” Yet there is was in plain sight, unacknowledged. Not unlike how Canadians approach a lot of cultural things.

Some of our modernism is not particularly beautiful and is actively forgotten for a reason, but there were also plenty of Victorian and Edwardian structures that weren’t pretty or were poorly built that nobody lamented losing. Everybody forgets about the junk, like that false adage about antiques says: “they don’t build them like they used to,” a notion that requires overlooking how people threw out junk and only the good stuff survived. This is one reason we fail to recognize the modernist landscape that connects and defines so much of Canada: a fair amount of it isn’t pretty and was built on the cheap, and simply hasn’t been torn down or revitalized yet. One ugly, unfortunate building can be enough to obscure an entire area. More importantly, Canada’s modernist heritage isn’t talked about because it’s in the teenage phase of its existence, awkward and unloved, the same phase that now-beloved Victorian and Edwardian buildings were in after the war, when nobody cared for the frilliness of those older styles and when the fashion of day was all-mod-cons and atomic age forward thinking.

Fashion is fickle and destructive though. It was during the immediate decades after the war that we lost a lot of older, unfashionable buildings to the destructive forces of the modernist boom. A lot of the junk went, but so did many of the buildings that have us lamenting or scratching our heads, wondering how we could have ever torn them down. The destruction of the Van Horne mansion in downtown Montréal for a modernist tower in 1973 was emblematic of this kind of push for removal, one that also included urban renewal schemes and expressway plans in many of our major cities, all of which resulted in organized resistance. In the Van Horne case, the “Save Montréal” movement was born, while in Toronto a similar group coalesced around stopping the Spadina Expressway. These groups and others across the country may have had a particularly Canadian way of tempering the most destructive modernizing forces before too much was lost.

Graeme Stewart, a Toronto architect and modern heritage preservation activist says that the anti-modernist reaction has meant that there hasn’t been much popular exploration and recognition of this aspect of Canadian cities, and what work on the subject does exist is paradoxically related to what modernism got wrong. Speaking about Toronto specifically, Stewart says that “prior to the recent boom of writing about the city there is quite little, and what does exist is largely a result of the wonderful, yet anti-modern, reform movement. Not many books were written during the postwar boom as observations or retrospectives. The general history of Canadian architects books seem to focus on the big guys like Toronto Dominion Bank, and generally ignore the ‘fabric’ modern architecture like schools, housing, shops that really defined the era.”

The recent boom Stewart speaks of is related to the growing modernist preservation movement in Toronto that the firm he works with, E.R.A. Architects, has helped lead, co-produceding the books Toronto Modern and Concrete Toronto with Coach House Books. What these and other publications have done is sound a warning that modernism is at an age when it faces the same risk of becoming as unfashionable as the Victorians and Edwardians did in the decades after the war, when the risk of demolition was greatest. This isn’t to say everything modern is great and worthy of a glossy spread in Canadian Architect, but in recognizing how much this era defines our cities we can more honestly access what has worked and what hasn’t.

With this in mind, casting an eye across the country, our modern urban fabric seems much more apparent, and those older downtown neighbourhoods, by comparison, seem a much smaller part of what the Canadian city looks like. Buildings built between the 1950s and ’70s generally dominate the skylines. In Halifax, the historic waterfront is still there, but what folks from Dartmouth notice are the modernist office towers. Old Québec City — save the Chateau Frontenac — is dwarfed by the buildings adjacent to the Plains of Abraham outside the walls, and the downtown is mostly modernist in nature. Similar skylines exist in Vancouver, Hamilton, Toronto, and other cities. Edmonton’s North Saskatchewan River valley is overlooked by an incredible line of mid-rise apartment buildings, from the legislature to the end of Jasper Avenue, much like Central Park in New York.

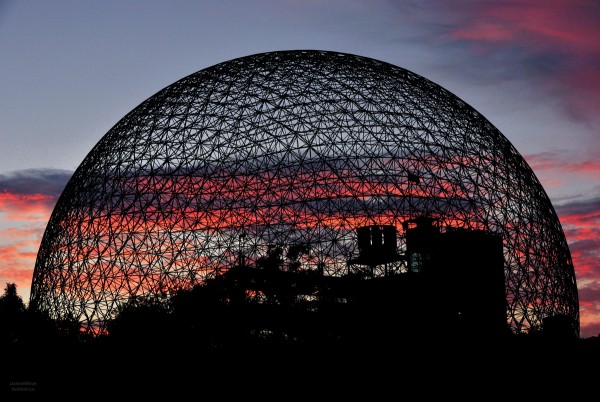

Two buildings that house public utilities, built just a few years apart, represent the kind of pride felt during the optimistic modernist age, and can be thought of as modernist totems of sorts. In Montréal, along what became René Lévesque Boulevard, the 1962 Hydro Québec building rose a few blocks north of the old city, complete with its lightning bolt Q logo. In the fantastic book, The 60s: Montréal Thinks Big, published to accompany a 2004 exhibition of the same name at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, the construction of the Hydro building was said to symbolize “the achievements of the state in the service of Québec Society,” a kind of concrete version of the Quiet Revolution. Perhaps with a bit less nationalism but equal amounts of pride, Vancouver’s Electra Building opened in 1957 as home to BC Hydro (though now it’s converted to residential). In both these buildings, the exploitation of national resources, a very big part of the traditional Canadian identity, is represented in a most central urban context, so a connection is made between the landscape and urban Canadian identities.

Two other notable modernist buildings have a connection to the traditional identity as well, this time in the realm of transportation. The CPR and the Last Spike are part of our founding mythology, so it makes sense that the second time Canada was bound together by air travel it manifested in an impressive, jet-age way. In Toronto, Aeroquay One was completed in 1964. Designed by preeminent Canadian modernist John B. Parkin, it was a terminal in the round where people could park in the middle, walk only a hundred metres and be at their gate. Also opened in 1964 was Winnipeg’s airport terminal designed by GBR Architects. Both gems are sadly demolished due to the incompatibility of their jet-age elegance with today’s mass transit requirements.

The construction of skyscrapers, along with massive events like Expo ’67, are just one part of Canada’s modernist landscape. So much of that everyday fabric Graeme Stewart talks about continues to be a living part of our cities. Across the country, major chunks of infrastructure — unglamorous roads and bridges, or sexy subway stations in Montréal that, at times, match Expo ’67 in capturing the spirit of the era — still help the country run. Many Canadians went to school in midcentury buildings with terrazzo floors, open concept rooms (often later divided into classrooms), and walls of windows. These schools can be found across the country, still in use and in varying states of care (vintage schools are at high risk of being lost, as heritage preservation is a low priority for boards of education).

The modernist era also saw tremendous growth in post secondary institutions across the country. Many universities and colleges feature some of the most avant-garde modernist designs in Canada. Older campuses got new buildings added while entire new universities like York, Simon Fraser, and Trent were created from scratch. Brutalist UQAM in downtown Montréal was woven into the urban landscape. Architect Arthur Erickson’s dramatic University Hall, set into the hills around the University of Lethbridge, is another connection between traditional images of Canadian landscape and new, modernist buildings. Another monumental Erickson work in Vancouver, the Law Courts, dominates the middle of the downtown peninsula like a human-made hill.

Modern city halls, libraries, apartment buildings, cul-du-sacs full of split-levels and ranch houses, community centres, churches, department stores, and entire underground cities in Toronto and Montreal plus a +15 elevated pathway system in Calgary — these elements add up to an overwhelming amount of modernist geography. Though often loathed for either planning mistakes or subsequent decline in care and maintenance, Canada’s public housing stock is largely modernist, from individual buildings to entire neighbourhoods that include Lord Selkirk Park in Winnipeg, Habitations Jeanne-Mance in Montréal, and Regent Park in Toronto (though this is currently being revitalized with entirely new buildings).

Some neighbourhoods in Canada blend modernism and prewar elements into charming and walkable areas. South of downtown Calgary, the railway corridor cuts just below skyscrapers beyond which is an old industrial warehouse district that has become, as these places often do, an entertainment and “creative class” district mixed with apartment buildings from 10th to about 17th Avenues.

South of 17th Ave. is a remarkable swath of fairly dense residential housing that includes older homes and modernist (and newer) low-rise apartment buildings. Like Los Angeles, there is an unexpected leafy kind of thick urbanity here. Walking down a sidewalk, an older home from the 1920s could have a post-war modern low-rise apartment building as a next door neighbour.

In 2005, I was in Calgary for a week and became friendly with a Calgarian who whisked us in a minivan north across the Bow River to the Crescent Heights neigbourhood. Another nice mix of pre and postwar residential homes, our destination was a party in a modernist bungalow. We’re taught to think these are homes to nuclear families, but inside there were some twenty-something professionals living communally, surrounded by expensive home entertainment electronics: a $20,000 video camera, the first domestic plasma TV I had ever seen, and other luxury toys for adults. Our host whispered “oil money,” which seemed to explain everything. The ability of modern homes to adapt to different modes of living, just as prewar houses do, is evidence that mixed living patterns can be replicated in modern neighbourhoods, too.

As Robert M. Stamp writes in his book Suburban Modern: Postwar Dreams in Calgary, the city embraced modernism well after WWII. They redefined it and built residential architecture accordingly: “They moved modernism out of the studios of the avant-garde producers and into the hands (and hearts) of the middle-class consumers, out of downtown art salons and design studios and onto the streets and into the suburbs [… ]and redefined modernism to include modern homes in modern suburbs, with modern furniture and modern appliances and modern cars. For postwar Calgarians, modernism meant personal betterment, achieving all those material gains that had been delayed or denied by 15 years of depression and war.” Years later, it remains a solid and defining part of Calgary.

This is how we live as Canadians. We are all touched in one way or another by modernism, where we live, play, or conduct business. Is there another element in Canadian cities that is so common? Focusing on our shared modern experience may be a start in uniting the country around its similar urbanity, rather than focusing on the plague of traditional regional divisions.

![]()

Shawn Micallef is a senior editor at Spacing. He is the author of Stroll and Full Frontal TO, both published by Coach House Books and writes a weekly column for The Toronto Star

Shawn Micallef is a senior editor at Spacing. He is the author of Stroll and Full Frontal TO, both published by Coach House Books and writes a weekly column for The Toronto Star

This article appears in the Spring 2013 issue of Spacing (national edition)

photos by Brian Carson (Habitat 67 in Montreal), Mark Hanoi (Riverdale Hospital), Adam Fagen (Hydro Quebec), Steve Scrambler (University of Lethbridge)

7 comments

I refuse to be moved to nostalgia for the sake of modernist monstrosities like Erikson’s University Hall in Lethbridge or his horrendous law courts in Vancouver. The concrete bunker of University Hall is so depressing and monotonously dreary it literally drives students to suicide, and the law courts are built seemingly as an deliberate insult to anyone unfortunate enough to pass by on foot. In my opinion, blank, windowless concrete walls will never be an architectural form worth celebrating or preserving. Buildings are built to live in, not so that frustrated sculptors with architecture degrees can find their forms “dramatic”.

Architecture drives students to suicide. Keeping the criticism hyperbole free!

I’m sorry my tone was extreme, but I honestly don’t think my comment was hyperbolic. Have you ever been in the first year residences in the basement of University Hall at U of L? Low ceilings, bare concrete and a lack of windows are not the best surroundings for young people undergoing a stressful period of life change.

One unfortunate loss—Killam Library, Halifax’s best brutalist building, is supposed to be reclad in glass within the next few years. Most students hate the building, especially the way it contrasts with the older Georgian-era buildings on campus, but it’s in the fine tradition of big fat brutalist university libraries (see also: Robarts). And it’s very elegant, actually.

The notion that brutalist campus buildings drive students to suicide is an urban legend that I’ve heard repeated about every school that has such buildings. One may not enjoy brutalism, but it is only one type of modernist architecture. There are many elegant, livable, light-filled buildings that I think we generally don’t notice because they’re so much a part of the cityscape that we take them for granted.

I’m fortunate to work in a Parkin building, 200 University Avenue. Huge windows, elegant proportions, and it still works very well for offices all these years later. The high, minimally detailed lobby always gives me a lift in the morning.

I find the University Hall in Lethbridge quite beautiful given the surrounding context and landscape. It gives somewhat a space/alien look that tells a story (somewhat similar to those at SFU). Indeed, the interiors may need renovation and a fresh look, but that can be fixed without the need for demolition. There is also tons of opportunity to take good use of those blank walls for bold art and lighting.

I wonder how we will look at today’s new buildings in the future? In contrast, I feel little connection architecturally with many of the “fancy”/expensive condominiums (baring a few) being built everywhere.

Spent two degrees and 6 years inside University of Windsor’s brutalist library and it was a very good place to work. Safe, solid.

Some people don’t want to be in libraries so they look for things to blame, like the concrete.