It’s been said to me that City Hall is run by engineers and lawyers. The engineers determine whether a given idea is technically feasible. The lawyers, on the other hand, dictate whether the City has legal authority to take a decision and assess whether the liability of a particular decision is manageable or not.

This last piece — the determination of how to manage liability — is what can often make our public spaces and interactions feel like they’ve been suffocated.

Take street hockey. As someone who grew up playing one of the best manifestations of Canada’s national pastime, it didn’t strike me for a moment that I was breaking a by-law. Yet, according to the rules, I was a scofflaw by the age of eight.

Criminalizing street hockey is an absurd idea to most of us but as Councillor Josh Matlow recently found out, to legalize the game means getting through the City of Toronto’s lawyers. As his recent comments suggest, Matlow’s reasonable proposal to legalize a favourite sport of kids across Toronto turned into a bureaucratic nightmare once the lawyers sunk their teeth into Matlow’s ideas. The lawyer-approved process for legalizing street hockey on your block includes petitions, traffic studies and community council approval, a process that is more imposing than the presently unenforced ban.

Though council is not obligated to listen to its lawyers, for fear of exposing the City to liability, council often sides with its legal staff’s recommendations. But the question that continually goes unanswered is whether city council is getting reasonable advice from its lawyers. Is the risk of the City being sued in the event of an accident involving street hockey really so great that it’s worth making the game illegal? As a lay person, I have a hard time believing that the answer to that question could possibly be “Yes.”

I’m not allergic to government regulation but whether it’s street hockey, street food, reasonable cycling laws, or any number of other things, the City of Toronto’s lawyers appear ready to throw a wet blanket on Torontonians at every turn under the guise that even common uses of public space expose the City of Toronto to legal liability. So I think it’s time that, instead of continuing to spend millions on consultants to conduct fruitless “core service reviews,” City Hall hire a team of outside lawyers to comb over the by-laws that govern Toronto’s public spaces to find out which of these bubble wrapped regulations are truly necessary, and which ones keep us from the reasonable enjoyment of our city.

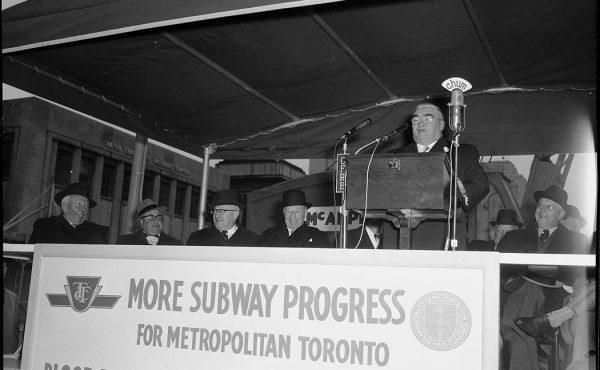

photo by Doug Caribb

5 comments

I’m not a legal scholar, but I’ve always been struck by these roads in rural Ontario that are considered to be “unassumed”. They’re not privately owned, but since they don’t meet the minimum design requirements for municipal assumption, the municipality absolves itself of the risk and sticks a sign saying that you should use it “at your own risk.”

Maybe some sort of legal gray zone like this for some of our public spaces might be a good place to start.

The problem is that the City is always seen as a “Deep Pockets” target for lawsuits even if they are only marginally-connected to the case

What would the City pay if street-parked vehicles were damaged by pucks, balls, etc..? I think the current “unenforced” by-law is designed to avoid those kind of liability suits.

Not pretty – but it’s probably cheaper than the damage and legal costs of the alternative

On a similar but completely different topic, I took the Toronto island ferry this weekend. Anywhere near the railings or water views was cordoned off. Probably 50% of the floor space is now usable since the other 50% is so terrifyingly dangerous. The last place I saw a double fence structure was between me and the tigers at the zoo, and that was probably for the tigers benefit.

The absurdity of how easily everyone ran away from the idea when staff waved some red tape in their face is that these staff recommendations come from the same staff who didn’t want to do anything about it in the first place. Coming up with obstructionist rules is the typical next step from staff who don’t want to do anything. It’s the job of politicians to keep pushing them until they come up with something reasonable – a job our politicians completely abnegated in this situation.

In Kingston, the opposite happened – staff resisted, but the politicians kept pushing until a good proposal was developed and implemented.

I’m also dubious that a bylaw that politicians actually boast is deliberately unenforced would be a protection against liability if a case actually went to court.

The bit that gets me is that the presumed danger from both the engineering and legal standpoint is often based on outmoded standards describing how things “should” work, instead of objective reality.

When drivers know there will be kids playing on a street, they act appropriately and pay attention to what they’re doing. When they’re told that the road is theirs alone, and the street is built only for their needs, they drive faster and less carefully. Slower-moving traffic is inherently safer for everyone around it.

Yet there is never any question about liability on the City’s part for transforming local streets into car-exclusive roads filled with inattentive speeders.

http://grist.org/article/2010-11-22-confessions-of-a-recovering-engineer/