It was 1832. William Lyon Mackenzie was fed up. He’d spent the last decade fighting for democratic reform in Upper Canada. He’d founded a pro-democracy newspaper. Written passionate editorials. Led protests. Organized committees. He’d even run for office and been elected to the provincial Assembly, where he gained a reputation as one of the most radical champions of the Reform cause. This was before he became the first Mayor of Toronto — and long before before his failed revolution — but he was already one of the most polarizing figures in the province. Still, no matter how famous he got, he was blocked at every turn.

Upper Canada was still pretty new back then. The province that would one day become Ontario was only a few decades old. It had been founded in the late 1700s as a safe haven for refugees from the American Revolution. During that bloody war, they’d seen for themselves the horrors committed in the name of democracy. And it was followed closely by the terror of the French Revolution. So, many of the early settlers in Upper Canada had a deep distrust of democratic ideas — what the first Lieutenant Governor, John Graves Simcoe, once called “the tyranny of democracy.”

Even now, in the 1830s, Upper Canada was a very conservative place. Most of the power in the province was concentrated in the hands of a few democracy-hating, monarchy-loving Tory families. “The Family Compact,” Mackenzie called them. They fought hard to maintain the status quo. Those who argued in favour of democratic reform tended to find themselves in jail or in exile. And if Mackenzie and his Reform allies ever did manage to pass a motion through the elected Assembly, the British Lieutenant Governor was there to veto it.

Sometimes, things even got violent. Years earlier, Mackenzie’s home and business (in Toronto, still called York back then, on Front Street at Frederick) had been attacked by an angry Tory mob. His family hid in fear as the young rioters — dressed in a parody of First Nations clothing — trashed the newspaper office, broke the printing press and tossed the type into the lake. Mackenzie sued and used the settlement to set up an even bigger operation. But things still weren’t getting much better.

So Mackenzie came up with a new plan. He had been inspired by American and French writers and thinkers who launched all out war against their own governments, but he wasn’t planning on going anywhere near that far himself. While others had assembled armies and wheeled out the guillotine, he was still hoping for a peaceful resolution. He still believed in the British system. If he could appeal directly to the British government — if he could present them with his grievances in person — he was sure they would listen to reason. So Mackenzie decided to pay them a visit. He would go to London himself.

He spent much of 1831 getting ready for his big trip. He travelled all over the province, meeting people, making speeches, gathering support, collecting signatures for petitions. When he arrived in England, he planned on having a mountain of evidence to support him. Meanwhile, he kept up his propaganda campaign against the Tories and the Family Compact, calling them names, interrupting their meetings, demanding change, and generally being a thorn in their side.

The Family Compact struck back. That winter, the Tories in the Assembly voted to kick Mackenzie out of office. It sparked a crisis that lasted for months. A mob of Mackenzie’s supporters burst into the Assembly and demanded new elections. The Lieutenant Governor refused. But in the by-election that followed, Mackenzie was re-elected in a landslide. Only one person in his riding voted against him. A victory parade of more than 130 horse-drawn sleighs marched down snowy Yonge Street to the sound of bagpipes, bringing their democratically elected representative back to office.

Five days later, the Tories kicked him out again. There was another by-election. And another landslide victory for the famous Reformer.

Mackenzie went back on the attack, pissing even more Tories off. During a visit to Hamilton, he was beaten by thugs and left bloodied in the street. In Toronto, he was pelted with garbage and burned in effigy. Riots broke out. His newspaper office was attacked again. Mackenzie feared for his life. He was only rescued thanks to Colonel FitzGibbon — a Tory hero of the War of 1812 who would one day lead an army against the man he had just saved.

Mackenzie was so scared, he went into hiding. And he stayed there until spring. Then, as the ice melted, he finally boarded a ship bound for London.

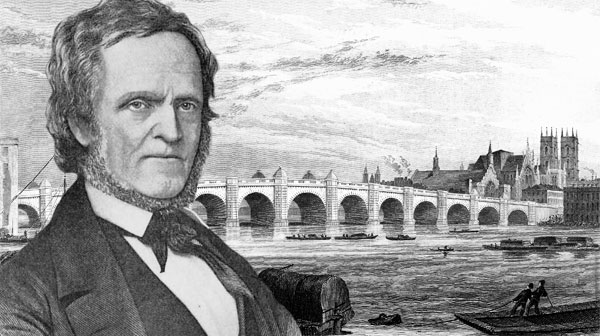

He got off the boat in England at one of the most important moments in modern British history.

London was in turmoil. While Mackenzie had been fighting the Tories back home in Canada, Reformers and Radicals in England had been fighting the Tories there, too. Now, it looked like they might finally be getting somewhere. For the first time in more than 20 years, the Tories had lost an election. The reform-minded Whigs were in power. And they were planning on using it: the Great Reform Act would be a landmark in the history of British democracy, doing away with the “rotten boroughs” (out-of-date ridings with tiny populations that gave wealthy Tories a way to buy a bunch of extra seats). But every time the Whigs passed the bill through the House of Commons, the unelected Tories in the House of Lords killed it. The stalemate was plunging the nation into crisis.

At the very moment Mackenzie arrived in London, that crisis was reaching a boiling point. The Whigs were trying to pass the bill again. This time, they demanded the King appoint new peers to the House of Lords to make sure the bill became law. When the King refused, the Whig Prime Minster (Earl Grey, of tea fame) resigned in protest. The Tory leader (the Duke of Wellington, of kicking Napoleon’s ass fame) took over as Prime Minister.

The country shut down.

They called it “The Days of May.” For about a week it seemed as if anything might happen. As the news spread across the United Kingdom, shops and factories shut down. Political unions mobilized. Huge crowds gathered in protest. There were riots. Westminster was flooded by hundreds of petitions with tens of thousands of signatures. There was an orchestrated run on the banks and people withheld their taxes — for a while it seemed as if the country might go bankrupt. Angry placards and posters lined the streets of London. There were whispers of revolution; as one historian later put it: “the air was charged with talk of pikes and barricades and swords rough-sharpened…”

William Lyon Mackenzie watched it all happen. As the crisis hit London, our future mayor was living just a couple of kilometers from Westminster. He wrote about what he saw in letters published in his newspaper back home in Toronto. He’d seen, he said, the Duke of Wellington, “the hero of Waterloo, pelted with mud and fish heads in the streets of London. Tory peers were hissed, hooted and groaned at as they entered their carriages.”

Finally, King William and the Tories backed down. The Whigs returned to power and the bill was brought to a vote. Tory Lords abstained. Mackenzie was there himself that day, watching from the gallery in the House of Lords as the Great Reform Bill was finally passed.

Inspired, Mackenzie set to work trying to win similar reforms for Upper Canada. He spent more than a year living in London with his family, in cramped quarters with little income and plenty of mounting debt. At first, it all seemed to be worth it. Things were going well. As spring gave way to summer, Mackenzie — along with a couple of other Canadian Reformers — began to have a series of meetings with the Colonial Secretary. It was a major coup: those meetings were hard to get; many leading Reformers had tried and failed. Now, a radical Reform politician from Toronto finally had the ear of the man who oversaw the running of the entire British Empire.

Mackenzie was feeling optimistic. The Colonial Secretary, he wrote, struck him as “friendly and conciliatory… I left him with the impression strongly imprinted on my mind that he sincerely desired our happiness as a colony…” Mackenzie even got to meet Earl Grey, and was left positively gushing about the Prime Minister. “Well does Earl Grey merit the high station and distinguished rank to which he has been called,” he wrote, “truth and sincerity are stamped on his open, manly, English countenance; intelligence and uprightness are inscribed on all his actions.”

The British really did seem to be taking Mackenzie’s complaints seriously. While he was living in London, he was invited to share his thoughts in the major newspapers. He published a book. And when he produced his petitions signed by tens of thousands of Upper Canadians, the documents were presented to the House of Commons with the support of the Whig government. They even asked him to submit a written copy of all of his grievances. Mackenzie responded with his usual passion: he stayed up for six straight days and nights, writing furiously, switching from one hand to the other when the first cramped up.

Even more importantly, the British government started making real changes, accepting a bunch of Mackenzie’s suggestions. The Colonial Secretary sent a stern letter across the Atlantic to the members of the Family Compact. The Anglican and Catholic bishops were asked to resign their seats in the Assembly to further the separation of church and state. The post office, he told them, should be reformed. There should be an independent judiciary. They needed to stop kicking Mackenzie out of the Assembly. And they should publish the letter, so the people of Upper Canada could see for themselves what the government in London was recommending.

But the Family Compact wasn’t about to give up that easily. They sent the letter back, claiming that Mackenzie’s complaints were unworthy of “serious attention”. One of Toronto’s most conservative newspapers, The Courier of Upper Canada, called the letter “an elegant piece of fiddle-faddle, full of clever stupidity and condescending impertinence.” The Tories had already kicked Mackenzie out of the Assembly once since he’d left for London. Now, despite the letter, they did it again.

This time they’d gone too far. The Colonial Secretary responded by firing two prominent members of the Family Compact: the Attorney-General and the Solicitor-General. They’d both been leaders of the campaign against Mackenzie. For a few brief weeks, it looked as if the government in Westminster was finally taking Canadian Reformers seriously.

That was in March of 1833. In April, the Colonial Secretary was replaced. And everything changed. In May, Mackenzie got a nasty shock: as he left a meeting at the Colonial Office on Downing Street, he ran into the old Attorney-General. This was the same guy who had just been fired for his attacks on Mackenzie and his opposition to reform. The fired Solicitor-General would soon be joining him. They had come to London all the way from Toronto to defend themselves and undermine Mackenzie. And their plan was working.

The new Colonial Secretary was much more conservative than the last one. In fact, he would eventually leave the Whig Party to join the Tories. So, as you might expect, he had a very different attitude toward the Tories of the Family Compact. And he wasn’t alone: many Whigs were beginning to change their tune. In England after the Great Reform Act, pro-democracy protests had continued to push for even more reform. The Whigs were losing patience. That same month, police brutally cracked down on a protest near Mackenzie’s house. The tide was turning. And so, the new Colonial Secretary reinstated the Attorney-General and gave the Solicitor-General a sweet new job in Newfoundland. Just like that, Mackenzie’s victory had evaporated. His mission had failed.

“I am disappointed,” he wrote. “The prospect before us is indeed dark and gloomy.”

He left London, never to return.

Mackenzie had plenty of time to think on the long voyage back home across the Atlantic. His faith in the British system had been deeply shaken. And the Colonial Secretary was far from the only person he’d met in London. He’d also spent plenty of time getting to know the Radicals and Reformers behind the democracy movement in England. He was good friends with Joseph Hume — a Radical Whig MP. And during the crisis over the Great Reform Act, Hume had welcomed him into the very heart of the movement. Mackenzie was taken into the back room of a tailor’s shop just a few doors up from Trafalgar Square. There, he met Francis Place — the famous “radical tailor of Charing Cross,” one of the leaders of the reform movement. He was the man behind many of the angry posters in London and the organized run on the banks. The back of his shop had been turned into a library filled with revolutionary ideas. (His collection still exists today, hailed as “one of the finest of its kind anywhere in the world.”) The shop was ground zero for radical politics in England, where politicians and protesters alike came to discuss the ideas they were fighting for.

Place was much more radical than Mackenzie was — even on Canadian issues. So was Hume. They both believed the Canadian colonies should be independent. And that violence was an acceptable solution. If the Great Reform Act failed, Place was planning on leading a rebellion. He’d sent the government his plans earlier that very same day.

As Mackenzie grew more and more frustrated, those ideas were going to make more and more sense to him. He’d gone to England because he believed the British government would listen. But he didn’t believe that anymore. And when he got back to Toronto, the troubled continued. The Family Compact opposed democratic reforms at every turn and the British Lieutenant Governors continued to support them — in one election, the Governor even openly campaigned for the Tories.

Mackenzie grew ever more radical. Within a couple of years, he was publishing a letter by Hume in his newspaper, calling for Canadian independence from the “baneful domination of the Mother Country” even if that meant an armed revolution. A few years after that, Mackenzie took the advice. In the winter of 1837, he wrote a “Proclamation to the People of Upper Canada“. He called for truly fair elections, meaningful reforms, and maybe most telling of all: “An end forever to the wearisome prayers, supplications, and mockeries attendant upon our connection with the lordlings of the Colonial Office, Downing Street, London.” William Lyon Mackenzie was declaring independence.

Two weeks later, he gathered a rebel army on Yonge Street, just north of Toronto, and marched south into the city.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog as part of the Dreams Project’s tour tracing the history of Toronto in the UK. You can find more sources, photos, links and related stories there.