By: Jeff Biggar

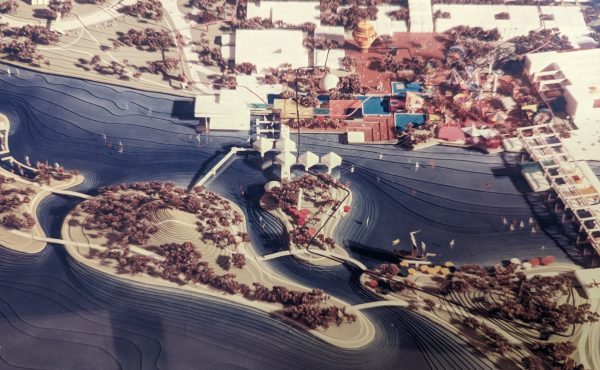

I recently joined residents in Mabelle Park to celebrate ‘Iftar Nights’, a sundown celebration to break the fast during Ramadan. People gathered around a fire, there was a musical performance, crafts for children, and a much-anticipated watermelon smash. The evening ended with a light meal prepared in the community kitchen of a nearby apartment tower that overlooks the park. The celebration was organized by MABELLEarts, a community arts organization that has worked for 10 years with Mabelle residents to restore and reclaim the park, which is situated in the middle of a Toronto Community Housing complex in Etobicoke.

Toronto has seen a proliferation of public art in recent years, most of which is object based sculptural work. Supportive public art policies have brought new works to certain parts of the city, but policies mostly tie art to a specific building more than a wider community, despite art being considered a ‘community benefit’ in policy terms. Groups like MABELLEarts aim to create a new kind of artistic experience, one that draws people together to look at things and experience art in their community. I asked Leah Houston, Artistic director for MABELLEarts, how the work she and her team does relates to the notion of public art:

“My hope is that our work is offering new ways to create art in public space; one that is not just physical but uncovers new ways of being together in that space.”

Houston notes that there are many articulations of ‘community arts’, in terms of medium type, but non-artists collaborating with professional artists to create dialogue distinguishes the genre from others. Above all, Houston believes community arts ought to emphasize the importance of the place where collaborating occurs.

Public Art as Socially-Engaged Art

Some traditions of community art align with notions of ‘new genre art’, art created outside of institutional walls where artists directly engage with their audiences and address social and political issues. Importantly, new genre art expands public art to include the ephemeral – something that community arts has in its DNA. Kris Erickson, board chair for MABELLEarts, sees public art in Toronto fixated on the traditional, limiting new ways of conceiving public art:

“Public art as monument misses a lot of the more ephemeral works, and it can be difficult to wrap your head around because you are not necessarily talking about materials, you are talking about putting together a support system for artists to do more long term projects”, remarks Erickson.

Sculptures may provide a public function, but community art takes this one step further by building connections to the area and people around the site, which is why Erickson believes community arts is so vital from a public perspective; “it creates a sense of social inclusion and culture in a broad sense, not just artmaking as commodity.” For artist Darren O’Donnell, artistic director of Mammalian Diving Reflex, a key characteristic of community arts is the focus on process, not outcome: “community arts is not concerned with creating products that are going to compete in the global arts market,” says O’Donnell. By engaging in social issues first, O’Donnell believes that you start from a place that puts people at the centre of the artistic experience:

“In a way, new genre art, and community arts for that matter, is aestheticizing social relations; that is, using social relations as materials by bringing people together who may not ordinarily be together.”

O’Donnell did just that when he joined up with youth in Parkdale to start Young Mammals, a series of projects that helps young people to create art while being mentored by cultural leaders in all aspects of staging a public performance – production, administration, and marketing. Launched in 2011, one goal of the project is for the youth themselves to develop skills to eventually take over the company. The other goal is diversify the arts and culture industries, which O’Donnell says are predominantly white, by giving youth of colour the opportunity to join. Nerupa Somasale was one of those youth, a first generation Canadian, and a core member of the Torontonians – a teen collective within Young Mammals. For her, the opportunity to work with Darren provided a way to address her immigrant experience in Parkdale.

“Growing up, it was a struggle to figure out my own identity, and a lot of new immigrants share that experience. I saw young mammals as an outlet for artistic expression that was of my own accord.”

Along with other members of the collective, Nerupa starred in the short film ‘how to be a brown teen’ – a window into the shared experience of Indian teens wrestling with their parents expectations and new founded Canadian values. Somasale said the film reached audiences in Delhi, but, surprisingly, it was the parents who found it most relatable. Other projects, like Get out of my Room: Toronto at the Gladstone Hotel invited audiences of all ages to experience a day in the life of a ‘hyper teen aesthetic’. Somasale sees public performance as a way to bring adults into the lives of youth in a playful and non-hierarchal fashion:

“the protocol Young Mammals follows is to remove authority, but still give guidance. Never to tell a child to shut up was a rule. A lot of our practice is to foster relationships between young people and adults, to break down the level of authority that exists between us.”

Creating a space for inter-generational dialogue across cultures resonates with Houston and her team at MABELLEarts:

“My work tries to bring together people who would not have the opportunity to meet – young, old, different backgrounds…especially for people who do not always see themselves reflected in the city they live in”

Building strong relationships and communities takes time. Both Houston and O’Donnell have been working in their respective communities for over 10 years. MABELLEarts developed out of a four-year Jumblies theatre residency. Jumblies’ philosophy creates a project in a community with the goal of leaving a legacy behind. The secret ingredient in our work is time, something that others, like urban planners, don’t always have as much of”, remarks Houston.

Expanding the Boundary of Public Art

Supporting public art from development dollars through policy works well for traditional pieces, but community arts organizations are limited in accessing this funding because most policy stipulates work must be permanent. Erickson says that if the lion’s share of public and private funding is going to one type of public art, this limits opportunities to expand the genre:

“If developer money could go to a pool where a certain percentage goes toward form, materials, non-materials, that would great. Combined with matching support from other sources, that would be a big policy win.”

To gain this level of support, Erickson believes that we need to create a bigger conversation about public art in Toronto, and community arts should be front and centre. “There is value to the public in these ephemeral interventions, I think it is crucial to figure out what’s a great way to support that.” Traditional public art should still have a prominent place in the landscape, he adds, but we must recognize the scope of public art expands beyond conventional forms like sculpture to include public art as public space. Houston agrees, and believes community arts has an important role to play:

“I think art has a potential to bring people together across some serious tensions and divisions; there is potential for public art to take that on board more”, Houston remarks.

Creating new expectations about public art can be challenging in Toronto, a City that Houston says feels pressure and responsibility to put something down in the ground. Toronto’s push to show itself to the world through international commissions should not overshadow intangible, local expression: “what gets lost is the small stories that make up Toronto, what it means to live here. That’s the more interesting piece to me, Houston says.”

MabelleARTS has managed to secure a small amount of developer funds (i.e., Section 37) to improve the park, but those are limited to capital expenditures like lighting. In other areas, funding bodies are starting to adapt. O’Donnell says the current move away from discipline-specific funding programs to integrated collaborations across disciplines bodes well for community arts. Partnership grants like Platform A by Toronto Arts Council the Canada Council’s supporting artistic practice and engage and sustain grant programs require artists bring their practice to communities. Beyond funding, Houston believes municipal departments could reorient themselves to address new directions in public art. In Toronto, the parks and culture departments tend to work in silos, not together. For her, the City of Vancouver is an excellent model because parks, culture, and recreation are a joint department, which makes it easier to do art in public spaces, like parks.

Community arts may seem nebulous and hard to pin down; it may not be immediately relatable or obvious. But if public art has no attachment to place – to history and values of a community – it may go unnoticed. Sculptures may attract the public, provoke, and function as landmarks, but community art adds the human dimension. As O’Donnell sees it, the role of public art in a city is inherently social, and community art is a key part of that. If we start by asking, “how do people meet each other” public art can create new ways of being together.

Jeff Biggar works as a freelance consultant, and is currently pursuing a PhD in Planning at the University of Toronto.

The Artful City is a bi-weekly blog series exploring the evolution of public art and its role in the transformation of Toronto, both the city fabric and the community it houses. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org