If the City of Toronto has an evergreen municipal election issue — besides our ritualistic self-flagellation about transit — it has got to be the fate of the Gardiner Expressway.

By my count, the Gardiner thumbs up/thumbs down debate has been in play in every race since 2006, when David Miller advocated the removal the entire central section from Spadina Avenue over to the Don River — an idea first bruited in 1999 by the 2008 Toronto Olympic bid team.

In 2010, Rob Ford used a half-finished Miller-era plan to remove the eastern portion as ammunition in his War-on-the-Car campaign. Four years later, City officials emerged from their Ford-proof bomb shelters with a “hybrid” solution that would partially demolish and partially re-route the eastern portion – a strategy that won backing from (then) candidates John Tory and Olivia Chow.

This past weekend, Jennifer Keesmaat became the latest mayoral aspirant to wade in to this political bayou with an urban design-inflected proposal: pulling down the eastern portion, from Jarvis to the Don, and replacing it with a “grand boulevard” that has the same traffic capacity as the elevated portion. In an interview yesterday, she said she would invest the savings in an LRT serving East Bayfront and ultimately the Portlands beyond.

While Keesmaat’s plan should appeal to progressives and those who rightly believe that sustainable cities have fewer highways, her proposal’s costing had a back-of-the-envelope feel (plus a mistake, about which more in a moment). Her promise also relies on a leap of faith about the power of urban design.

First the numbers:

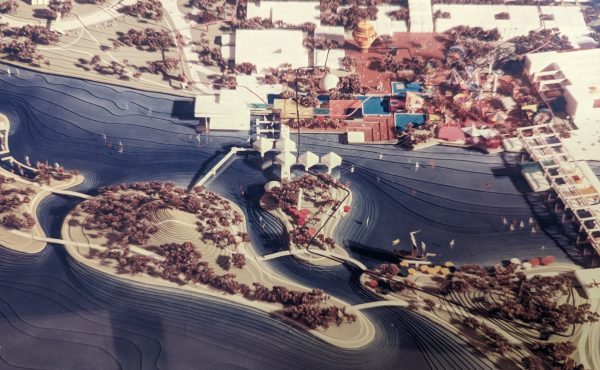

After Tory won in 2014, the City revived the Gardiner East planning process and council landed, after much genuflecting, on a costlier compromise plan than entailed shifting the looping portion of the highway, between Cherry Street and the Don, northwards in order to free up valuable and developable real estate along the north side of the Keating Channel.

This alignment, according to staff reports, would be more expensive for various technical reasons, but would be justified by the return on investment, in terms of re-claiming and repurposing lake-side real estate. Unfortunately, council said yes before the city had sorted out the financials, in particular an anticipated $820 million funding infusion from Ottawa which never materialized.

The current cost is $1.5 billion, according to the 2017-2026 capital budget, all of it funded by the City via debt. Keesmaat’s announcement, however, contends that the new hybrid plan was to cost the City only $1 billion “to prop up part of an aging expressway.”

I’m not a huge fan of gotcha journalism, but half a billion dollars isn’t a rounding error. Nor does her announcement reference the fact that the City in June let a $280 million contract for the first tranche of work — a deal that will be costly to cancel.

She also told me that her contacts in transportation planning have said that removing the elevated portion and constructing a grand boulevard would save about $500 million, which she’d put into a transit fund. Her platform doesn’t include any further costing, such as the potential windfall from property sales – demolishing the elevated portion, she says, would free up 12 acres of land – or reduced maintenance.

Quibbles? Possibly. Such financial matters, as Keesmaat knows from her days as a city official, involve extensive policy work, and depend on often fluid assumptions.

The more serious questions, to my mind, involve planning.

Keesmaat says this new surface boulevard would retain the existing capacity in that corridor, which means it will be a very wide road that runs between the railway embankment and the north-facing walls of whatever gets built in the strip bounded by Jarvis, Cherry, and Queen’s Quay.

Anyone who’s got even a passing familiarity with the waterfront plans knows that the development envisioned for that area puts the tallest buildings north of Queen’s Quay East, which means this grand boulevard will be abutted by a wall of very high towers and will therefore spend much of the day in shadow. There will be virtually no view corridors to the lake, and if there’s a sidewalk, it will face onto a wide road and then the railway embankment.

Keesmaat argues that urban design can address all of these issues – generous sidewalks, a tree canopy, cycling infrastructure, etc. But I’d say a good deal of skepticism is in order. It doesn’t sound like a great place to hang out, especially if there are more pedestrian-friendly corridors – Queen’s Quay itself, the boardwalk, whatever goes up on Quayside — just a few metres south with access to the lake.

Finally, there’s that matter of capacity. A key piece of evidence held up in support of the removal of the eastern portion of the Gardiner is that hardly anyone uses it. Most drivers coming in from the west exit the Gardiner by the time they get to Jarvis, while drivers heading south on the DVP get off at Richmond. Very few people go all the way across.

Yet it’s also possible the lack of traffic is symptomatic of the fact that very few people are currently heading towards that mostly derelict corner of the waterfront. But if we fast-forward a generation, there will be thousands of people living and/or working in that very precinct – on the Unilever site, the Portlands, Quayside, the East Bayfront, and whatever gets built on the north side of the Keating Channel.

Will it be busy? Well, a generation ago, there wasn’t a lot of traffic in what’s now known as South Town. Today, the sidewalks are packed, which is great, but there’s also a ton of traffic, which isn’t.

I’d predict the same for that whole eastern portion of the waterfront. What we see now on Bay or York south of Front is what we’ll see on Cherry, Parliament, Queen’s Quay and Lakeshore.

Given this entirely predictable consequence of new development, I’d say it’s likely that the grand boulevard Keesmaat proposes could be bumper to bumper — an eight-lane vehicle sewer.

Keesmaat rightly notes that in a generation, we will have to be far less vehicle dependent than we are now, and I absolutely agree. But getting there means a great deal more proactive investment in transit than is current taking place, as well as a commensurate reduction in road capacity. A very wide boulevard will induce congestion, and there’s unfortunately no shortage of evidence to prove the point.

So while I generally agree with the aspiration of removing an exceedingly costly downtown highway that few people currently use, I remain concerned the cure may be worse than the disease.

In order to make Keesmaat’s removal/grand boulevard solution work, council and the city’s planners would have to be extraordinarily attentive and disciplined about the way they design both this transportation corridor and development located adjacent to it. Even then, I’d say there’s still a good chance the new boulevard will never amount to much more than a service road skirting the north edge of a neighbourhood that has been purposefully designed to cast its gaze south, towards the lake.

I even find myself wondering if the strip of land under the Gardiner might some day be re-purposed as an eastern leg of the Bentway, perhaps in a future era when there’s enough transit and density in the eastern waterfront that the city realizes it no longer needs Lakeshore in its present form.

Bottom line: by all means, let’s talk about the urban ethics and opportunity costs of plowing such a huge sum into relocating something as antediluvian as an elevated highway. But we must also be clear-eyed and realistic about the unintended consequences of whatever might takes its place.

5 comments

Great piece. Plz. build this:

https://devonostrom.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/green-wave_-proposed-gardiner-plan.pdf

This is planning for the future instead of “same old, same old” we always see. Get on with it!

Have they actually studied use patterns of the eastern Gardiner? I don’t drive, but when I get a ride home from visiting family east of the city to west of Chinatown, they drive me down the DVP, across the Gardiner, and then up Spadina. This route is much faster than trying to drive across Richmond or Bloor. Even on a Sunday night, we encounter plenty of cars doing the DVP to Gardiner ramp and/or coming from the eastern stretch of the Gardiner.

As much as I “enjoy” the lovely boulevard that is Lakeshore amidst its mess of on and off ramps, I can’t imagine any pedestrian wanting to go anywhere near a road linking the 90 km/hr DVP and the 90 km/hr Gardiner. Seems to me like this will just end up being a street-level racecourse that is even less pleasant to cross than the current underpass.

Seriously, maybe we should just reframe the way we think about the elevated highway. The problem isn’t that the structure exists – it’s actually sort of interesting to look at, at least more pleasant than a road full of cars, and honestly, in the tree-less southern tip of town, shade is underrated – perhaps we should focus more on how we use the space beneath it so it’s less of a postapocalyptic dead zone where pedestrians don’t wish to tread.

I thought along the same lines the day this boulevard was announced. With all the new development along this stretch traffic will inevitably increase. And so public transit should be built here in advance to absorb that anticipated new demand. With high quality public transportation available, Gardiner tolls and/or smaller roads will encourage most people to leave their cars at home. If we want to keep the same capacity for cars, in the name of pedestrian safety the road must be buried. Keep cars separated as far as possible from people casually walking around. I think the number of pedestrian accidents on Queen’s Quay speaks for itself, drivers don’t know how to share the road. Regarding funding, I think the city should revisit the idea of tolling the Gardiner, or increase property taxes which are kept artificially low, Torontonians pay less property tax than most other municipalities in and around the GTA.

The Environmental Assessment done jointly by the city and Waterfront Toronto included exhaustive study of all the issues raised and concluded on about every criterion the take-down option was the best. Council’s refusal to act on the highest level of study and expertise was a disgrace. See http://www.gardinereast.ca or go to the Waterfront Toronto Website for all the documents.