Jackie Shane (b. May 15, 1940; d. February 22, 2019) is gone, and this time it’s true. I say ‘this time’ because after Jackie left Toronto in 1971 rumours of her demise abounded. ‘I heard she was murdered.’ ‘I hear she killed herself.’ The rumours persisted for years. Even some of those responsible for the more recent re-discovery and re-appreciation of Jackie frame her story as a murder mystery or horror film.

None of it was true. Jackie moved to Los Angeles and then back home to Nashville to look after her aging, ailing mother. More the dutiful daughter than tragic victim. So the question is, why the rumours in the first place, and why were we so prepared to believe them?

Queer and trans people of colour know the answer. It’s the difficulty we white people have in imagining black and trans lives outside the necropolitical narratives of pathology.

Rest assured this won’t happen in the wake of Jackie’s recent and real death. She made sure of it. In the dozens of interviews she gave over the past two years, Jackie, in her late seventies and larger than life, returned to centre stage to tell her story on her own terms. She was charming, wise, and unapologetic. No pathology here. So how will Jackie be remembered now?

A few weeks before she died, Jackie gave a final interview to Elaine Banks on CBC Radio. Talking about her decision to leave the Jim Crow South and come north, Jackie explained, and not for the first time in words with both geographical and gendered meanings: “One cannot choose where one is born, but you can choose your home.” She went on to say, “I chose Toronto. I love Toronto. I love Canadian people … [They] have been so good to me … We became real lovers.”

It takes nothing away from Jackie’s own experience of Toronto to nevertheless be skeptical about how white Toronto, both queer and straight, might use Jackie’s memories.

I worry that Jackie’s story will be conscripted as historical evidence for what, in the 2018 anthology Marvellous Grounds: Queer of Colour Histories of Toronto (edited by Jin Haritaworn, Ghaida Moussa, and Syrus Marcus Ware), contributor Kusha Dadui aptly names “the new underground railroad.” Just as the old underground railroad has burnished the myth of Canada as a promised land of racial tolerance and acceptance, the new underground railroad promotes the homonational fantasy of Canada as a safe haven for queer refugees and migrants. Come to Canada, where we will love you and be good to you. Except for when we won’t.

In the fall of 1961, a gay gossip columnist for a Toronto tabloid wrote, “Jackie Shane, the sepia songster …is back at the lively Holiday Tavern to the delight of the many fans she established in these parts during her last stint there several months ago.” During Jackie’s run at the Holiday in May, 1961, an LCBO inspector visited the tavern. He noted in his report that “the entertainment was provided by a colored group billed as Frankie Motley Orchestra featuring Jackie Shane. The group sang and played popular arrangements only.” In other words, they played neither too loud nor too black, at least not while the inspector was in the house.

Located at Queen and Bathurst, the Holiday was popular with black residents from the surrounding neighbourhood, and Jackie played there often. The chief inspector for the LCBO noted that “a negro called at my office to complain about being refused service at the Holiday Tavern.” Mr. Leroy W., the complainant, “felt there was discrimination at the Holiday on this occasion and other occasions when he had been in and they would not let him sit where he wanted.”

Jackie, of course, knew this history; she lived it. In 1968, a catty gay tabloid columnist commented, “Jackie Shane isn’t making the scene … as often these days as he (she, it) used to!” As Jackie told the CBC earlier this month, “at first, there were people who are ignorant and talk and talk and don’t know what they’re talking about. They were curious, but when they got to know me … we grew to love to one another.” Jackie added an important caveat: “I loved them first. I had to. I could not allow myself to be angry.” To love first, even in the face of racism and transphobia, was one of Jackie’s survival strategies. To remain angry would have been to burn out and thereby let ignorance win.

My brief sketch of Jackie and the Holiday Tavern are snippets from research I’m doing in the LCBO records at the Archives of Ontario and in the tabloids at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives. This touches on a critical conversation currently underway among queer historians about the status and desirability of the archive. Noting that queer Toronto is “gripped by an outbreak of ‘archive fever,’” the editors of Marvellous Grounds argue that queer and trans people of colour are nonetheless often missing from the archive “as a direct result of policing … of exclusion, erasure, displacement and dispossession.”

Paradoxically, it’s also true that Jackie and many other people of colour turn up in the archives as a result of precisely that same policing, which is to say the over-policing by state agencies (like the LCBO) of the places where people of colour gathered. The tabloids also policed, patrolling the borders of Toronto’s emergent white queer community in the 1960s, racializing and minoritizing its ‘others.’

Resisting these archives, the Marvellous Grounds editors opt for a strategy of “counter-archiving,” a method that refuses induction in “an ever more colourful archive whose foundations remain firmly white.” Freed from archival collection and capture, queer of colour histories tend to be public and mobile.

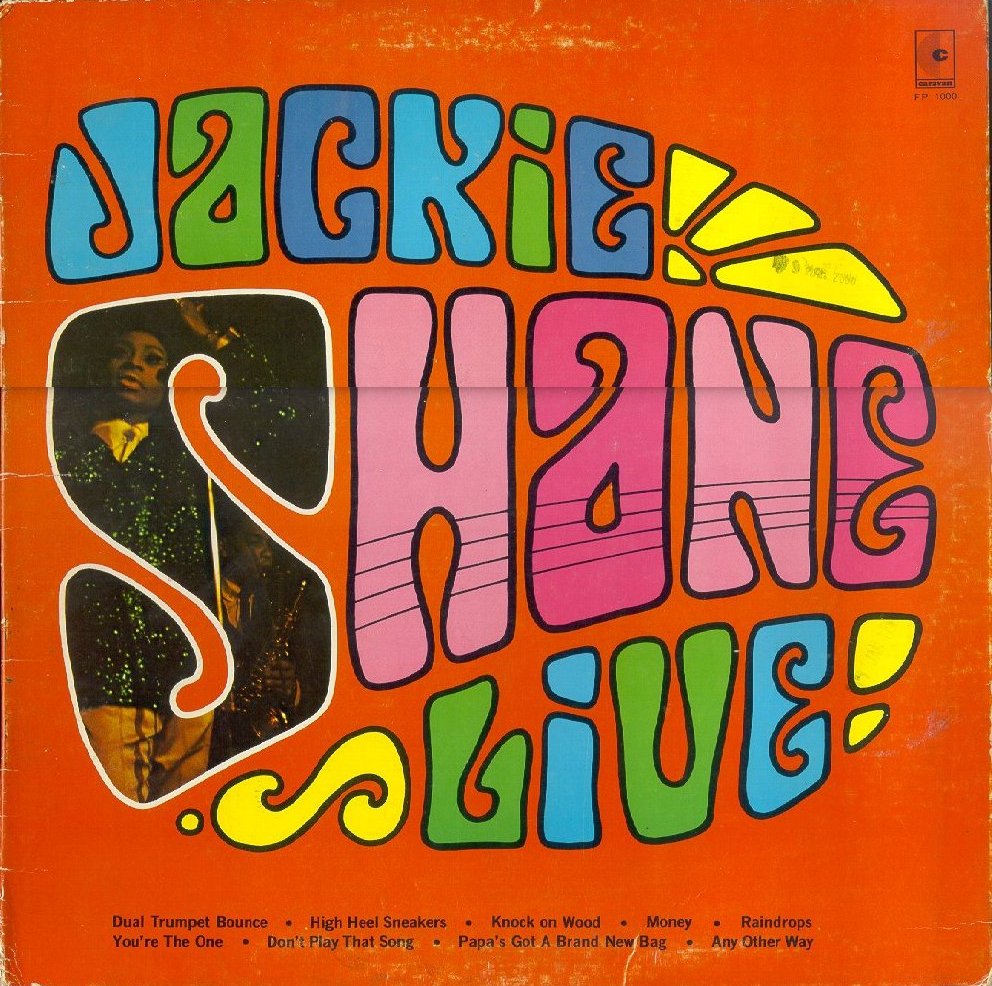

We see something of this in the ongoing Myseum Toronto campaign, which last year plastered Jackie’s story on hoardings across the city and on ad space in TTC vehicles and subway stations. Vintage photos of Jackie flashed by as you rode up and down the Yonge line just as, 50 years before, Jackie worked the Yonge strip as her own ballroom runway. “Miss Shane was walking down Yonge street the other day in full drag,” a March 1963 tabloid reported. “She looked stunning in a beige coat and gray leotards. Her hair was beautifully coiffured and she wore sunglasses.” Jackie strolled “past at just about the time the Ryerson Collegians were finished for the day – I think she timed it.”

To take different example, during last year’s Nuit Blanche in Toronto, Ghanaian-born, London-based artist Harold Offeh curated “Down at the Twilight Zone,” a twelve-hour “living archive” installed on a loading dock. Decked out in homage to Jackie Shane, Offeh and guests such as DJ Nik Red of Blockorama fame, recreated the spirit of the Twilight Zone, the 1980s Toronto club described as “a gay-positive multicultural space … unique for the time and still rare today.”

This locating of history in urban space helps to make sense of why, as the editors explain, “Marvellous Grounds began as a mapping rather than archiving project.” However, it quickly became clear that there is “an unmistakable desire in QTBIPOC communities for history and lineage. Younger folks in the city crave elders, who are missing and dismissed from a white archive that passes itself off as ‘the queer history.’” To those younger folks, Jackie Shane awaits you.

For us white folks, I hear Jackie’s story not as an endorsement of the new underground railroad and white Canadian benevolence, but rather as an historical and archival call to action. We’ve no right to ask Jackie to bear her pain and anger for the benefit of our education. Instead, it is the responsibility of white queer historians to enter the archive and uncover our anti-black / anti-trans histories, and to own them. It is long past time for us to turn white archive fever into productive anger about the white archive.

Active in the Toronto queer movement for many years, Steven Maynard now lives in Kingston, where he teaches the history of sexuality at Queen’s University. He wrote the introduction, about Jackie Shane, to Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer, edited by Stephanie Chambers et al. (Coach House Books, 2017).