Chicken Little, it would appear, has left the neighbourhood. In an 18-7 vote, city council yesterday approved the development of four-plexes as of right in all residential neighbourhoods, especially those that had been set aside — basically since their construction in the post-war decades — for detached and single family dwellings.

The winning side comprised not just progressives, including those who have in the past expressed scepticism about missing-middle housing, but also staunch, ward-heeling conservatives, like Frances Nunziata, Michael Thompson, and Nick Mantas. The debate was refreshingly free of snide asides about market urbanists, and council succeeded in resisting the ever-present temptation to bleed an idea dry with a thousand small cuts — pilot projects, studies, and other entirely phoney delays.

The principle at the core of the new policy couldn’t be more anathema to the way Toronto has been managing its own land use for literally decades, with one notable exception which I’ll get to in a moment. By adopting an “as-of-right” approach — and then dispensing with technical IEDs like limits on floor-space indexes or unreasonable height restrictions — the planning department is executing a 180-degree pivot. We are moving away from a fundamentally restrictive zoning regime (itemized rights) to one that is far more permissive. Negative freedoms in exchange for positive freedoms.

The asterisk here is that council’s single most successful and daring zoning move in recent memory took place in the mid-1990s, prior to amalgamation, when the old City of Toronto adopted the so-called “Kings” policy. At the time, dozens of older warehouse buildings in the King East and King West areas were threatened with demolition because their manufacturing tenants had moved away.

But those half-vacant buildings had attracted many `illegal’ uses — artists’ lofts, start-ups, non-profits. Council at the time passed a bylaw that removed the strict land use designations from those areas — i.e., manufacturing — and instead legalized whatever happened to be going on in those buildings. That rare instance of regulatory risk-taking — backed by then mayor Barbara Hall, on the advice of Jane Jacobs and Ken Greenberg, with Paul Bedford in the chief planner’s chair — laid the groundwork for the revitalization and intensification of Toronto’s half-derelict industrial zones.

What is the learning? First, that interesting things happen when the planning department takes a big step backwards. Second, that there’s enormous value — not just financial, but social and environmental — in the act of allowing the city to act like a city.

Which is to say, recognizing that entrepreneurial activity is a feature, not a bug, and shouldn’t be quashed. One need only look at the largely non-conforming commercial re-uses of the ground floor apartments of many of Montreal’s post-war walk-ups to understand why it’s important for municipalities to be a little less fixated on their own rules.

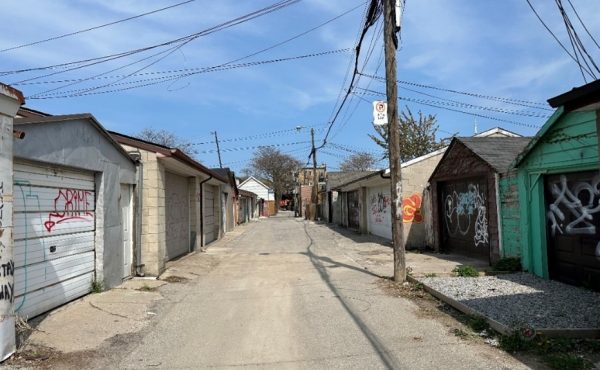

How do these ideas apply in low-density house neighbourhoods? First of all, we know that the Yellowbelt isn’t just a sea of single-family homes. Long before the city got around to acknowledging secondary suites, there were thousands of illegal basement apartments, rooming houses and other non-conforming uses in those neighbourhoods. It’s safe to assume that the work-from-home era has also given rise to all sorts of quasi-tolerated commercial activity (home offices are fine, but only if customers or clients don’t visit).

In the old City of Toronto, neighbourhood stores functioned in complete harmony with the surrounding communities, deemed for planning purposes to be “legal non-conforming.” Amazingly, it was only last year that council agreed that such small-scale businesses which hadn’t been grandfathered in place were, well, okay. And not just okay, but valuable and valued.

The multiplex decision is a long-overdue step in allowing the city to do what it wants to do. Planning consultants like Sean Galbraith are acutely aware of the fact that homeowners and small-scale builders have been trying to push this envelope for years, only to run into the triple whammy of resident association obstructionism, rigid zoning and political opportunism.

We need to be realistic about what this policy shift will and won’t do. The latter first: it won’t provide the enormous amount of affordable rental housing that Toronto needs, and council as well as the next mayor need to make that job one in the years to come. But the multiplex reforms will begin the long hard task of reversing population decline in the city’s far-flung neighhourhoods. That densification — which will almost certainly spread to other GTA municipalities — will work against sprawl and make better use of municipal infrastructure.

It will also kick-start a cottage industry of small-scale developers, designers and clients who will bring their own ideas and capital to a table that has long been reserved for the big-name builders, their financial backers and the commercial brokers that fill the podiums of their condo towers with crappy chains.

I do, however, want to add a note of caution: the city and the planning department in particular very much needs to learn from past mistakes in order to ensure that this shift succeeds. Which means: no design guidelines, additional staff resources directed towards enabling, as opposed to obstructing, these applications, and plenty of tolerance for off-beat projects that don’t exactly meet the letter of the bylaw.

And here’s the most important take-away: the sky will not fall, just like it didn’t fall when artists began turning industrial lofts into apartments, or when homeowners quietly began to rent out their basements to help with their mortgage payments, or when the accountant who lives two doors down began seeing clients in her dining room.

As of right means letting the city be a city, finally.

One comment

People who pay top dollar for a nice neighborhood of single houses will see a downgrading. This will bring down the value of what they own. Will they get their property taxes reduced?

I lived in an R-1 residental neighborhood in Islington made up of all single residences. You could not even park your car overnight in your driveway if any part was beyond the front line of your house. I had to park inside the garage which was in line with front wall. Fine with me. Furthermore NO commercial vehicles of anykind were allowed to be parked anywhere. All of this kept us a nice neighbourhood.