The Creekside Community Centre was packed on Thursday Evening, bustling with conversations between city staff and residents as they observed the Viaducts Proposal. Boards [PDFs] showing the newly minted concept are the latest development of the Eastern Core Planning Strategy and the Northeast False Creek High Level Review. One of the more recent inputs has been the Re:CONNECT competition, which gave opportunities to inject outside ideas and new strategies to help guide and inform these upcoming planning processes, by asking the leading question: “Is this the best we can do?”. It let the City avoid the risk of politicizing “whacky” ideas, as removing the Viaducts was seen as for some sometime leading up to today. It seems to have been a worthy gamble, and from my view the new product is worth the trouble.

This was the Second of three open houses for the newly released Concept Vision of the Viaducts produced in coordination between the City of Vancouver, Perkins+Will—prolific local urban design firm—and Phillips Farevaag Smallenberg—well-respected local landscape architects. The last is open house is today, Saturday the 9th, 10am -2pm at the Central Branch, Vancouver Public Library. However, there is also still time look at the boards and engage the city with comments online.

The design concept attempts to rationally remove the Viaducts by moving an expanded two-way Pacific Boulevard to the North side of the SkyTrain alignment and connecting to Prior Street. It also ramps down Georgia Street from Beatty to connect to the boulevard system at that lower level.

The centre of the site is presented as a large park space that integrates the existing green spaces to a renewed False Creek beach waterfront. Development on either side becomes a contiguous whole, connecting the towers of Concord Pacific around the Stadiums into International Village and patching up Main Street with a high-density public “Hogan’s Alley” mixed-use mid-rise development on the two blocks currently used as the Viaducts’ on-ramp.

Why is this site so important?

Simply put, there are three major elements on why I think this site and its redevelopment is so important to the City.

1) This district –along with the False Creek Flats– is the last significant part of the City’s old industrial Core that has yet to be planned for redevelopment. This will be the last of the great mega-projects that have defined Vancouver’s urban nature since after Expo86. A bar for sustainable thinking in urban design has been set in Southeast False Creek, the project before this, and what ever happens on this site is likely expected to surpass that vision.

2) This place has a strong history with terms of politics, change and what being a city means. It was the fights against the freeways, here, that was the proving ground for many of Vancouver’s now older generation of progressive politicians. Young advocates, working with and as representatives for the Chinatown and Strathcona communities, honed their skills battling to stop the freeway at this location.

The viaducts were to be one part of a multi-wing system, yet still stand as the monument to that group’s success by being their only loss. Having no urban freeway is considered by many to be the defining element that makes Vancouver’s core neighbourhoods livable, vibrant, and urbane. As Gordon Price says, “it is the greatest thing that never happened”, yet this site still stands out as an anti-urban lost space, particularly in the overpowering relic of infrastructure left on the site.

3) This site has been the dividing wound at the crux between its seven surrounding neighbourhoods, all of which connect to each other at this juncture of the City’s core. Strathcona, Chinatown, GasTown, False Creek North, Southeast False Creek, the Eastern Flats and the Central Business District all have vested interests in—and potential impacts on— how this site is planned and redevelops. Without urban repair, all seven have struggled to work as a connected system of district neighbourhoods and a number have been literally divided by the infrastructure and emptiness of the site.

A heritage of Viaducts:

As highlighted in Spacing Vancouver’s in-depth 3-part series last year that examined the history and issues of the Viaducts, there is a long tradition of viaducts flying over these northern shores of False Creek. There was the Georgia-Harris Viaduct that as early as 1915 crossed over the rail tracks, barge slips, and belching industry of the Creek. By the late 1960s Vancouver was desperately trying to catch up with the rest of metropolitan North America to fully integrate and modernize the city for the car. The viaducts as we know them were the only successfully installed pieces of a downtown interconnecting freeway system that would have cut through East Vancouver, Chinatown, Gastown, and even Kitsilano.

The threat of demolition of Vancouver’s ethnic and historical neighbourhoods—and the actual demolition of the Vancouver’s only Black enclave of Hogan’s Alley—proved to be the last straw. Learning from Freeway revolts in other cities —as exemplified in the battles of Jane Jacobs among many—a new wave of urban understanding, public energy, and populist politics blocked any further expansion to the system from the early 1970s onward.

I have had a focused interest in this urban redevelopment site since my first year of college. As part of an urban geography class that eventually led me down the path to planning and urban design as a career, I studied the structure, history, and urban morphology of the then fallow and desolate Northeast False Creek.

At the time, it had not transitioned from its post Expo86 existence as a razed parking lot. It still holds that lack of function, but little more than a decade ago, few could see the site’s potential beyond the Molson Indy Track that twisted around the macadam and underneath the concrete pillars of Vancouver’s only successfully installed piece of freeway infrastructure.

Re:CONNECT Viaducts:

The Re:CONNECT Competition had no clear winner, but there were a number of strong Ideas that came out of it. More than half of the competition entrants showed some sort of elevated green space as part of reuse of the infrastructure –á la NY’s High Line– but others looked at removal rather than reuse, and these seem to have sparked the interest of the Planning Department.

In particular the –Viaducts=Park+ proposal made by a cooperation of Larry Beasley, Jim Green, Dialog, and PWL seems to have provided the rationalizing idea necessary to make a concrete proposal for the removal of all that concrete. Its “bold new concept” to move traffic to the North Side of the SkyTrain guideway in a grand boulevard was reminiscent of the Cheonggyecheon in Seoul and Embarcadero in San Francisco. In a similar move, the Downtown is connected to this boulevard via a ramped down Georgia Street, which would then terminate at False Creek, thereby allowing it to be an integral part of the renewed network below.

Despite being my favorite proposal, certain problematic issues still existed. Specifically, it proposed an interesting and commendable building type of wide sloping towers with green roofs, but placed them in a row equivalently blocking the northern from southern sections of the site and dividing neighbouring districts, in the way that the Viaducts did.

In a similar, well-intentioned fashion, some of the “Park” concept went too far. Vancouver, and False Creek in particular, has an abundance of green spaces. What is often lacking is effective programming for many these spaces. Where the on-ramp sections of the Viaduct currently divide Main Street, the entrants proposed a Park Space that would connect into Strathcona. Although this park would retain the wound of the Hogan’s Alley demolition, it would also maintain a conceptual barrier separating the North and South sides of Main Street. Extensive and ill-defined spaces, would also be hard to program despite providing effective urban habitat. It is the challenge still facing in the newest proposal.

Structural Elements of the New Vision:

The proposed concept plan has a number of strong elements that seem to be simple answers to the design problem that planners and designers have struggled with for decades. The general overview of the design seems to function as an agglomeration of a number of previous thoughts and principles brought forward in the several past planning processes and concepts.

Reconnecting Urban Fabric and Streets:

The design proposal focuses on the sloped Georgia Street terminus that connects to a renewed multiway Pacific Boulevard on the northern side of the SkyTrain guideway. The new boulevard connects other streets and pedestrian paths through the sites with intersections and at-grade crossings. A streetcar alignment—approved in the 2005 Downtown Transportation Plan—is also included and runs to the south side of the new boulevard.

Georgia Street’s descent from the escarpment allows the ceremonial street to run from “water to water” with a marking fountain at its end to match that of Lost Lagoon. There have been a number of proposals over the years for a “Georgia Steps” that would act as both pedestrian access and public space in the sun. With the removal of the Viaducts, this plan continues that thinking, but also adds a High Line-like remnant to connect both sides of the Rogers Arena with an elevated public space.

A new shorter elevated cycling ramp climbs up to this Space, crossing over Abbott and the SkyTrain at Stadium to connect to the Dunsmuir separated bike lane.

One of the few elements in the design that makes a significant alteration without changing the use is a re-alignment and removal of the s-curve of Carrall Street. The change make the design more rational in plan, but also seems to remove it as a vehicular connection. If the rights-of-way are carefully managed, this could be a strong way to make a strong north-south park spine, but there is a risk it could lead to a street grid that continues to divide the neighbourhoods.

Nonetheless, the central theme of this plan—from the boards and the design actions—is connections. Pedestrian movement is clear in the plan and appears to be supported by other modes. Connectivity between buildings and between spaces are considered as much as connections between major elements of the road network.

A Grand Waterfront Park:

The central defining use in the proposal is a grand Park that incorporates Andy Livingstone Park and Creekside Park, and centres both of them into a central urban Waterfront Park. A green space at the eastern end of the concord site has been in the books since the 1980s. “Capping” sites with a park was deemed the easier, cheaper, and safer way than remediating those soils below the site that were made toxic by the industrial activity there over the previous century.

This large park draws public space from the shore—shown with public piers and beaches—deep into the urban fabric. Enough so, that it feels to have a direct boundary along, or direct connection into, each of the seven surrounding neighbourhoods.

As mentioned earlier, one of the risks of a park of this size will be the difficulty in developing activity programming and interest in its spaces. The design has focused a set of “rooms” extending from the central Carrall Street spine, where different active and passive programming spaces can be experienced as independent moments and distinct elements of the park. The park is still large, however, so it will take skill to organize it in such a way that people develop a sense of value towards the place. The newly created urban farm under the viaduct could potentially have new life with a permanent home in the more marginal expanses of this green space.

New Land – New Developments:

The concept plan also clusters together new development areas at the edges of the plan, where neighbouring development types are utilized and extended. This might be seen as both a critique and commendation. There are few surprises here, save for the lack of something new or bold, beyond the re-oriented fabric of the area.

To the west of the Park, a continuation of Vancouverist podium towers wrapping around the stadium. These are buildings we have come to expect from the north shore of False Creek. Aside from the removal of the viaducts, little has been done to alter the recommendations from the North-East False Creek High Level Review, ultimately allowing more room to fit more of these types of high-rise developments.

Conceptually, it completes the Concord Pacific site as a single developed and imageable whole. It pushes no new boundaries, but seems to be the developer’s ‘sugar’—giving Concord relatively ‘safe’ and sellable building types—to take with the ‘medicine’ of the drastic shift to the ground-plane and and still to be negotiated investment in amenities.

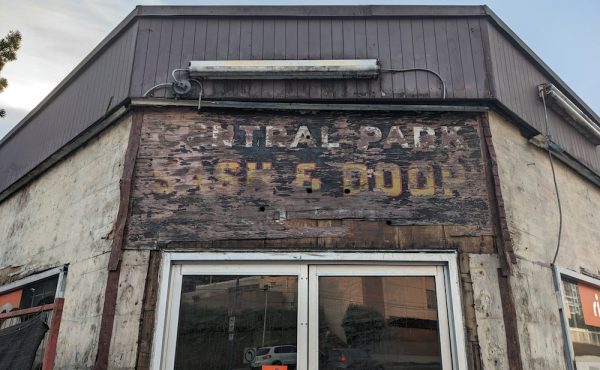

On the eastern side of the Park is a renewed Hogan’s Alley. The two blocks of the on-ramp to the Viaducts are returned to be building parcels that relatively match the surrounding density of their neighbouring blocks. The cluster of mid-rise buildings and squat towers helps to repair main street by continuing activity along it and hold one or two pleasant surprises.

For example, in reaction to the original Hogan’s Alley neighbourhood that was destroyed by the Viaducts’ construction, the new proposal incorporates a retail lane that increases pedestrian and cultural connections. The vibrancy in this mixed-use lane proposal evokes active retail lanes pedestrian market developments not found much in Canada, but increasingly successful in Australia and Europe. There could be some very interesting and creative development opportunities by respecting the site’s past and responding to the traditional structures that make Chinatown so unique.

A Dead ‘Simple’ and Elegant Solution:

When a solution to a complicated problem seems simple, even too easy, it is the best praise that a designer can give. It means the idea will probably work, that there is elegance to the plan, and that many actors –once seeing it– might likely come to a similar conclusion. Big hurdles of design logic must be, and were, traversed to get to this stage.

Now is the time when the proposal is being brought to the public. Those at the meeting seemed to react to the designs with positive trepidation, as they appreciated the overall thought of integrated and completed neighbourhoods, but still needed to be eased into the idea that removing such an large piece of infrastructure won’t lead to traffic nightmares or “ruin” their adjacent communities. Engineers were doing their best to show that even the conservative estimates, where no increased rate of transit usage was registered, showed that the single boulevard road would function well where four one-way streets did previously.

The path of planning is still fraught with peril, as implementing the concepts, and negotiating with stakeholders will define the next stages. The troubles of the Olympic Village show where politics, markets, and marketing, can trample a path towards success. This is not an Official Development Plan; it is a concept… and concepts by nature are there to inspire conversation about what can and should happen.

Yet, a good and tangible set of planning ideas do shine through, and my hope is the next stages will further elegantly massage it into realizable and naturally vibrant place that we will all share with pride as Vancouverites.

***

Brendan Hurley is a local urban designer who focuses on planning for adaptive neighbourhood change. His recent work has been internationally focused, but is strongly rooted in his native Vancouver. Living and working out of the heart of downtown, he remains keenly focused on the region’s development and history. Brendan is a regular contributor to Spacing Vancouver, but also consults as director of the UrbanCondition design collective.

6 comments

The big loser in this equation is Strathcona.

Despite the promise of long-awaited traffic calming on Prior/Venables when Geoff Meggs first pitched his legacy project to the Strathcona residents for our early support — the open house reveals the new six lane Pacific/Expo highway as collector for west Georgia traffic, and then linking to Main Street and on to Prior as the new “direct east-west link to the downtown for commuter vehicles and large goods movement trucks” ; this on a neighbouhood collector street functioning as a major arterial route that bisects the neighbourhood and separates us from our park.

To add insult to injury the City has shamelessly exploited the community’s historic struggle against a freeway to justify the viaduct removal, while putting a freeway through the community. From Geoff Meggs own website:

“It’s an important victory for community organizations like the Vancouver Chinatown Revitalization Committee and the Strathcona Residents Association who spoke out strongly in support of the staff recommendation.”

To be clear, the residents of Strathcona spoke in favour of viaduct removal in conjuntion with Prior Street traffic calming, not in lieu of.

Staff assure us that the connection of a new six lane highway AND Main street to Prior will “in a worst case scenario” have a neutral effect – which frankly I find quite incredulous.

Vague, maybe-someday mention of a Malkin route are not good enough. Traffic calming on Prior needs to be part of this proposal.

The prior commentator of Strathcona brings up a very real concern about the increased traffic flow through his neighbourhood. Well at least his neighbourhood gets recognized in Hurley’s article. There are some 4,000 residents living in Citygate, hemmed in by Terminal and Prior Streets and Quebec and Main, that didn’t even merit a mention. Heck, if you look at the first concept plan directly below the title, not only have the viaducts been removed, but apparently so have all the present Citygate towers along Quebec south to Science World. The Citygate residents, who by the way, have been very proactive in trying to get the City and the developers to finally do something about this NE corner of False Creek, are also concerned about increased traffic congestion along Quebec which is six lanes already in places. Aside from the traffic issues, there is also no real timeline for any of this to actually be finished. It’s been over 20 years that Creekside Park has been promised and will still in all likelihood not be seen for another decade or two, and yet the towers keep going up.

In brief response to your comments:

John: Strathcona is a ‘Neighbourhood’, but I would have to argue that the 3 blocks of Citygate is only a ‘Development’. Unfortunately it has always been a bridging development waiting for other neighbourhoods to develop around it. It may even take some time for enough development to meet the site for Citygate to be able to effectively adopt an identity of such neighbouring communities. But for now the towers sit like an Island of development on their own, simultaneously characterized by False Creek and Main Street. My feeling is that the buildout of South East False Creek to and eventually across Main St. will provide a context for your home to fit as part of a neighbourhood. The Hogan’s Alley development could likely be another anchoring improvement with a transitioning height and character between that of Chinatown and the Citygate towers. However, as you adressed, the timelines are still to be worked out.

Pete: You bring up some valid concerns. Having lived next to Prior on Hawks Ave I have personally felt the division that the traffic makes, effectively isolating Strathcona Park from its eponymous neighbourhood. I know as someone who has driven that route in all of its permutations that one of the Main problems for Prior is the amount of traffic that directly and with few options cross the site, not to mention the speeds at which they do so. An At-Grade avenue that is crossable by pedestrians (even an arterial like Kingsway), despite width does not constitute a “Freeway” betrayal. While a Malkin St Diversion option feels far flung, I can say that because the flows are all in the same at-grade system, the higher impacts will probably be felt on Main and Quebec Streets, which currently has less direct options to access and exit the Downtown. Terminal Ave is still the preferred route by many, even without the ease of access options.

Unfortunately both the Flats and Viaduct processes need each other to make options clearer. The best I can say is to keep fighting for what you think is needed in your neighbourhood, and show how the options provided can be utilized or altered to attain those goals.

Great piece Brendan! Well researched and balanced presentation.

It seems too late in the day of North American Modernism to propose yet another “Towers in the Park” scheme. Supprters of a more progressive Vancouver urbanism—including the ones that fought Freeway Fight, evitalized Gastown, denounce building towers in Chinatown, would like to see Japantown brought back, and the whole DEOD failed experiment dealt with through a neighbourhood strategy, rather than ghettoizing policy—are seeing right through this scheme.

There is really nothing to like here, where the greatest expense is going for moving and rebuilding roads (is that REALLY necessary?), the pandering to the Condo Kings brazen, and the commodification of Hogan’s Alley as a-historic as what has become of Shanghai Alley.

Build the Malkin overpass first. I believe that the oldest neighborhood in Vancouver has taken enough beatings with traffic running through such a beautiful community. Help preserve Vancouver’s heritage and slow traffic down on Prior. How many people and pets have been killed on Prior St? Malkin and National Ave have alot less to no homes on them. Use that space for traffic flow.

If the people making the decisions to how the traffic should flow have any connection to Vancouver… they will save Strathcona from being divided into two.

Regards

Vince 604-762-1103

This is a thoughtful piece, Brendan. Thanks for approaching it with both a wide-angle and a narrow view. I have to say that I’m far from sold on the package. I’ll give three shortcomings by way of examples, though there are more.

First, there’s the business of “patching up” or “repairing” or “renewing” and “reconnecting” Main Street. Notwithstanding the quality of the City’s vision for what was Hogan’s Alley (only on one side, mind … on the other side of Main it was industrial and commercial), it’s only a vision. The City doesn’t build developments, developers do. And a developer may well propose two 84-storey blockhouses (of course they won’t, but you take my point — the current drawings are just “artist’s impressions” and you can’t take those to the bank). No, the real point is that the ‘reconnection’ is implausible: there’s nothing to “reconnect” (the Cobalt and the power substation?!?) and there’s going to be a six-lane motorway alongside the project, which will act more like a moat than a bridge.

Second, and this relates to the first, is the notion that the project will somehow “repair” something in the basin that was damaged by the Viaducts. There’s nothing to repair. It was an industrial, Stygian pit with some sketchy moorages before the Viaducts, not a leafy neighbourhood or a waterfront of charming vistas and colourful personalities. There was a gas plant there which, to my mind, says it all. The area under study has always been one of the grimmest sections of the city and suggestions that getting rid of the Viaducts allows us to set things to rights misrepresents the truth.

Third, there’s the hidden-in-plain-view ethos of the project which is both highly ironic and very dangerous. In the ’50s and ’60s, the mantra was automobilism: independence, movement, expansion to the suburbs, consumption of cars and gasoline, speed, comfort, and an iconic artifact of household achievement (viz.: a Buick). In this century, the touchstone is housing: condos, towers, affordability, renewed urbanism. Just as the enthusiasm for freeways blinded planners, politicians, and voters to the damage that could be inflicted on neighbourhoods and quality of life in the city, so too the cult of the condo and greenspaces is moving forward without much regard for the broader social and economic health of the city. In the name of more towers (and ask Concord Pacific how they feel about that parkland…), we’re being asked to get out of the way of Progress. Again.

Warmly,

John.