Author: Eve Lazarus (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017)

In recent years, Vancouver has enjoyed a renaissance of histories exploring the city’s seedy underbelly—gangsters, bootleggers, nightclub owners, and corrupt police officers. While researching a murder for her last contribution to this genre, Cold Case Vancouver (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015), Eve Lazarus first encountered pioneering forensic scientist, John F.C.B. Vance and wondered why “good guys like… Vance,” whose tireless efforts helped solve countless missing persons cases, hit-and-runs, murders, and run-of-the-mill crimes in Vancouver and across B.C. and Yukon, seemed “to be unfairly passed over by history” (198). So she started digging further into Vance’s story, tracking down Vance’s grandchildren, who still had boxes containing his personal journals, case notes, news clippings, photos, and even bits of evidence he retained after retiring in 1949.

The result of her research, Blood, Sweat, and Fear, is a captivating read which uses Vance’s life and work as the narrative thread weaving together accounts of more than a dozen cases he worked on during his 42-year career. First employed by the city to test the water supply, milk, and food for public health, Vance got his first taste of police investigation in 1914, when he was asked to determine if a stain found at the scene in a missing persons case was human blood. In time, more and more of his time was dedicated to police work. By the 1930s, news of how his forensic work and courtroom testimony helped catch and convict—or exonerate—culprits filled newspaper pages. Dubbed the “Sherlock Holmes of Canada” (9), he was the subject of feature articles in national magazines, and was so feared by local criminals that, in one year alone, there were seven attempts on Vance’s life.

Detailing the quiet and dutiful scientist’s standard procedure, Lazarus walks the reader through his careful examination of crime scenes. As she describes his collection of shards of broken glass, discarded cigarettes, or ripped fragments of cloth for analysis back at the lab, at times Blood, Sweat, and Fear reads like a page-turning whodunit, as the reader tries to guess which piece of evidence in a given case will prove to be the proverbial smoking gun. The book is a brisk, entertaining read about a fascinating character.

In selecting incidents from Vance’s case files, Lazarus moves beyond blood-and-guts sensationalism of some true crime. As in her earlier books, she shows a knack for humanizing victims and perpetrators alike by giving readers a sense of who they were and how their actions—and the implications of their crimes—were sometimes shaped by larger social forces. She links, for instance, the difficult adjustment of soldiers returning home from the Second World War to the rise of youth gangs in the mid-1940s; and explores how a series of suspicious deaths at an unlicensed hospital in Japantown were reported quite differently by the city’s mainstream press and its Japanese-language newspapers.

Lazarus gives the reader a sense of Vancouver in its formative decades, right down to recreating Vance’s streetcar commute along Granville Street and Hastings Street. And, shining another light on the corruption that pervaded the city, Blood, Sweat, and Fear features reappearances of some individuals from Lazarus’ previous books, including John Cameron, the on-the-take chief of police, and his gangster buddy Joe Celona, among others.

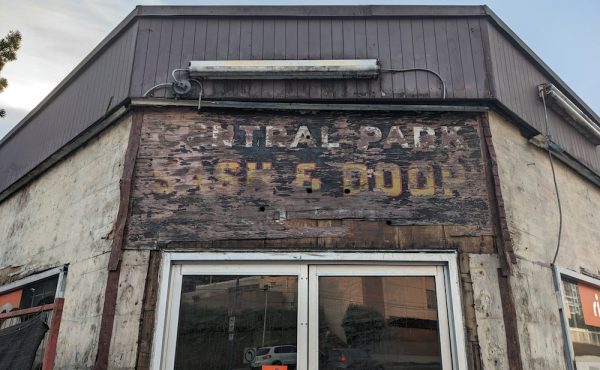

There are, however, one or two moments when something stated matter-of-factly begs for some additional explanatory context–particularly in relation to the late 1920s and early 1930s, a less-documented period of Vance’s life when he became increasingly focused on police work but he was not yet a mainstay in the newspaper headlines. It would be great to know more about municipal politics and the debates for and against the city’s decision in 1932 to build Vance a large, state of the art laboratory (at 240 East Cordova Street—now home to the Vancouver Police Museum, which will host the official book launch of Blood, Sweat, and Fear on June 8).

By that point in time, Vance had contributed to solving any number of cases, but few other law enforcement agencies were then investing in forensic science. Who pushed for the city to make the investment, and who resisted? Did Police Chief Charles Edgett’s ouster from the department in 1933 have anything to do with his support for Vance’s work? Certainly, there were some in Vancouver who thought it sufficient for police to rely upon the circumstantial evidence to secure convictions rather than suffer the expense of Vance’s forensics work. Mayor L.D. Taylor said as much in 1934 when Vance asked for a pay raise. “Long before we had such a branch,” Taylor expressed skepticism of Vance’s contributions, “the police were obtaining convictions against criminals just the same as they are now.” (94).

The absence of this context is noticeable mostly because Lazarus’ coverage of the internecine office politics within the department Vance experienced in the mid-1930s—as the petty jealousies of detectives and active resistance of top brass reached a boiling point—is the biggest strength of Blood, Sweat, and Fear. Calling upon Vance’s personal journals, Lazarus articulates his inner thoughts and suspicions, as well as his interactions with his allies and his rivals. Because officials knew to express support for the forensic investigator in public, access to Vance’s personal papers allow Lazarus to take us beyond-the-headlines to see how one of the “good guys” navigated a system rife with corruption. And, ultimately, it is this fresh perspective, throughout the book, that elevates Blood, Sweat, and Fears from the local history crowd.

***

For more information on Blood, Sweat, and Fear, visit the Arsenal Pulp Press website.

**

Kevin Plummer has written on local history for the last decade. For much of that time, he was co-author of Historicist, a National Magazine Award-winning weekly column exploring Toronto’s past at Torontoist.com. Most recently he contributed to Spacing’s just published Toronto Public Etiquette Guide by Dylan Reid.