Author: Matt Hern (MIT Press, 2017)

Book Reviewers: William Dunn & Claire Adams

Portland is a liveable, progressive, and hip city. It’s also incredibly white. As Matt Hern illustrates in What a City is For: Remaking the Politics of Displacement, this is the case because “the black community was destabilized by a systematic process of private-sector disinvestment and public sector neglect”.

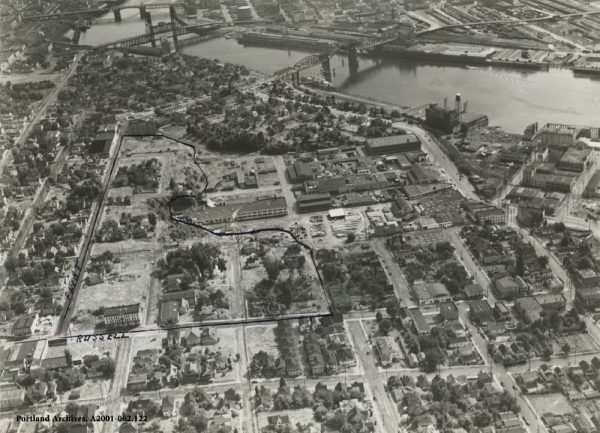

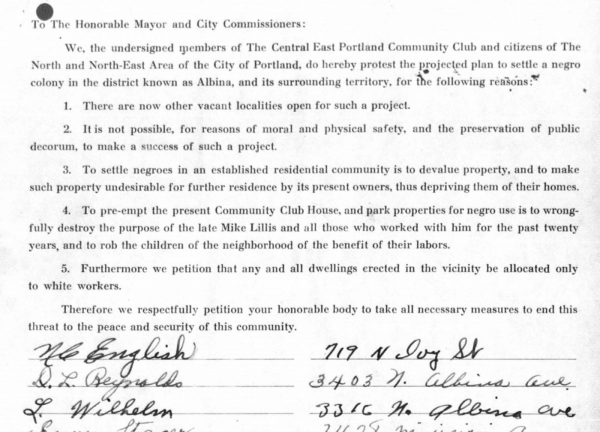

The roots of this destabilization are situated in Oregon’s explicit history of legislative racism, which Walidah Imarisha, who Hern interviews, describes as “an attempt to create a white homeland”. This racism has manifested at the city-level through Portland’s continued displacement of its black community, who arrived en masse in 1948 when the neighbouring city of Vanport flooded. Portland’s local politicians, real estate board, existing residents and banks, worked together to ensure that Portland’s newest community was only able to settle in one neighbourhood, Albina, in the Northeast of the city. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, less and less public and private capital was invested in Albina, resulting in severe neighbourhood decline. Karen Gibson, in her article ‘Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940–2000’, writes: “The real estate industry (government housing officials, Realtors, bankers, appraisers, and landlords), by denying access to conventional mortgage loans, played a pivotal role in perpetuating the absentee ownership and predatory lending practices that fueled the decline in housing conditions. Many Black residents were denied the opportunity to own homes when they were affordable.”

By the early 1990s, this disinvestment had attracted the attention of speculators who, noting the increasing cost of land in other parts of Portland, snapped up the cheaper property in Albina. This kick-started what has been identified as a typical pattern of gentrification: The cheaply bought properties were redeveloped as housing for higher-income earners than those who at that time lived in Albina; land values in the neighbourhood increased generally; and the original residents weren’t able to keep up with rising rents let alone afford to purchase any of the newly built dwellings.

Hern ties this process to the displacement of Albina’s black population, noting that the neighbourhood was 75 percent black in 1990, but less than 25 percent black by 2010. Albina community activist Joice Taylor explains: “Now there is no minority neighbourhood in the city: and that was intended! They created this! Now you don’t see anything to distinguish one neighbourhood from the next. It’s all the same.”

What a City is For isn’t really only about Albina though. Hern uses Albina’s story, a story replicated in one way or another in cities across North America, to set-up his central question: “Who deserves access to land, and why?”. While noting that the literature on gentrification is helpful to understand the process of displacement, Hern asserts action toward change must be “rooted in an aggressively equitable and decolonized politics of land, ownership, and sovereignty” and that the city is “the right place to start that project, not as a metaphor but as a material rethinking, reimagining, and reallocation of land.”

In North America, the ownership and commodification of land followed colonialism. As a longtime Vancouver resident, Hern is keenly aware that inequities here are a result of the dispossession of Indigenous peoples. He highlights the hypocrisy of defending private property rights on stolen land:

“If the state insists on the inviolability of property (i.e., I cannot come and take something of yours because I want it; that’s theft), then how valid is all our property law (and thus all our law) if it rests on a collective and continuous violation of its own basic precept?”

Referring to the ownership model, the dominant view of property which claims that there are only two types—collective and private—Hern makes the case that property is not actually “a thing”. It is instead a “right or a bundle of rights that are socially granted.” The right that most seems to define private property, is the right to exclude. But, if rights are socially granted then, as the Canadian political scientist C.B. Macpherson suggested, shouldn’t the right to not be excluded hold equal sway? Capitalism has so successfully naturalized the concept of private property that even asking these sorts of questions is seen as an aberration. Our willingness to accept and abide by this one way of looking at things excludes us from acknowledging that others are possible.

Hern explores a wide range of theories and policy ideas that could potentially remedy expanding inequalities between those who profit from private property ownership and those who suffer under it. One idea raised is that of a land value tax, most closely associated with Henry George’s 1879 book Progress and Property. In it, George argued that the state was wrong in taxing labour excessively while “allowing people to accrue unearned rewards via property appreciation and speculation,” as Hern puts it. George advocated instead for landowners to pay a tax based on the assessed value of their land.

Hern also makes the case for community land trusts, whereby a parcel of land is collectively purchased by a community organization, and dwellings on the land can then be bought separately and for considerably less cost than when they are bundled with the land they sit on. Resale caps or covenants are built into agreements to ensure long-term affordability and to eliminate flipping.

For Hern, there is no silver bullet solution. These are just two options that could help transform our relationship with land from one that benefits those who can afford to own it, to one that benefits everyone.

There is no technical barrier to implementing these types of solutions. The real barrier is political will. People have to demand solutions—like community land trusts and tax reforms, as well as co-op housing and all the various forms of non-market housing—and vote for politicians who will implement them. With more people in cities across North America facing barriers to housing than ever before, surely now is the time to do so.

The increasing concentration of wealth and power can make us feel naive, foolish even, for daring to imagine a different future is possible. But as Hern identifies, with “time, patience and incremental unwinding”, of course, it is possible. What it requires from the start is a collective will to reject the idea of property ownership as the solution to the problems this very idea has created.

***

For more information on What a City is For: Remaking the Politics of Displacement, visit the MIT Press website.

**

William Dunn and Claire Adams live in Vancouver, BC.