The City of Vancouver’s Broadway Plan has been released for public comment and is full of dramatic proposals. Profusely illustrated, over 100 pages long, the plan gives citizens a lot to chew on during this busy season. So here is a guide to what the plan contains and five key questions it leaves unanswered.

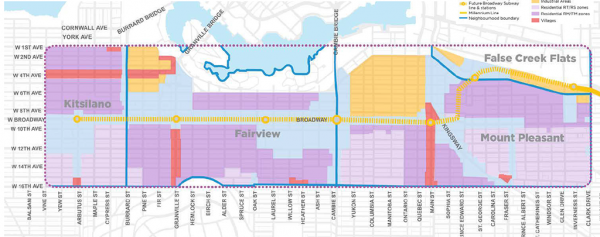

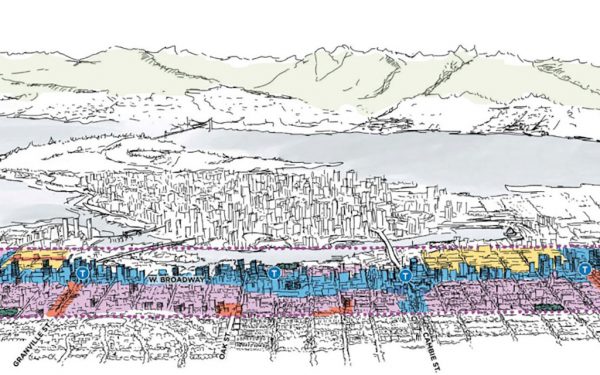

The plan anticipates adding 50,000 residents housed in 25,000 new units, all built within a ten minute walk of the new Broadway subway line. A rough balance between residents and jobs is anticipated with up to 42,000 new job sites projected.

The area covered by the plan covers about seven per cent of the city land area, and if population trends play out over the next 30-year build-out phase, this area will absorb about 44 per cent of all the city’s population growth over that period.

The plan organizes the subject neighbourhoods within its boundaries into four schemes: “centres, villages, residential areas and employment areas.” These areas roughly map over what is there now. The full length of Broadway along with some of the adjoining blocks are termed “centres.” Areas currently zoned industrial are “employment areas.” Neighbourhood shopping streets such as South Granville, Main Street and Fourth Avenue are “villages.” Everything falling outside these zones is deemed “residential.”

The plan is heavy on urban design details, with appealing illustrations that do not always successfully obscure the heights of new towers. The plan also includes a list of ambitious goals. These include new civic infrastructure, ecological performance and affordable housing — for which no specific targets or examples are provided. This absence suggests a set of questions that council will need to grapple with prior to the planned spring tabling of the plan for approval.

1. Will this housing be affordable to city wage earners?

No specific targets for affordable housing are provided except in the case of existing apartment buildings slated for demolition. In such cases residents are assured that there will be one-to-one replacement of their rental unit provided at current rents (the city of Burnaby already does this).

Otherwise readers are left to guess how many units will be affordable. And if current history is a guide, there will be proportionately few.

The word “affordable” occurs 85 times in the text, but without any numeric or proportional targets provided. Also, the word “affordable” is often conflated with largely unaffordable housing types. The plan speaks, for example of “buildings that deliver affordable housing (e.g. secured rental housing, below-market rental housing or social housing).” Why conflate secured market rental with other more legitimately affordable housing types? New rental units built recently in the city are only affordable to the top 10 per cent of city wage earners.

On the plus side the plan signals that new market projects will be subject to the city’s new development cost expectation tax designed to tamp down land speculation along the corridor, and that these taxes will fund some affordable housing. But here again, the plan does not yet specify what percentage of these funds might be directly applied to solve the affordability crisis. At the currently set level of $340 per square foot, this tax on up to 25,000 housing units could produce over $8 billion. Even if only half the new units were thus taxed it would amount to $4 billion, enough to cover the construction costs for 8,000 units of affordable housing.

Council should be given an accurate accounting of these resources and how they might be deployed. In that discussion this DCE speculation tax might be revisited and raised. The $340 figure was set in 2019 to quell land price speculation along the corridor. Since that time speculation along the corridor has raged ahead unabated, suggesting that the DCE is, if anything, too low for its intended purpose. It should be adjusted to achieve its intended purpose and provide a larger fund to ensure that at least 50 per cent of new units are truly affordable.

2. What are the jobs we expect along this corridor and will those wages match the price of housing?

The plan does not address what seems a key question. What will the new jobs be and will those wage earners be able to afford the rents or mortgages charged for this new housing? We know that larger numbers of Amazon and Microsoft employees are set to arrive in Vancouver. But the salaries for Canadian workers in those corporations are less than what their American equivalents are paid. And certainly tech workers will need food services, health care, tax filers, retail services, teachers, taxi drivers and all the other service workers that keep a city running. Projections of average wages and appropriate market prices for new housing and wages needed to sustain these units would not be hard to compute at this stage and should be part of any major plan such as this one.

3. Will our new zoning authority be used for public benefit?

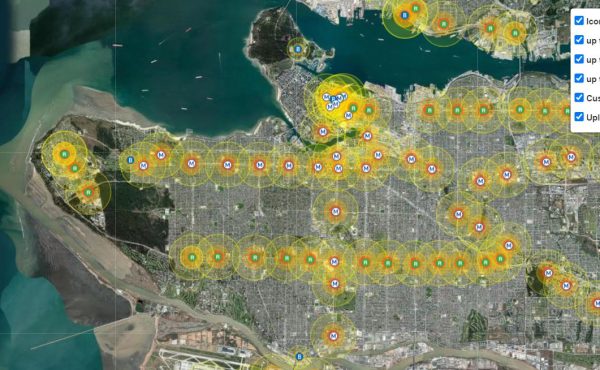

B.C. municipalities now have the power to zone by tenure. This means that the city, in the context of “upzoning” these eight square kilometres for far more density, will have a one-time-only chance to designate a certain percentage of these newly zoned lands for rental-only and/or co-op-only housing.

Such a move would also be a means of controlling land price inflation — the root and branch of our affordability problem. When land is zoned for developments that fetch the highest price — and in Vancouver that means high-density strata units — it zooms upwards in value. Land speculators use their information networks to see this coming and bid up the price of such land sometimes even before the zoning happens, much less before a development is slated.

An effective way to combat this ever-higher spiral in land costs is to bar certain lands from such uses, or tax such uses so heavily that other kinds of developments on the land make more sense financially. The result in either case: less land price inflation and therefore lower unit costs.

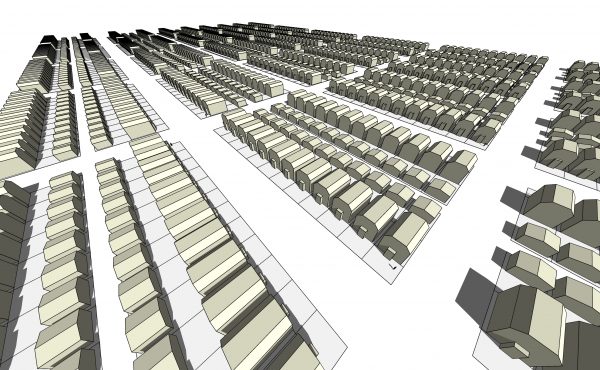

4. Must every new building require a large parcel ‘assembly’?

Here is another question related to how serious the city is about keeping land inflation in check. We have all seen the signs around town on arterial facing lots shouting “for sale, land assembly.” Such assemblies have in many cases led to fantastic increases in parcel prices as owners understand the leverage they hold over the fate of the big project by selling or not.

Land assembly projects tend to involve prototypical new buildings that require one-third block, half block, or full block assemblies (of typical 33 foot parcels). Perhaps it is now time to ask whether it would be better to seek lower densities in order to make such dramatic assembly no longer required. If we are looking for densities below 35 dwelling units per acre these can be had with minimal or no lot assembly, eliminating the land price inflation that lot assembly triggers.

A good example of this form is on the corner of Vine Street and 10th Avenue. It delivers over six times the density of a standard detached building on a standard Vancouver lot. But building it did not require lot assembly. The result is more than adequate for the population increase in the designated “residential areas” of the Broadway Plan.

5. What about civic space?

The plan provides zero indication of where new civic spaces (parks, schools, playgrounds, community centres, daycares, libraries, etc.) might be located. This is a big departure from previous and successful Vancouver planning efforts. In both the Yaletown and Olympic Village planning processes, for example, these elements were among the first things factored into initial planning drawings. Now we have a planning effort that anticipates multiple times more new residents than Olympic Village, yet ignores the very features that made Vancouver’s higher density areas famously livable. Council deserves better than this before being forced to vote on such an incomplete plan.

***

This piece was originally published in The Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC Urban Design program.

One comment

great questions! affordability is a joke in this city! land assembly needs a good think through before it envelopes the rest of the city(and rest of the lower mainland)