: : : : : : : Lest we think that these are bad times for pedestrians, it’s worth taking a look back through Toronto’s history to the days well before the automobile became the walker’s scourge. In fact, a quick glance at dangers and annoyances past confirms that the walker’s lot is not a happy one. Take bears, for instance. Bay Street was originally called Bear Street, after the bear someone once chased all the way down the street to Lake Ontario. Bears were a common sight in old York of the early 19th century. In 1809, Lieutenant Fawcett of the 100th Regiment encountered a large bear on Yonge Street — he cut its head open with a sword. Street brawls were another occasional danger. A King Street skirmish, between Samuel Jarvis (who also headed the mob that trashed William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing press) and John Ridout, led to a fatal duel in 1828. Speaking of duels, the Attorney-General was killed in Toronto’s first duel in 1800, and the website for Jarvis Collegiate (a wonderful source of historical tales) explains, “Although duelling was in its last days as a socially acceptable practice, there still remained some of the old attitudes which tolerated it. The laws called it murder, but many people still believed that, so long as the duel was fair, no one should be punished for it.” The Rebellion of 1837 is inseparably tied with Mackenzie and his men’s march down Yonge Street from Montgomery’s Tavern (just north of present-day Eglinton). Near what is now Yonge and Dundas, the rebels met a militia force, fired once, and then fled back north. The next day militia troops marched to Montgomery’s, where a dozen rebels were killed in clashes. Pickpockets and uncouth fellow-walkers are two hazards that author Susanna Moodie describes (on a trip to Toronto’s Provincial Agricultural Fair): “...the human bipeds, who pushed and elbowed from side to side anything that obstructed their path.” And then there is the mud. In its early days, Toronto north of Queen and Yonge was pure forest and north of Grosvenor (the street 2 blocks north of College and Yonge) was filled with subterranean springs and quick-sands. Pathmasters kept roads in order and householders had to do work duty on the roads. The waterfront used to teem with wild ducks and muskrats, and you could stroll along the shore and shoot at ducks flying up from the water, if that was your cup of tea. Being a new and seemingly wild country, building roads was a priority. Unfortunately, Toronto’s status as a place founded for trade and based on trade meant that roads were for industry and transportation of goods; the pleasures of ambling on foot were only ever an afterthought in city planning for roads, though in those early days King Street was a lively shopping district. Despite the obstacles, pedestrians made sure their footsteps were heard. Jesse Ketchum, who came to York from Buffalo in the early 1800s, was among the first to introduce sidewalks to the city, in the 1830s. Author and historian John Ross Robertson writes, “the streets were in a deplorable condition at certain seasons of the year on account of the mud; Yonge Street was particularly bad, and it was with the greatest difficulty that loads could be drawn along it. The sidewalks which Mr. Ketchum laid out were of tan bark, clean and dry.” Despite this initiative, the lack of sidewalks was a cause of poor school attendance until the 1890s. From Toronto’s earliest days, walking was a crucial means of transportation. For those without wagons or carts, it was the only one. And even if you could afford a team of horses, much of the time, you walked. In the 19th century Bathurst Street north of Queen was a semi-private path called Crookshank’s Lane, and north of Bloor it was just a muddy trail. E.C. Kyte, a Toronto historian, describing dances held in the ballroom of the Red Lion at Bloor and Yonge, notes that “although it was then a long and muddy way from town, the entertainments given there were always well attended. People walked in those days.” |

|

. For a few summers in the 1970s, Yonge Street was turned into a huge pedestrian mall. This image was captured in 1973. |

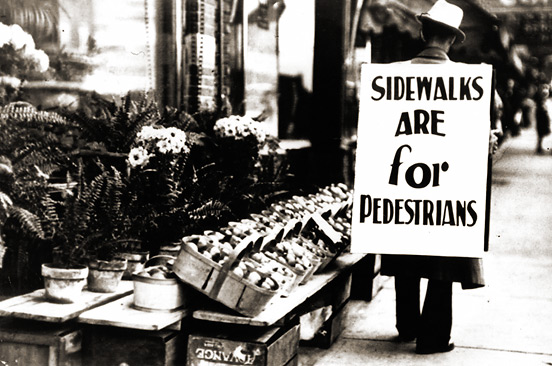

For the most part, Toronto follows a rigid grid-pattern of streets neatly laid out from the edge of Lake Ontario, in the interest of establishing property divisions for the ownership of lots. With a pronounced lack of hills that give cities like Montreal, Paris and London interesting viewpoints and winding lanes, Toronto is not an obviously interesting place for flâneurs. But then, Toronto’s charms have never been obvious. The current pedestrian life of the Annex, for example, owes much to real estate developer Simeon Janes, who laid out most of the area in the final decade of the 19th century, and who hated driveways. In his street plans he relegated stables, tradespeople and garbage collection to back laneways — although largely hidden now, you can still walk through these laneways which create a quieter, secret network for walking. In the 1830s, council began working towards gas street lighting, allowing pedestrian life to begin flourishing at night, and in 1841 the city contracted for the first gas street lamps. According to the Pedestrian Planning Network, Toronto’s first pedestrian killed by a motor vehicle was Hannah Heron, who had both her legs run over by a streetcar on September 2, 1892. The 61-year-old woman was visiting her aunt and was about to catch a trolley home on the Church Street line. Streetcars had been introduced to Toronto only three weeks earlier, and many city folk were unfamiliar with the capabilities of the modern trolley. The two motormen operating the trolley were as unfamiliar with transit cars as Ms. Heron — the driver had one day’s experience, while the other had not yet passed an examination for competency. But the police found the victim and drivers at equal fault. As we get to the 1930s, the car becomes the obvious principal problem for walkers. But beyond traffic laws and budget allocations that prop up the inefficient car at the expense of pedestrians, the laws that affect street life and foot travel are numerous and unexpected. They touch on sex, poverty and wealth, and often race as well. On occasion foot travel is welcomed as a money-making prospect. For example, in the early 1970s, local businesses strongly supported the Yonge Street Mall, which stretched from King north to College. In 1857, a year of severe economic depression throughout Ontario, the streets of Canadian cities swarmed with beggars and vagrants. Alexander Manning was re-elected as mayor of Toronto in 1879 on a platform which included cleaning up dirty streets. William Holmes Howard, elected in 1886, likewise targeted the problems of “drunkenness, slum conditions, filthy streets, and foul water supply.” Today we see the same mentality in the selective application of the Safe Streets Act to target the poor and down-at-the-heels. As with vagrancy laws a century before, it really depends on who is doing the walking. Despite the lack of support for pedestrians, despite the legislation that stalks our footsteps, despite the cars that rule almost all of our sreets, there is hope. Not, as we might wish, for a city where pedestrians benevolently rule, but perhaps at least for small steps towards co-existence. In 1997, Toronto finally created a resident committee dedicated to pedestrian issues. The Toronto Pedestrian Committee advises staff on pedestrian issues, provides for public consultation on these issues, and promotes the idea of walking as a way to get around. On May 21st, 2002, Toronto City Council adopted the Pedestrian Charter, a commitment to a pedestrian friendly city that is at least symbolically important. The Charter is meant to “promote awareness of the personal, social, and environmental benefits of walking as a safe, healthy, accessible, and sociable mode of transportation, especially for short trips; articulate a vision of the physical, social, economic, legal, and psychological framework required in order to encourage more people to walk, and to walk further; and raise awareness of the need to acknowledge the walking component of public transit trips as an integral part of the city’s transportation system.” “Pedestrian offences,” as the police like to call them, made news this spring, when Toronto’s finest launched a March-break program called Operation Ped Safe to save us from untimely squashing. Since they are trying to save us from ourselves, we dearly hope the police will stand at corners and ticket drivers who endanger pedestrians for more than just two weeks a year. Maybe then walkers will finally feel like they are taken seriously in this city. |

|

spacing.ca || contact || subscribe || in this issue || stores (c) 2005 Spacing Publishing |