In an era pre-occupied by “starchitecture” and the dominance of global cities, New Yorker architecture critic Paul Goldberger makes a persuasive case for the importance of workaday structures and the limitations of urban planning.

“I don’t buy the notion that you can draw a clear line between great architecture and ordinary buildings,” he said Friday during the Canadian Urban Institute’s Designing Cities symposium. “Each structure has something to say about the culture that built it.”

Goldberger has just released a new book entitled, “Why Architecture Matters” (Yale), in which he sets out to mine the meaning of Winston Churchill’s famous aphorism, “We shape our buildings and thereafter they shape us.” Architecture, observed the Roman builder and engineer Vitruvius, encompasses “commodity, firmness and delight,” and Goldberger, a Pulitzer Prize winner, cites this enduring definition to point out the paradox at the core of the most visible of all art forms. A building has to be “both useful and the opposite of useful,” he says. “It makes sense to think of architecture as both great masterpieces and daily experiences… Sometimes, it is the average [building] that tell us the most.”

The current recession, he said during an interview with me on Friday (the full conversation will be available on Spacing Radio on the December 7th episode), has dampened demand for good design. “In the very short term, we’re going to struggle to have architecture at all.”

Looking beyond the recovery, however, Goldberger feels the next wave of architecture will focus on the need for highly flexible design that recognizes the changing nature of family life. He also predicts that sustainable design “will become so taken for granted that we’ll stop talking about it.”

Goldberger further argues that bold experiments such as New York’s High Line, Broadway’s new “piazza” and the West Toronto RailPath mark a distinct trend in the way cities are thinking about the purpose of open space. “We’ve viewed public space as being about stasis — it’s where you sit and don’t move.”

With cities lacking both money and space to create new Central Parks, they are looking instead to linear parks as a means of re-claiming waterfronts or aging infrastructure. “Cities are about movement and circulation as much as anything else,” he observes. “We’re looking at places of movement as being public spaces.”

In New York, Toronto, and Ottawa, all these issues converge in brown-fields mega-projects — the Hudson and Atlantic Yards in New York, Lansdowne Live in Ottawa, or Toronto’s waterfront, the development of which is poised to get a big boost from the 2015 Pan Am Games.

Goldberger has written extensively about the problems facing the Atlantic Yards, a multi-billion-dollar mixed-use project focused on a new NBA stadium and destined for a 22-acre swath of Brooklyn’s waterfront. The project architect was Frank Gehry until this summer, when the developer, Bruce Ratner, fired him in favour of a less prominent commercial designer.

“These places present a real planning challenge,” he says. Such large swaths of urban land demand “some kind of large vision.” “Everything can’t be allowed just to happen.”

Goldberger points out that the re-development dynamic has almost reversed itself since Jane Jacobs fought Robert Moses’ expressway and housing schemes in Manhattan in the 1950s and 1960s. “If we leave our cities to grow naturally, they wouldn’t be places Jane Jacobs would have admired. We need to intervene.”

He warns, however, that there’s a risk of homogenization when vast sums of capital land with an “indifferent” thud in complex urban spaces, as is happening with the Atlantic Yards. “You can master plan,” Goldberger cautions, “but you need to allow incremental growth and planning guidelines that allow for variety.”

Still, the curious reality of our experience of built form is that even large and intrusive projects — he cites Stuyvesant Town in New York — will mellow with time. “Sometimes,” Goldberger muses, “the architecture doesn’t matter as much as we think it does.”

John Lorinc writes about urban issues for Spacing, The Walrus, and The Globe and Mail. He is also the author of the books Cities (Anansi Press), and The New City (Penguin Canada).

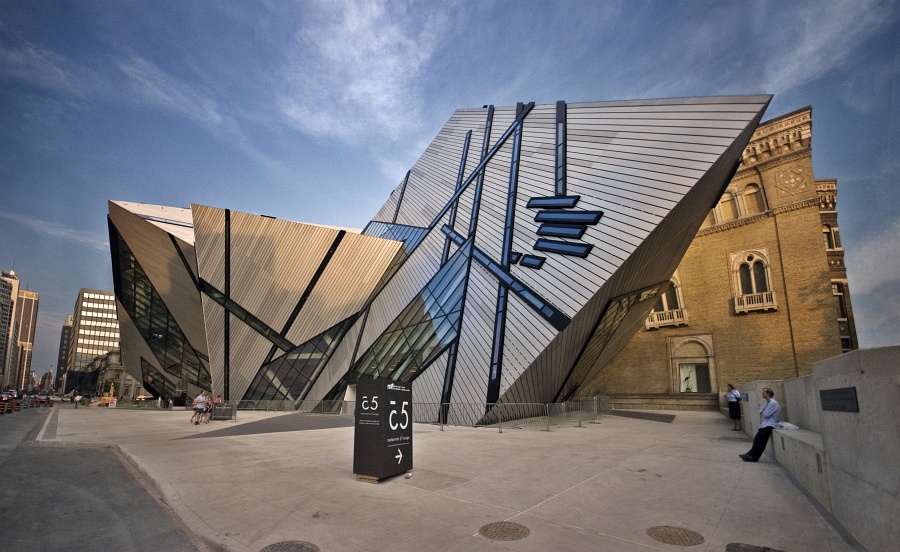

photo by Miles Storey

One comment

I hope HRM politicians take this message to heart when considering the Halifax Library project. All this talk about “landmark architecture” and “starchitects” generally just gives us totally unfunctional buildings and crappy public spaces.