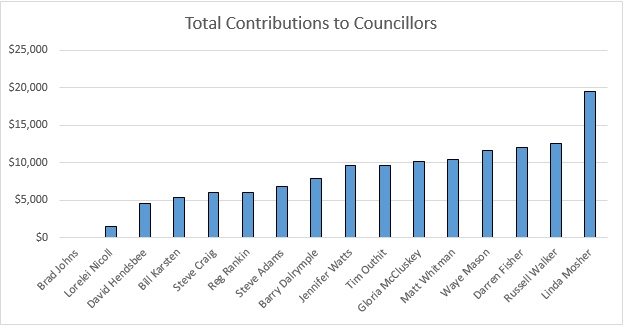

HALIFAX – Where did Halifax’s current 16 councillors get the cash for their 2012 campaigns? To find out for part two of Spacing Atlantic’s campaign finance series, I went through each councillor’s return. Adding up the contributions reveals that running for office in Halifax is expensive, with winning candidates collecting an average of $8,372 each in 2012. The $0 raised by Brad Johns and the $19,525 collected by Linda Mosher make up the extreme ends of the spectrum.

Where Did the Money Come From in 2012?

In municipal elections, there are two groups that are frequently cited as having both the motivation and resources to influence politicians and electoral outcomes through campaign contributions: unions and developers. For unions, the incentive to give political donations comes from the large number of mostly unionized employees that work for municipal governments while, for developers, it’s the municipal control of land-use planning. Both groups have an interest in municipal decisions. How do these two groups act in Halifax’s elections? Are unions and developers contributing large amounts of money?

An examination of the financial returns reveals that unions are not a significant factor in Halifax’s municipal elections. The successful candidates, now our councillors, raised over $130,000, but not a cent came from unions. Unions represented by the Halifax Dartmouth Labour Council did contribute to six unsuccessful candidates, but the total given ($5,325) was relatively insignificant. Unions are involved in municipal politics on an organizational and lobbying level, but they do not secure much influence through campaign contributions.

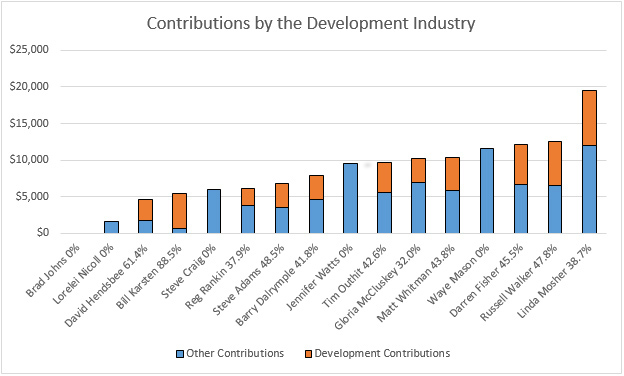

While unions aren’t a major source of funding, the story for businesses with an interest in land development including developers, construction companies and real estate firms (for convenience I will collectively refer to them as”developers”) is very different. Developers contributed a significant $47,467 in 2012, which was almost one third of all the cash given to councillors. In sheer dollar amounts, Linda Mosher received the most ($7,550), but because she raised so much money, developers actually made up a smaller percentage of her total funds (38.7%) than was the case for many of her colleagues. On a percentage basis, Bill Karsten collected the most with the $4,800 he received accounting for the vast majority (88.5%) of his funding. Five councillors, Johns, Nicoll, Craig, Watts and Mason, did not receive any money from developers, but for the other 11, developers provided, on average, 48% of their total funding.

The Most Generous Contributors

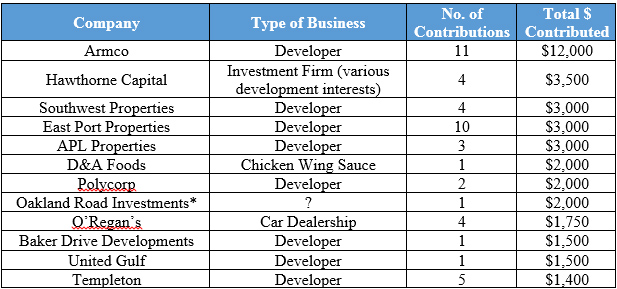

So who are the major corporate contributors? Only a few corporate donors gave more than $1,000 and, not surprisingly, almost all of them are connected to development.

The large corporate donors gave $36,650, which was 27.4% of the total $133,954 raised. Of the 13 large corporate donors, only O’Regan’s (car dealership) and D&A Foods (Dave’s Chicken Wing Sauce) didn’t have clear links to land development. D&A Foods only donated to one candidate, Gloria McCluskey, but on closer examination, the donation is more of a family contribution than a corporate one since the company is owned by one of McCluskey’s sons. I was unable to ascertain the business of Oakland Road Investments, which contributed $2,000, and as such, I have not classified them. All of the remaining nine large corporate donors had clear development interests.

Of the nine large corporate developers, Armco dwarfed all other contributors with a substantial $12,000 divvied up among 11 councillors. East Port Properties came close to matching Armco in breadth, providing funds to 10 councillors, but they didn’t give nearly as much money, just $3,000. Interestingly, another major contributor, Southwest Properties, has shown up in Spacing coverage of municipal elections before, as a large donor in St. John’s, Newfoundland. The nine large corporate contributors with development interests collectively gave $30,900, which accounted for 63.2% of the $47,467 donated by developers and 23.1% of all contributions. What all of this means is that developers, as a group, are not only the most generous contributors to successful candidates, but that just a few big companies are providing most of the development related money.

Hedging their Bets or Supporting Democracy?

A few unsuccessful candidates also received money from large corporate donors. The bulk of this money went to the five unsuccessful incumbents, but five challengers also received a handful of donations, setting them apart from the other 33 who didn’t. What’s interesting is that in a few races, Armco, East Port Properties, Hawthorne and O’Regans all made contributions to multiple candidates who were vying for the same seat. In District 12, Armco actually donated to three candidates: Mary Wile, Bruce Smith and Reg Rankin. The company read the political tea leaves in District 12 well, providing $1,000 to the victorious Rankin compared to just $250 each to Wile and Smith. There was also a lot of doubling up in District 1 where Armco, East Port and Hawthorne couldn’t decide between dueling incumbents Steve Stretch and Barry Dalrymple. Decisions on contributing for the big players are clearly more complicated than “which candidate do we prefer?”

Contributions from Individuals

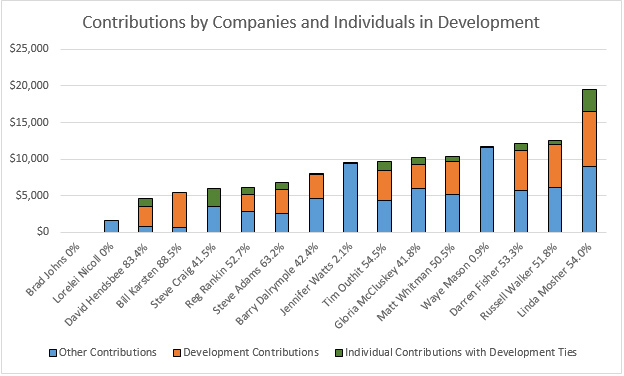

The overall picture that emerges is that the development industry is a major campaign contributor in Halifax’s municipal elections. CBC reached the same conclusion with an in-depth investigation back in April. I decided to take things one step further than CBC did. As well as identifying the companies involved, I went through each donation made by an individual and googled the contributor’s name to try and figure out who they were. It wasn’t possible to ID everyone, especially for common names such as Rob Smith, but I was able to make a reasonable identification for a large number of the individual contributors. Why did I put myself through the effort? To try and get at how much money also flows into municipal campaigns through personal donations from individuals with a financial interest in land development. These contributions are identified as personal, but from a practical point of view, it really doesn’t matter if the money is coming from a developer’s company or his own bank account, the potential influence on our political system is the same. This is especially true for personal donations from corporate CEOs or primary shareholders where separating the individual from the corporate interest is virtually impossible.

By looking at individual interests, I was able to identify an additional $13,050 in contributions from the development sector. Jim Spatz of Southwest Properties and the Fares family of WM Fares and King’s Wharf were particularly generous, making personal donations to several candidates totalling $3,600 and $2,300 respectively. Spatz’s contributions were on top of the $3,000 that his company also contributed. Once individual contributions are taken into account, the total raised by councillors from development interests increases significantly.

In the revised figures, Steve Craig’s results are particularly illustrative. All of Craig’s contributions came from individual citizens, but $2,500 (41.5% of his funds) came from six individuals with links to the development industry, which included the CEOs of Cresco, Southwest Properties and Scotia Materials. Craig didn’t break any rules and there is absolutely nothing to suggest that there was anything untoward intended (from observing him at council, I would be shocked if there was). There is a more general problem with Craig’s approach though: the potential influence of developer’s is hard to spot. A clearly identifiable donation from Cresco or Southwest Properties would, in many ways, be more transparent because the corporate name is more easily recognizable than the CEOs. Similar, but less dramatic increases in the percentage of contributions with links to development can be seen for councillors Hendsbee (+22.0%), Mosher (+15.3%), Rankin (+14.8%) and Adams (+14.7%).

The interaction between development money that flows to councillors directly from corporations and the money that arrives via personal donations from business leaders suggests that banning corporate donations, as has been done in many provinces and at the federal level, would be purely symbolic. Ban developers from making corporate contributions and the money will just get repackaged as a personal donation and the returns for the 11 councillors who accepted corporate contributions from developers will look like Councillor Craig’s. Like whack-a-mole, the money will just pop back up in a different form that’s not as easy to spot, creating the illusion of grassroots funded campaigns. If we want to actually change the makeup of contributors and dilute the potential influence of wealthy interests, a more comprehensive approach is required. More on regulatory options tomorrow in the conclusion to my three part series. Stay tuned.