The Nova Scotia government really, really wants to tear down one of Canada’s greatest, grandest 19th-century office buildings. And that’s about the only thing they can say for sure.

HALIFAX – The Dennis Building—once called the “finest office building in Eastern Canada—has survived 151 years and one near-fatal inferno. But it may not be able to survive the current provincial government, who insist that it now needs to be demolished and replaced with, well… they haven’t gotten to that yet.

All they know is, it’s got to go.

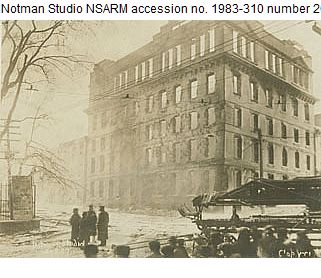

Built in 1863 as the headquarters for a dry-goods firm, the Dennis earned its name when William Dennis, then owner of the Halifax Herald, purchased it. We already almost lost it once, to a fire in 1912 that left nothing but a burned-out stone shell.

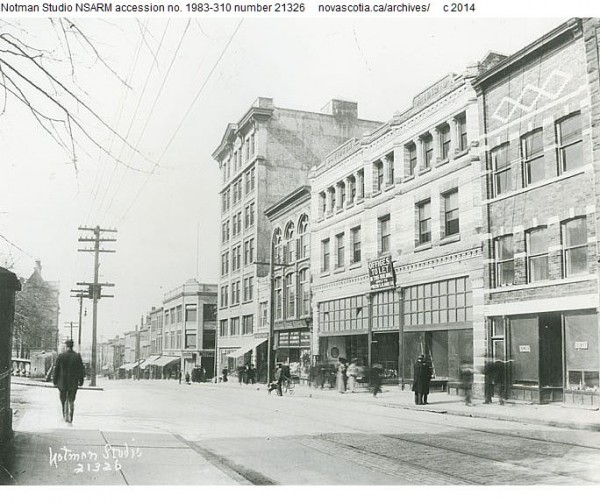

But rather than knock it down, architect George Henry Jost restored the ruined builiding and added three storeys to the top, leaving us with the imposing, resoundingly urban bearing of the Dennis Building today. It’s the earliest surviving example of a structure explicitly built to reflect the architectural classicism of the Province House area, forming the western flank of one of the most impressive collections of public buildings in Canada. And even as 20th century developments whittled away the neighbourhood’s once grand buildings (pictured below) for surface parking lots, the Dennis remained.

But, dismayingly, decades of disprepair and decay at the hands of successive governments culminated last May when, facing mould problems, employees were removed from the building. Today, Minister of Internal Services Labi Kousoulis says the building is “way far beyond repair” and must be demolished, reflecting the recommendation of a report prepared for the government by local firm Kassner Goodspeed Architects (which, notably, does not say demolition is necessary, but does recommend it).

This has all earned it a spot on Heritage Canada’s top ten list of endangered Canadian structures, who even sent a letter to the Premier.

It seems like nothing short of a massive public-opinion campaign will sway the province to restore the building.

So what comes next?

There’s a potential silving lining: Minister Kousoulis has repeatedly stated that the building’s original stone facade (its first four storeys, not including Jost’s 1912 addition) will be dismantled, catalogued, and stored. Most recently, he’s stated to the Chronicle-Herald that the province is looking to partner with a developer to redevelop both the Dennis lot and the currently vacant adjacent land. He said: “It is very key when you look at (the) town clock all the way to the waterfront. Our leaning is to incorporate the facade into the new building, but we’re not going to commit to that and paint ourselves into a corner.”

There’s a whole lot happening in that sentence, so let’s break it down:

1. “We’re not going to commit to that:” If the building is so historically important (which it is), and if it’s so architecturally significant locally and nationally (which it is), and if the only reason it’s being torn down is due to a state of extreme disrepair (which the government says is the case), why can’t the government make rebuilding the Dennis a condition of redeveloping the entire site? Minister Kousoulis says that the type of redevelopment proposed by a (so far hypothetical) partner will dictate what happens to the facade. Why the government itself can’t dictate terms in regard to their own property is unclear.

2. “Our leaning is to incorporate the facade:” Does this mean rebuilding the Dennis’ facade around a modern frame, essentially making it indistinguishable from the current incarnation, and then building brand-new structures on the adjacent lots? Or does it mean building a glass tower and awkwardly wrapping the Dennis’ old stone blocks around it, turning what was once a building into little more than three-dimensional wallpaper? Or does it mean even less—using a few stones and lintels here and there to pay the least possible homage to the past while claiming to be “re-using” the facade?

The Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia is adamantly against any of the above options, insisting the building must be maintained in-situ. They’ve even taken some tentative steps into the world of online activism with a website and Facebook group about the building.

But the idea of dismantling the building and then reconstructing the original facade around a modern frame may be a workable solution. As long as said reconstruction takes care to preserve the massing and profile of the existing building—as long as, from the street, it ends up looking as if it had never been taken down has been done before. Some of these examples can give us a sense of what a rebuilt Dennis might look like.

It’s been done in Edmonton, where the Alberta Hotel was demolished in 1984 to make way for a new office complex, but its facade was saved and stored.

Edmonton architect Eugene Dub oversaw a major rebuilding of the original facade over a new steel frame. The hotel bar was reconstructed with Victorian trimmings and decorative elements, and the rebuilt Alberta Hotel has since become a major landmark on Jasper Avenue, and headquarters for community radio station CKUA. If you didn’t know it was a recent construction, you’d assume it had been there for a hundred years.

It’s been done in Winnipeg, where a dilapidated commercial building in danger of collapse (and in far worse shape than the Dennis) was dismantled piece by piece and reconstructed around a brand-new parking facility.

This demolition—taking down a major historical building for a parking facility—was still controversial, but it proves that facades in dire shape can still be repurposed, and profitably. (This was a private-sector project.)

BEFORE:

AFTER:

And it was done in Toronto last year, when a building at the corner of Yonge and Adelaide was demolished to make way for a new development, but not before its facade was carefully dismantled and reconstructed around a new structure a block away, appearing indistinguishable from the original building.

It even happened right here in Halifax, where the west side of Granville Street was dismantled stone by stone, and rebuilt as the facade of the Delta Barrington.

So if it comes to it, dismantling and rebuilding may not be as outlandish as it sounds. But the government’s unwillingness to make anything but the vaguest commitments mean that there are countless caveats between now and then.

And countless questions: How will the building be disassembled to ensure the integrity of the facade? How will it be stored? When will we see a plan for the future of the site? Will the facade linger in storage for years, even as the site remains empty—another empty lot blighting downtown? When new construction does commence, will the Dennis in fact be reconstructed essentially as it was, restoring some of the area’s lost grandeur? And how long will the province allow downtown’s newest empty lot to persist?

While the minister has been adamant about the need to take the building down, there has been no further plan, no public consultation. So the unknowns are enormous, especially for a structure of such importance, on a major downtown site.

If the government truly feels taking the structure down and putting it back together again is the best option for the site, for the building, and for this city, that’s maybe feasible. But the building cannot simply come down without some plan for the future, some timeline to be acted upon, some promises to which the city and the public can hold the government accountable. The Dennis may not be lost for now, but it doesn’t have to be forever either.

Photos by Aaron Segaert, Nova Scotia Archives, Colliers, Heritage Winnipeg, and wfpquantum

3 comments

Good discussion of the history and architectural significance.

Dismantling and reconstructing is an expensive procedure. The structural engineer says the basic structure of the Dennis Building is sound, so the most cost-effective and responsible action is to repair the building and re-use it.

Isn’t it a lot more expensive to go with facadism, as opposed to restoration of the existing building? I have read that it could be between 50 to 30% more costly, depending on the ultimate use of the structure.

We’re losing the CBC building without a fight. We need to step up on this one. I wrote a letter to the minister a few months ago. Let’s keep up the pressure. It can be done!