When crossing this vast country, there is often the perception that the Canadian prairie landscape is rather homogenous and flat. Such gross generalizations of this region are quite unfair, as unfair as it would be for someone to make sweeping assumptions about Europe or Africa. To quote local playwright Kenneth Brown’s keynote speech at the 2013 Edmonton Heritage Symposium: “the devil is not in the details, but in the generalities.”

The prairie landscape that stretches from Edmonton to Winnipeg is known to ecologists as the aspen parkland biome – a transitional zone from prairie to boreal forest. In comparison to the semi-arid prairie surrounding Calgary, Regina and Saskatoon, aspen parkland features a wetter climate and a larger mosaic of wetlands/forests scattered throughout the grasslands. You can witness this with the decrease in tree stands as you drive along Highway 2 towards Calgary. Here, this subtle difference between the two prairie types has influenced local human history and culture, which in turn continues to shape the landscape around us.

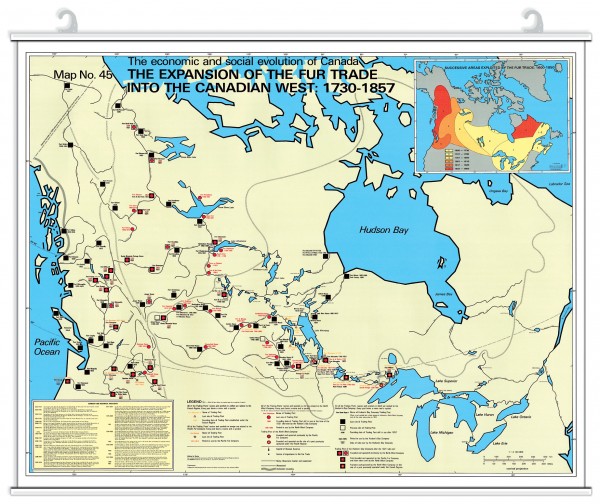

Because of the relative richness of wetlands and forests, First Nations living in aspen parkland did not solely rely on buffalo-hunting lifestyles, as did the tribes to the south. Unlike the semi-arid prairies, the environment offered more opportunities for fishing, trapping, deer/moose-hunting and foraging/production of many crops. This local knowledge proved instrumental during the fur trade and European colonialisation of the west during the 18th century, first by the French and then the English. It is no coincidence that all but one major fur-trading post was located outside the semi-arid prairie zone where valuable furs were not widely available. Fort Rouge (Winnipeg) and Fort Edmonton were established in 1738 and 1795 respectively – long before the numbered treaties, the construction of the national railways, and the establishment of Fort Calgary (1875), Regina (1882) and Saskatoon (1883).

The location of these fur-trading posts were influenced not only by the environment, but by human patterns as well. In the case of Edmonton, the North Saskatchewan River acted as a natural boundary for the Cree to the north and the Blackfoot to the south. During times of peace, various tribes would meet at the bend of the river (known as Pehonan or, more recently, Rossdale) as a gathering place for various activities, including trade. The Hudson’s Bay Company, wanting to expand and trade directly with the Blackfoot rather than indirectly through the Cree, set up the post where Edmonton is today.

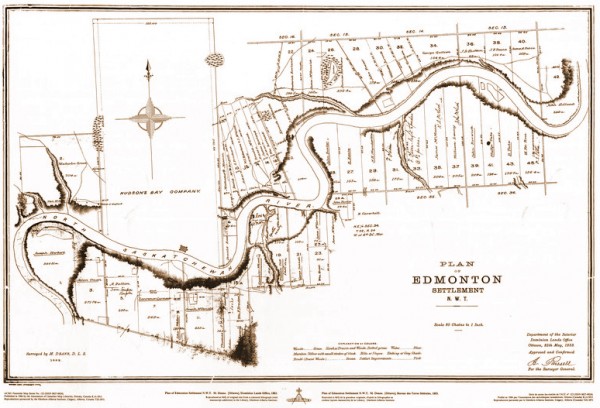

Despite being established by the English-speaking Hudson’s Bay Company, many of the trappers and people residing in Fort Edmonton were Cree, Métis, and Francophone – those who already had knowledge of the area. In fact, the fort was also called Fort-des-Prairies by francophones and Amiskwaskahegan (‘Beaver Hills House’) by the Cree. The legacy of these cultures can still be seen in Edmonton’s present cultural landscape, a history that distinguishes Edmonton from that of Southern Alberta: several existing/former Métis and francophone settlements have become part of the region’s fabric, including Edmonton’s French Quarter in present-day Bonnie Doon; community and street names such as Garneau, Satoo, Meyonohk, Grandin, Marie-Anne Gaboury, Lac Ste Anne, and Perron; an early street grid in Edmonton that aligns with the river-based seigneurial land distribution system; and perhaps many more.

The presence or absence of aspen parkland had an important influence on the prairie landscape and its people – something that Edmontonians should acknowledge as part of their collective memory and identity. The next time you look at the Alberta flag, take a closer look at the crest. Perhaps now you will recognize what sits between the foothills and the fields of wheat.