I had the honour of providing some opening comments at the Open Data Hack on Saturday, 24 May. If you were not there to catch the event, I am here to share my thoughts on open data and citizen engagement, something all Edmontonions should be interested in.

What is open data?

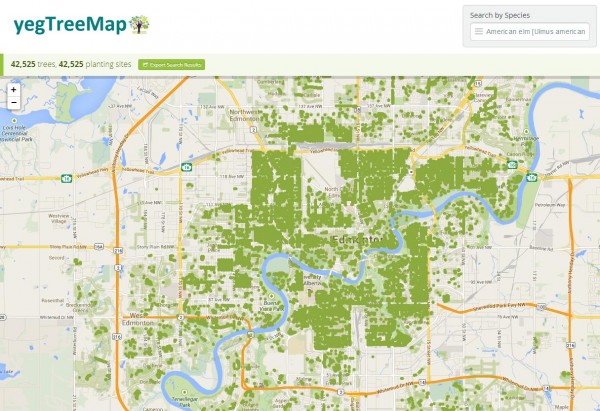

Open data occurs when a government shares the data it collects as part of its daily operations. This data can come directly from citizens (as in census data) or the data can be more administrative, such as garbage collection schedules and budgets. The data collected can have a spatial component, such as the roof line data set. Check out the City of Edmonton’s Open Data Portal to get a sense of the available data.

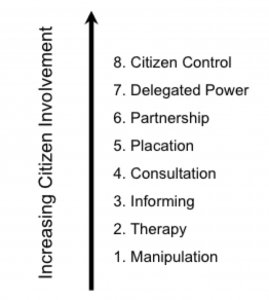

Within this context, open data is the corner stone of open government and transparency because it grants citizens access to one of the main tools of policy-makers. Although it is an outdated model, Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation is relevant as a point of illustration. It details the ‘rungs’ of citizen engagement that governments can engage in. They range, at the lowest rungs, from an Orwellian level of government manipulation of citizens, to the highest rungs where a partnership is forged between citizens and government so that the two are largely indistinguishable.

The goal with open data is to provide a level of engagement with citizens so that we can use the same tools and information as policy makers to confirm or challenge their conclusions. An engaged citizenry not only provides input into the problems of the day, but also may help define the issues, the range of possible solutions, and the implementation of those solutions.

There are three important components to open data: format, content, and community.

Format is important. Data shared through ‘closed’ formats, such as PDFs, cannot be easily imported into software that can analyze or visualize it. Given that the data is the starting point upon which good analysis is built, being able to manipulate the data is vital. Through analysis comes understanding and communication, and that requires some sort of interface, from something as simple as an article, to more complex such as an app.

When it comes to content, an open data portal is only as good as the data available. If only ‘soft’ data is released – data that does not contribute to a narrative or somehow empower citizens (i.e. does that data make those in government uncomfortable) then the most important data that citizens should see is being repressed.

For Edmonton this is important for two reasons. First, we have an engaged citizenry who are interested in a wide range of policies, from the downtown arena to bike lanes to budget allocations. Second, the City of Edmonton has been criticized for implementing inadequate public consultation plans. By posting, on-line and in an open format, the data that underlies any given policy the City is creating a more inclusive process. Normal citizens and experts alike can examine, comment on and criticize the rational for the policy of-the-day.

And this is where community comes into play.

This is a tall order, and currently unrealistic, to expect citizens to engage with data at the analysis and app development level. Enter the so-called hackers. Hackers provide an intermediate step between the data and citizens. They work to develop, either alone, or better yet with content experts such as researchers, planners, or even accountants, applications or evaluations of the data for citizens.

The end result can be wide ranging. For example, an app like Vancouver’s Recollect that reminds people when to put out the trash or the Guardian Newspaper reporting on British Government spending. Both the app and the reporting provide a service to citizens based on open data.

In addition to making iPad apps, the open data community should also act in the capacity of activists to lobby for more and better data, and to increase the ability of an average citizen to think critically about and work with data. After all it is inevitable that the data the City of Edmonton collects, stores and uses will become more important as a policy tool. As citizens, we should understand what is being used, and how.

2 comments

Very relevant. As I am interested in mapping, a friend of mine who is a GIS whiz and myself had the idea to plot the relationship of transit stops with a five minute walk radius to all property parcels. This is data that the city has, but currently charges for.

We are citizens doing (or would have done) it out of personal interest and for the greater interest of the city, for free. However, we could not find the data freely available or in formats that we could use.

I inquired with the city as to the use and price of the parcel data, and it would have cost me $20,000! Even without commercial use. It’s great that there is the initiative for this to change now in the City of Edmonton. That price came as a surprise to me as having moved from Vancouver where this data, and several other great datasets, are already freely available in their catalogue.

UBC’s School of Architecture and the planning school there use of these datasets in academic research projects, and in turn engage the public with a dialogue about design and planning.

Hi Jason,

Thanks for your comment and enthusiasm for open data. You make a good point in that there are many data sets that the City could release to the benefit of citizens. There are a couple of approaches that you could take if you are interested in pursuing the parcel, or other, data. 1. Create a user account on data.edmonton.ca and request data that you want. 2. Tweet @cityofedmonton a data request, you can also FaceBook the City of Edmonton a request. 3. Ask your councillor to open up the data.

In the mean time, check out the roof line data as it may be a reasonable substitute to the parcel data. I hope this helps.

Matt