Do skyscrapers ever grow tired

Of holding themselves up high?

Do they ever shiver on frosty nights

With their tops against the sky?Do they feel lonely sometimes,

Because they have grown so tall?

Do they ever wish they could lay right down

And never get up at all?– Rachel Field

It may be much ado about nothing, as it is unclear whether the proposal would be approved by City Council or actually get built, but this article in the Edmonton Journal last week about the possibility of a 71-storey tower, The Edmontonian, being constructed on the north edge of downtown definitely got a lot of attention, with 70,000 views in 24 hours.

Skyscrapers undoubtedly generate a lot of excitement. The name itself, a building that “scrapes the sky”, suggests a sense of awe. Particularly tall ones have the potential to inspire interurban competition. Indeed, The Edmontonian‘s architect was quoted in the article about the proposal saying: “Oh yeah, we wanted to beat Calgary” by making this tower taller than Calgary’s newest. But is western Canada’s tallest building, or for that matter the world’s tallest, really something to aspire to?

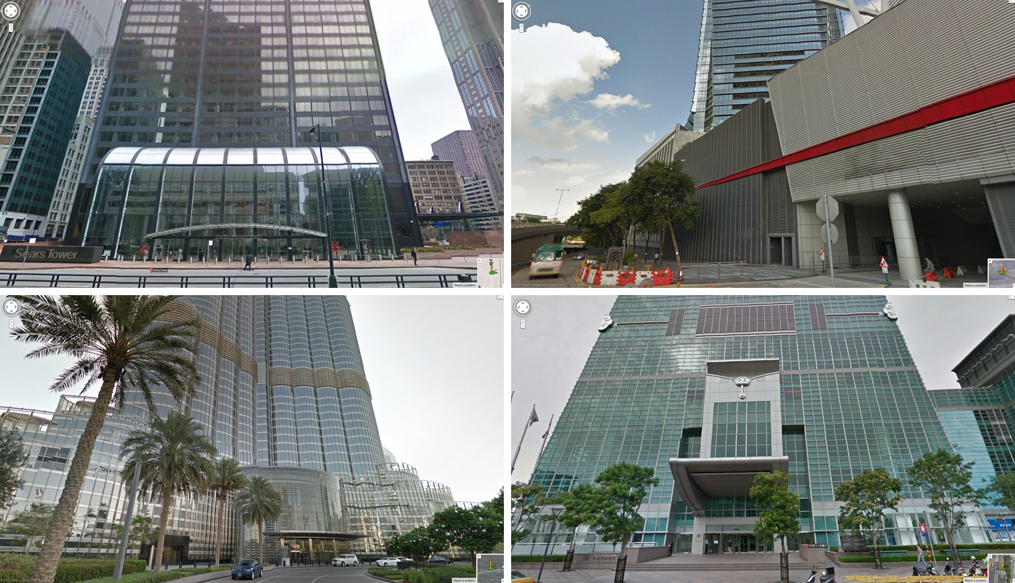

Although often lauded as high-octane shots-in-the-arm for urban vibrancy, ultra-tall towers do not guarantee it. A Google Streetview tour of some of the world’s tallest buildings reveals a surprising lack of street-level activity. In the four screenshots below, a grand total of 11 human beings can be seen. No really, they’re there if you squint.

If built, The Edmontonian would sit about a block north of Edmonton’s lonely northern downtown outlier, Epcor Tower. Like its world’s-tallest cousins, Epcor Tower has done little to spawn a renaissance in the surrounding area, despite being the daily workplace of well over 2,000 people a day. So what’s up? Why doesn’t height equal vibrancy?

In response to recent proposals to build more tall buildings in Paris, UNESCO’s Deputy-Director for Culture Francisco Bandarin stated:

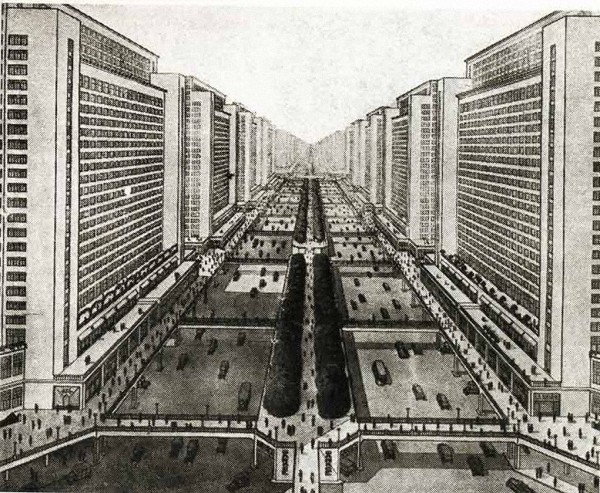

“The idea of densification with height, this is a misconception. A tower, because it needs a lot of services, it needs parking, does not help to make a denser, compact city. This is not a good model. This is not the future. Paris is a city that was developed in the nineteenth century as a city of just six floors, and this is what has given it its value. It is the most densely populated city: it is denser than New York thanks to its formula of just six floors.”

To this argument, I would add that extremely tall towers make it less likely that workers or residents will spend significant amounts of time at street level. Very tall buildings give over more of their ground floor to simple circulation, the funnelling of people and cars into and out of parkades and elevators, not lingering and interaction. But even if the design of the building at street level encourages people to interact, there is a question of ownership, of intimacy and belonging, that can exist in a building of 4 storeys, perhaps even 10 storeys, that seems to diminish as buildings reach closer to the clouds. At a certain scale, large buildings seem to lose their ability to support a sense of community, slipping back towards anonymity.

This is not to say that it is impossible that a tall building could be designed to support community, nor is it to say that every walk-up apartment building is a hive of neighbourliness. But I think there is definitely something to the potential of the mid-rise city to create activity at street level, open and accessible to all. London, Paris, Washington DC, some of the densest and most celebrated cities in the world, are primarily mid-rise cities. In the recent municipal election, the possible future of the City Centre Airport lands was likened to Brooklyn, New York’s bustling yet decidedly mid-rise borough. Our own Old Strathcona, late-night partiers aside, is an active and diverse urban neighbourhood of primarily 3- and 4-storey buildings.

So I say let Dubai, Shanghai and other international cities have their monster towers. We can even let Calgary have The Bow. Density is important to the urban vitality of a city, and Edmonton could benefit from more of it. But density doesn’t have to stretch all the way to the clouds.