Traffic circles are a distinctive part of Edmonton’s history. Common in Europe, circles were rare in North America, especially out west. Edmonton, however, was an exception and became the traffic circle capital of Canada after World War II.

In 1949, the City of Edmonton hired its first urban planner, Noel Dant. The city’s population was growing rapidly and car ownership rates were exploding after the discovery of oil. To address current and future traffic volumes, Dant imported the idea of traffic circles from his native Britain. In a 1954 summary of his work to date, he wrote that:

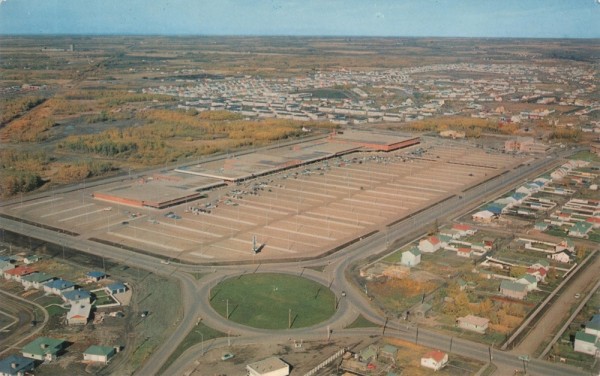

Intersections of important highways were in the first instance controlled by large-diameter traffic rotaries at grade; but in designing these intersections, enough land was reserved at the sides to be used for grade separation when traffic volume builds up to a point which cannot be handled by a simple rotary.

Seven circles had been built at that point; five more would be constructed. Most of Edmonton’s dozen eggs were placed in a ring about 3 km from the downtown core and close to the municipal boundaries of the time. Most were standard circles connecting four roadways but the Bonnie Doon circle had five legs. Another one at the northern end of Princess Elizabeth Avenue was elliptical and complicated by two additional local roadways and an alley.

Traffic circles are special. They don’t have the 24/7 power draw of signalized intersections and aren’t affected by blackouts. Except where traffic is excessive, they can reduce overall driver delay: vehicles entering them often aren’t required to stop or only need to yield for a few seconds before proceeding. Circles also help disperse traffic rather than creating platoons of vehicles coming off a light. Some studies show that traffic circles have lower collision rates than signalized intersections. Although in Edmonton this hasn’t always been the case, perhaps due to the drivers’ lack of familiarity with them. When crashes occur, they tend to be less serious sideswipe collisions since circles effectively design away the possibility of head-on or t-bone collisions. Finally, anyone who has made multiple orbits around traffic circles – which my teenage friends called “pulling an Erphon” after the name of the person who introduced us to the idea – or had a picnic or built a snowman within their innocently illicit interior space can attest to their uncommon appeal.

But the unique features of traffic circles haven’t saved them. The interchanges that Noel Dant foresaw replaced two circles. Five others were replaced with signalized intersections (one of which, at St. Albert Trail / 118 Avenue, retains the form of a circle). The Valley LRT line will eliminate the Bonnie Doon circle. Two others are on routes that parallel future LRT lines and thus may need to be removed to facilitate traffic flow.

A few modern roundabouts, smaller and lower-volume descendants of the 1950s-era circles, have been built in the city since 2000. They are effective and more pedestrian / bicycle friendly than their predecessors – we could use more of them! – but they don’t represent a direct connection to the heritage of Edmonton’s post-war built environment. Before all the original circles are gone, the City of Edmonton should consider giving one historic designation.

4 comments

Interesting piece.

Erik. It passed my mind today that Calgary’s blue ring art could be an excellent addition to a centre of a traffic circle. If Calgary no longer wants it, we should take advantage of an opportunity… http://www.cbc.ca/m/touch/canada/calgary/story/1.1930104

Great article Erik. Like the idea of the inside being this ‘semi-illicit’ public space.

After writing the article I was informed about the UK Roundabout Appreciation Society. Any traffic circle fans out there can check out the group at Roundaboutsofbritain.com.