Part 2 in our history of corruption in Montreal. Check Spacing Montreal each day this week for the latest “episode” in this century-long soap opera.

On April 1st 1924, a bank’s armoured vehicle came under attack in the tunnel on Ontario street, and the criminals escaped with $142,000. It was the biggest heist known in America at the time and, it turned out, it had been masterminded by an ex- Montreal police officer and an ex-detective. $13,000 would find its way into police pockets, in exchange for protecting the criminals. The public cried for an inquiry into Montreal’s police force.

Judge Coderre (who, incidentally, was one of the candidates defeated by the Citizens’ Committee in 1910) concluded that the police were undisciplined and lacked authority. For example, they regularly sold stolen goods back to the victims of crime. Perhaps that should have come as no surprise given that the police chief frequently abused his power to appoint officers, even hiring ex-convicts into the force. Following Cannon’s 1909 recommendations, the chief of police was directly under the control of the executive committee. During elections, police kept busy locking up opposition candidates, falsifying ballots, and otherwise preventing citizens from reaching voting stations.

Coderre’s report, marked by a conservative, Christian view of the law, focused on police’s failure to uphold “public morality”. The judge described the stubborn persistence of prostitution as a threat to the French Canadian population, on one hand a moral degradation of women, on the other a “race towards suicide” via STIs.

In an interesting twist, Recorder Geoffrion, the judge who regularly saw those arrested in brothels and gambling dens in his court, testified that he was personally responsible for the persistence of Montreal’s red light district. He told the commission that he could shut down the red-light district within a month, but instead he chose to hand out light fines whenever women were brought before the court on prostitution charges. The recorder felt that prostitution was inevitable and proposed regulation (in order to control venereal disease), rather than categorically outlawing prostitution.

In response, Coderre called in four religious experts of different Christian denominations to consider regulating prostitution. Unsurprisingly, they unanimously declared that all forms of Christianity condemned prostitution. Strangely, Coderre completely ignored Geoffrion’s admission of guilt in his report. Perhaps the judge did not wish to place scrutiny on the discretionary application of the law that was common in the city’s courtrooms.

Instead, Coderre recommended an independent police chief, more officers, and better supervision within the force. He also advocated keeping files on all immigrants – especially Italians and Jews – who he perceived as a hotbed of criminal activity. While several police personnel were convicted, Coderre placed the blame for the corrupt system on the city’s powerful executive committee – the group that Cannon had established to curtail favoritism among the aldermen.

The report was handed to City council, who turned it over to the executive committee. Needless to say, the committee did not sentence their own members: Coderre’s recommendations were squarely ignored.

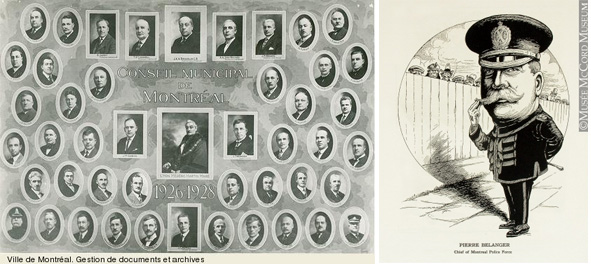

The following year, every single executive committee member was re-elected. Police may have lent considerable “support” to the incumbent counselors, given that many of their own would have been reprimanded if Coderre’s rulings were seen through. Médéric Martin, who had been among those convicted in the 1909 inquiry, was elected mayor.

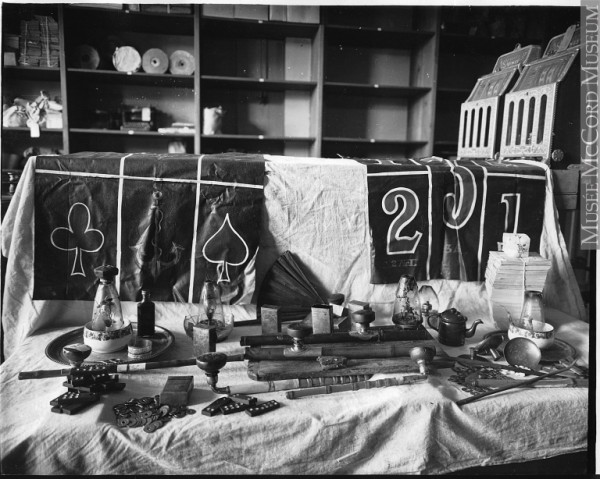

Top image: Drug and gambling paraphenalia, 1924 (?) from McCord Museum archives. Left: In 1926, the entire Montreal executive committee, who bore the blame for pervasive corruption in city hall, as well as mayor Médéric Martin, who was among those convicted in 1909, were re-elected. Source: Ville de Montréal archives. Right: Police chief Pierre Bélanger also kept his position Source: McCord Museum M20111.65.

Much of the information summarized in this post originates from: La délinquence de l’ordre by Jean-Paul Brodeur.