Part 3 in our history of corruption in Montreal. Check Spacing Montreal each day this week for the latest “episode” in this century-long soap opera.

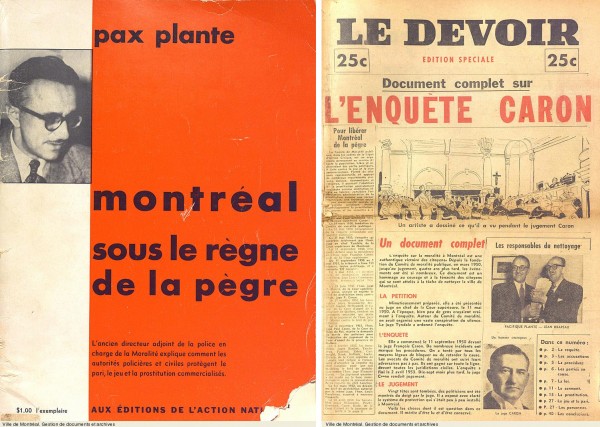

Between 1949 and 1950, Le Devoir ran 61 articles all written by Pacifique Plante, under the headline Montréal sous le règne de la pègre. During the 1940s, Plante had been chief of the police “morality squad” and successfully shut down brothels, bookies, lotteries, after-hours watering holes – even church bingo sessions. He’d had ambitions head the police force, before his rival, Chief Langlois landed him with a reprimand and eventually dismissed him from the force. Plante’s descriptions of Montreal’s underbelly in Le Devoir were rich with scandalous, yet titillating details, gleaned during his years as a lawyer in the recorder’s court, and then with the police morality squad.

Incensed by this relentless media blitz, citizens formed a Public Morality Committee to demand an inquiry. Plante became chief prosecutor, despite the fact that several accusations within the police force had actually happened under his own watch. His assistant prosecutor was Jean Drapeau, a lawyer who had previously run in two provincial and two federal elections without success (even losing to Communist candidate Fred Rose in 1943).

Judge Caron took on the impractical task of laying blame upon individual police officers and executive committee members for the general atmosphere of tolerance towards organized crime that had permeated the city for decades. 15,000 allegations were brought before court and in the end two dozen police were found guilty of infractions such as falsely reporting that they had padlocked a brothel door.

It took Caron 17 months to produce his report. The same day as it was released, Drapeau announced his candidacy for mayor of Montreal, and was elected soon thereafter. Plante also won his dream job: he was appointed police chief. The Caron inquiry may as well have been a $500,000 publicity campaign by two politically ambitious men.

Drapeau continued his morality campaign during the three decades that he remained mayor, going as far as clearing Mount Royal’s undergrowth to prevent couples (particularly gay lovers) from taking a romp in the bushes. He might have been more effective at eradicating illegal gambling: he introduced Canada’s first governmental lottery, originally called the “voluntary tax,” and opened the city’s first casino.

Much of the information summarized in this post originates from: La délinquence de l’ordre by Jean-Paul Brodeur. Images from Montreal City Archives: Montréal sous la règne de la pègre.