Montreal Corruption Retrospectives are all the rage these days, and for the spring 2013 edition of Spacing Magazine, which was released last Saturday, I put together a feature piece on corruption inquiries through the ages. Check Spacing Montreal each day this week for the latest “episode” in this century-long soap opera.

“Il semble que le déroulement d’une enquête soit un processus cyclique où l’on passe du scandale à l’indifférence.”

“It seems that inquiry proceedings are a cyclical process in which we pass from scandal to indifference” writes Jean-Paul Brodeur in his book La délinquence de l’ordre, published in 1984 (which was the source of much of the info here).

The “Royal Commission” of 1909 may have been the first to invoke the monarchy, but it was not the first probe into corruption in Montreal, nor even the first of the century. Inquiries in 1864, 1877, 1894, 1902 and 1905 had been attempted, ignored, abandoned, aborted, and hushed up, respectively. So it is little surprise that by 1909 citizens were clamouring for a general and complete scrutiny of all seven departments of city hall (police, fire, roads, hygiene and statistics, finances, water, and lighting).

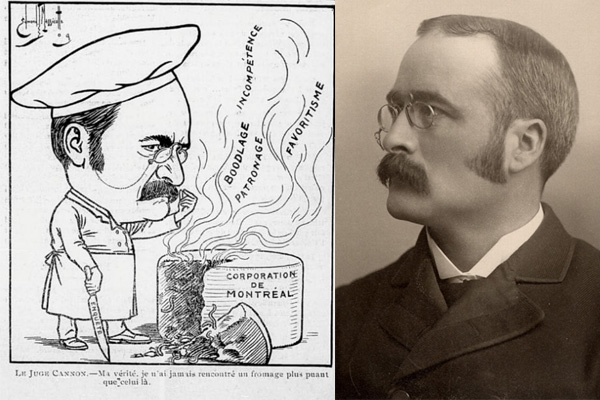

Judge Lawrence Cannon, who headed the inquiry, concluded that city hall was “saturated with corruption,” with no less than 25% of the city’s revenues making their way into the pockets of elected aldermen’s friends and family.

For instance construction contracts were sub-divided to bypass calls for tender, then handed over to firms in the aldermen’s inner circles. Furthermore, dozens of liquor-license infractions had been ignored when business owners contributed to election coffers, and a position in the police, detective or fire department could be negotiated for about $25.

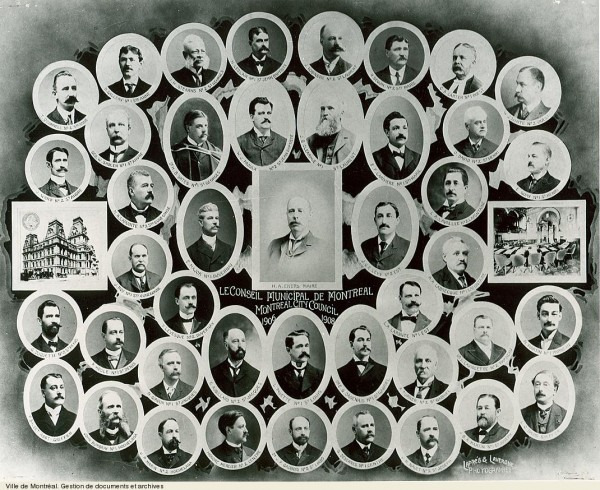

Cannon’s scathing report, which convicted 23 of the city’s 40 aldermen, was published in La Presse shortly before the 1910 municipal election. Anticipating the political consequences of his revelations, Cannon specified that the next elected city council would be responsible for implementing his recommendations.

Source: Ville de Montréal Documents et Archives VM6,S10,D015.22-5

The inquiry had far-reaching implications: the provincial government reduced the number of elected aldermen by half, a board of commissioners – which later became the executive committee – was created to oversee municipal services including the police force, and the police were endowed with a “morality squad.”

The citizens’ committee that had launched the inquiry ran their own candidates and won the 1910 election by a landslide. But with new faces in office, the inquiry was quickly forgotten: none of those convicted in the report faced civil or criminal prosecution.

—–

See the Judge Cannon’s report and recommendations on the City of Montreal website.

The caricature representing juge Lawrence John Cannon is from La Bombe, Sept 15 1909, and reproduced from Patrimoine, histoire et multimédias blog by Vicky Lapointe.