In these charter-charged times, it has often been pointed out that few things are less secular than a great big cross atop your parliament, or your city skyline. Many have also argued that these most blatant of government-supported religious symbols ought to be grandfathered into the landscape as heritage symbols.

But if certain crosses are to represent our heritage, perhaps it’s worth learning these particular cross’ stories. What history are we honouring if we preserve each cross’ place in the landscape? Scratch the surface and it seems that that cross-raising is always a little political, for better or for worse…

100,000 Children Help Raise a Cross on Mont-Royal

December 1642. The Ville-Marie fortress had been perched on the banks of the island for a mere 8 months, when the Saint-Lawrence river threatened to flood the foundling colony.

The colony’s 57 inhabitants looked to their leader, Sieur de Maisonneuve for salvation. Our city’s founding father entered into a desperate moment’s pact with the Virgin Mary: if the rising waters spared the fledgling colony, he promised to plant a cross on the top of the mountain. The flooding subsided, and De Maisonneuve upheld his side of the bargain: on January 6th 1643, the governor carried a wooden cross up the mountain side. To this day, a stained glass window in Notre-Dame Basilica commemorates his exploit (left).

Over the following decades, the wooden cross rotted away and was lost, but it is believed that the original votive cross was located near Sherbrooke and Côte-des-Neiges,

More than two centuries later, the the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste raised the notion of building a commemorative monument on the mountain top.

More than two centuries later, the the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste raised the notion of building a commemorative monument on the mountain top.

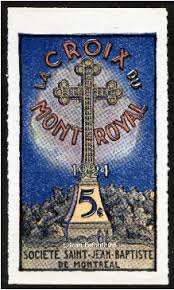

100,000 Catholic school children and 4,200 adult volunteers were recruited to help finance the project by selling 5-cent stamps. This young workforce was able to raise $10,000, but unfortunately that was not enough to complete the original design which included a concrete base and observation platforms in the cross’ arms. None-the-less, the 26-ton steel lattice cross was built by the Dominion Bridge company.

Imagine thousands of schoolchildren watching the cross they had invested in light up for the first time on Christmas Eve 1924. The monument could be seen in the night sky from 60km away.

In 2004, ownership of the Mount Royal cross was transferred to the City of Montreal. Beyond commemorating De Maisonneuve’s votive cross, the City’s heritage database points out that the monumental cross represented the French Canadian community’s hold on Mount Royal, whose slopes were traditionally a strong-hold of anglophone wealth.

“Traditionnellement perçue comme un repère de la suprématie économique anglophone, la montagne est investie par la communauté francophone en érigeant cette croix qui surplombe le flanc est de la montagne et qui domine le paysage montréalais.”

Our Dark Age Heritage: The Cross in the National Assembly

When Premier Maurice Duplessis hung a cross over the National Assembly in 1936, it’s clear that Duplessis’ intention was to revive the bond between church and state. It was the beginning of a 20-year period that has since become known as la Grande Noirceur.

Soon after the cross went up in parliament, Duplessis presented the Cardinal of Québec with a ring, the Cardinal replied: “Je reconnais dans cet anneau le symbole de l’union chez nous de l’autorité civile et de l’autorité religieuse.”

Duplessis won support throughout Quebec’s rural francophone régions by extolling the virtues of the church and the importance of protecting Quebec’s provincial autonomy. To do so, the premier fought against federal funding for universities, unemployment insurance, and health care, which were portrayed as communist threats, or as a take-over bid from the “centralizers” in Ottawa, and which undermined the authority of the church. At the time, the church depended on provincial funding to run schools, hospitals, and other social services.

But the true secret to his political success was the financial backing he received from the same anglophone and foreign businesses he railed against in his campaign speeches. They were happy to fund a campaign that ensured Quebec would retain the lowest wages in North America. Duplessis regularly used his provincial police to break up picket lines and protect scabs.

It was actually progressive Catholic clergymen who created the deepest crack in Duplessis’s reign, although he stayed in office until his death. During the 1949 asbestos strike, Montreal’s Archbishop Joseph Charbonneau ordered that churches across the city collect donations to support the strikers, proclaiming that “when there is a conspiracy to destroy the working class, the Church must intervene.”

Additional sources: La Croix du Mont Royal, Archives de Montréal, 2004; William Weintrob, City Unique, 1996.

2 comments

It’s not “January 6th 1693” as stated in your article, but January 6th 1643. Otherwise, he would have waited 50 years to carry it up the mountain…

Thanks Charles – I have now fixed this error in the text above. Sometimes I think I must have numerical dyslexia…