Montreal’s wastewater treatment plant can be found at the far east end of the island in Pointe Aux Trembles. It’s the largest in North America and ranks the third largest in the world- capable of handling 32 square metres of water a second. Raw sewage (usually) ends up here via a network of deep-level tunnels referred to as interceptors. These interceptors form a ring around the island, collecting and distributing wastewater to the plant before it has a chance to enter the surrounding rivers. To get a better sense of how the interceptors work, you can have a look at the entry I posted earlier on Undermontreal.

While it’s an impressive system in terms of its scope and capacity, the treatment process itself leaves much to be desired. In fact, it’s actually one of the worst in Canada. A national “report card” issued by the Sierra Club in 2004 gave the city’s treatment process a grade of F-. The only other city to receive a grade worse than Montreal was Victoria, a place which doesn’t even have a treatment process in place yet.

The biggest problem is that the plant only provides primary treatment of its sewage. Most other cities across Canada deliver secondary and even tertiary treatment of wastewater resulting in far cleaner water. By comparison, the effluent from Montreal’s plant remains full of pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, and a multitude of other contaminants. While this pollution is usually kept clear from the shores of Montreal, it inevitably ends up somewhere downstream of the island where the effluent has been known to be wreaking havoc with the river’s ecosystem.

Even during the era of its conception during the late 1960s, Montreal’s proposed treatment plant was deemed to be inadequate to solve the problem of worsening water pollution. Secondary treatment schemes were entertained, but the costs involved were considered too high for it to be considered feasible. Instead, the plan was to incorporate additional levels of treatment to the plant after it was completed, which at the time was expected to be 1981. It was thought that by then “cheaper and better schemes may be available.”

Montreal has always been behind the times in terms of sewage treatment. While much time and money was put into developing its large-scale collector sewers between 1920 and 1965, their contents simply flowed directly out into the open waters surrounding the island.

Baby Steps

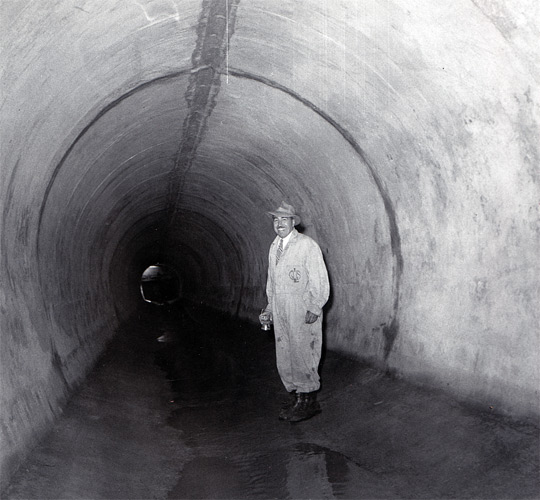

Perhaps anticipating future problems, in 1930, the Province of Quebec ordered that Montreal start treating some of the sewage flowing into Riviere Des Prairies. Shortly thereafter, Montreal began work on the North Interceptor. This 14 foot tunnel was intended to transfer sewage towards a site on Isle de la Visitation where it was thought that a local treatment plant could eventually be built. The interceptor was such a low priority that it took 25 years to complete. As for the proposed treatment plant, ground was never even broken and by 1967, plans for its construction were officially scrapped.

From Bad to Worse

For close to a century, Montreal could always rely on the swift-moving waters of the St. Lawrence, Riviere des Prairies to whisk sewage away from the island. However, by the 1940s, it was becoming obvious that this practice was no longer working as well as it had in the past. Public swimming areas around the island were being forced to close. The waters were starting to foul. Clearly, there was no way of hiding the fact that the practice of continuously dumping sewage into the open waters was causing problems. Still, it would take another thirty years before concrete steps would be taken to help remedy the situation.

By the 1960s, an average of 400+ million gallons of sewage a day was being discharged directly into the waters surrounding the island. By contrast, during this same period, Toronto was cleaning 98% of its wastewater using a combination of four treatment plants. Montreal couldn’t claim to match this percentage until 1996. It would be the last major city in North America to start treating its sewage.

Starting to Get Serious

In the summer of 1967, during the middle of Expo, mayor Jean Drapeau’s engineering department released a report proposing, not one, but two treatment plants for the island- one which could handle the north/east watershed and another for the south/west encompassing downtown Montreal. Over the next few years, much debate amongst the island’s communities took place involving where these facilities would be located, how much could be spent and when they might be completed. A site adjacent to the Victoria Bridge (previously used as a parking lot for Expo) was considered as was Isle St-Therese, but both were later shelved due to “environmental concerns.” Years would pass before a master plan was drafted.

It was eventually decided to build just one treatment plant in Point Aux Trembles and eventually use it to treat all the island’s municipalities’ sewage. Both the North Interceptor and the St-Pierre collector system would be incorporated into the plan- measures which city officials claimed would help save millions of dollars. Work finally commenced in 1974 with the expansion of the North Interceptor. It was expected that the system could be completed and functioning by 1981. Turned out they were about 15 years off the mark.

Sewerage Scandals

The website for Montreal’s treatment plant provides a timeline highlighting key dates in the construction of its treatment system. It’s a decent overview, but it conveniently leaves out all the problems encountered along the way. There are no indications as to why the project took close to twenty years to complete at cost of over a billion dollars more than the initial estimates.

To go through that history of problems in detail would take far too long for one blog entry, but one can get a sense of it all by reading through the newspaper headlines that appeared over the duration of the project.

1964 – “Sewage plant site Marked”

1967 – “Construction of wastewater treatment plant to cost $131,000,000”

1968 – “Roxboro residents warned: don’t swim in the Back River”

1969 – “Town of Mount Royal against city on new sewage plant”

1970 – “Clean air group claims sewage project ‘Waste of Money’”

1971 – “Montreal’s sewage treatment plan probed further by Quebec”

1971 – “Montreal to build $300,000,000 sewage disposal plant”

1973 – “Quebec tells Montreal to accelerate work on sewage system”

1974 – “Quick start to sewer plan urged”

1974 – “Pollution ratings close eight more area beaches”

1974 – “Montreal’s $500,000,000 sewage clean up”

1975 – “Executive committee seeks tender control”

1975 – “Quebec to pay half Montreal’s sewage bill”

1976 – “Economic woes threaten metro, sewage line work”

1976 – “Sewage plant, metro delayed”

1976 – “Is the Saint Lawrence an open sewer?”

1977 – “Province suspends sewage project”

1977 – “Sewage contracts stopped by Montreal”

1977 – “Costly sewer system simply shifts the problem”

1978 – “Back River Clean by 1986”

1978 – “Our sewage scandal: big plans but still little action”

1979 – “First phase completed of Montreal’s $1.2 billion sewage clean-up”

1979 – “$240 million sewer line awaits as city argues with suburbs”

1980 – “Time to take the plunger”

1983 – “Montreal wants Quebec action on huge southern sewer line”

1985 – “Dumping sewage into our rivers: there’s light at the end of the tunnel”

1985 – “Sewage pipe polluting 20km of river: experts”

1986 – “Boat will tour St. Lawrence sewer dumps”

1987 – “Push of button officially starts sewage plant”

1987 – “Montreal sewage plant called oversized, substandard”

1988 – “Not cleaned up yet”

1989 – “Waste spills into river after plant breakdown”

1990 – “Sewage plans running late, completion set back to ’94 by problems”

You get the idea…

Completion and Beyond

Finally, by 1998 all portions of the interceptor network had been completed and was being used to transfer most of the island’s sewage to the treatment facility. Being grossly over budget and over schedule, the original plan to introduce secondary treatment never came. Having already been considered obsolete during its conception, today’s plant is in dire need of upgrading if it’s to match the expectations of the 21st century. An announcement was made last year that Montreal would be seeking $200 million to help convert the plant into an ozonation treatment facility. The conversion would make it the largest city in the world to be using this more efficient process, but so far details have been vague and it’s questionable as to how and when all this might happen.

But despite the fact the existing plant is behind the times in terms of treatment, it does do an adequate job of handling large amounts of wastewater. As well, the large-diameter interceptors can usually accommodate heavy rainfalls, which means a lower percentage of raw sewage ends up in the rivers when compared to other cities such as Toronto. As a result, the water around the island is a great deal cleaner than it used to be— enough so that the water is now deemed suitable for swimming. While the number of recreational beaches on the island has dropped from over 20 in the 1940s to only two today, they can still be used. It’s better than nothing, I suppose.

In Part II: A Look Inside our Crappy Treatment Plant.

12 comments

Highly readable and interesting. Why does every construction project go way over budget, and be full of scandal? My father stopped working in Montreal 30y ago because he couldn’t stand the stink of the mafia.

My attention was diverted by the odd measurement, ” 32 square metres of water per second.”

Isn’t liquid measured by the litre?

Just nit-picking – but I wonder which is correct?

George: Yeah, I guess it does seem a bit odd now that I think about it. I just pulled the figure from a Gazette article published last year – http://www.canada.com/montrealgazette/news/story.html?k=9701&id=e01b646a-b20d-4d67-8e45-70e9ac096f94

Maybe they meant to say cubic meters? That would probably make (a bit) more sense.

It’s definitely cubic metres. Based on the tour I had there, I could see that being a fair number.

It’s not every construction project that goes over budget, just highly specialized engineering-type projects. This isn’t a road, condo or mall that has been built the same way 100s of times before.

Swimming in the river. They used to do that off Verdun, a particularly popular area was known as Leblanc’s Wharf which was at the bottom of roughly 2nd avenue. But then the polio scare of the 50’s kept my generation of kids out of the river. But it is something I think I might do one day before I die, just go in for a dip, what the heck….Today they say the river is much cleaner and I believe it but I still wouldn’t eat the fish.

Here is a link to a post over at Pruned some of you might find interesting called The Wetland Machines of Ayala.

http://pruned.blogspot.com/

The standard ‘scientific’ unit of measurement for flow of water is cubic meters per second – just like the ‘scientific’ unit for wind speed is meters per second. Clearly these units are not widely used by the general public.

As for project cost over-runs, this is nothing new, nor is it unique to Montreal. In fact, a consensus is starting to form that this may in fact be innate human nature: we are overly optimistic about things that we know and we tend to discount unknown factors too much. For large scale transportation projects (the field which I am most familiar with), the final costs tend to be 2-3 times the original estimates, and the ridership figures (for public transport projects) also tend to be over-estimated by a similar factor….

One reason for this consistent estimation bias (and it is consistent – it is not like we sometimes over-estimate the costs!), is that if we were more realistic, we probably would never start anything!

On the weekend,I discovered the Tail Race canal to the left of the École Secondaire Mgr Richard in Verdun, near the Champlain bridge access road. This originally was/is the water outlet of the Atwater Filtration plant. Can anybody give me some historical and present information on this canal. The old Petite Rivière St Pierre used to join this canal and continue west to empty into the river between Regina and Strathmore but ws covered when they made the Arthur Thérien Park. Also, the Grand Trunk Boating Club was situated on the Verdun side of the Tail Race canal wich also was/is the dividing line between Verdun and Pt St Charles.

Guy Billard

Société d’Histoire et de Généalogie de Verdun

Guy

Guy, as far as I can tell, the actual tailrace never extended further south than where Blvd. Gaetan Laberge is today. All the shoreline beyond that point was added during the 1950s. The extent of the landfill is evident Shortly before that time, the tailrace was covered and two large diameter sewers were laid in its place- one of which is known as the St-Pierre Collector.

The tailrace pretty much became obsolete when the plant stopped using water from the Aqueduc to power its engines. So the canal we see today was added more as a discharge channel for these two sewers than an actual tailrace for the Atwater plant.

There is a small overflow tunnel that runs between the plant and the St-Pierre Collector, but I don’t imagine it gets used too often.

As for the original tailrace, if you want to get a better sense of its history, your best bet is to have a read through Thomas C. Keefer’s reports:

http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=keefer%20AND%20mediatype%3Atexts

Wastewater contains high levels of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus which can be very harmful in large doses. Nitrogen is removed by oxidation which converts it to nitrate and then into nitrogen gas which is removed from the water by releasing it into the air.

FyI :

The term 32 square meters per second is correct. They are not talking about volume though, but a flow of mater that passes through a certain dimension per second.

It’s related to the volume, but in design of systems like this, it’s much more pertinent to design for the flow then the volume.

If you’re wondering, if I’m not mistaken, it comes about to 9 m3/s on rainy days.