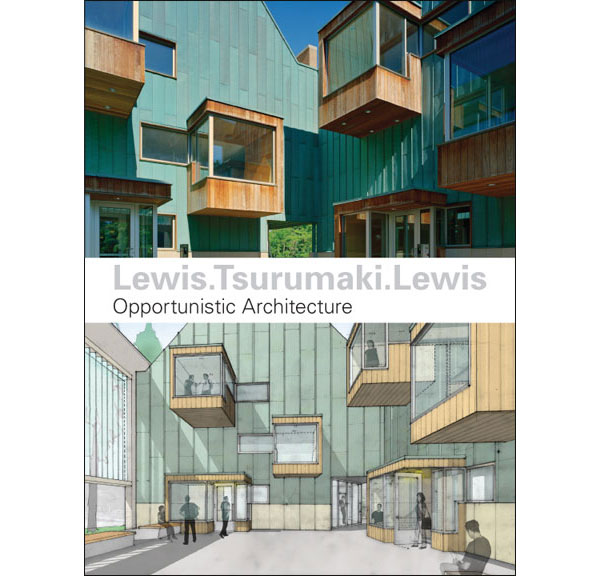

Authors: Paul Lewis, Marc Tsurumaki, David J. Lewis (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008)

The world of design is seemingly growing on a daily basis to (rightfully so) take into account all the different scopes that the term “design” can take. As I’ve read through more and more books – design related or not, fiction or non-fiction – I am discovering an interesting trend, and that is just how deep the roots of design run.

As a student, I was constantly told that “design is a universal language” and it wasn’t until my final year of school that I completely grasped this concept. In their book Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis: Opportunistic Architecture, LTL (a.k.a Lewis, Tsurumaki and Lewis) talk to a philosophy of architecture which was introduced on the very first line of the leaflet in the book, stating, “What if the constraints and limitations of architecture became the catalyst for design invention?” Their sole belief, which they uphold throughout, is that the tighter the constraints, the more interesting, thought-provoking, and innovative a design can be…..eerily familiar to what I had been hearing for the past four years of schooling.

Beginning with this philosophy, the book then moves through their projects in alphabetical order—not drawing attention to an particulat time while allowing the projects to speak for themselves, like small exhibits. This format worked wonders for the book. It was easily accessible, allowed me to read through a few sections and put it down without a worry of being bogged down by page upon page of information regarding a single project.

Speaking to the structure and format of the book, they did a masterful job at filling every page (while maybe not visually and more psychologically) with all the content one would need to understand the where, the why, and the how of each project. I was never wanting for more information, and felt completely satiated when I flipped a page and read the heading for the next project.

The style that they impose on these pages is also something that they talk about at the end of the book as one of their “Tactics for Opportunistic Architecture” (of which there are five). They reference the battle which has been raging for centuries over how to (re)present the visual world, using technology versus hand drawings. It is argued that since the invention of computer programs that have allowed us to visualize ourselves completely within a space of photorealistic quality, the true beauty of design has been lost due to the reduced focus on hand drawings.

I have long argued that there is a place for both and that they can and should both be incorporated in different ways within any particular project. As such, I was delighted to see that LTL shared my enthusiasm— employing beautiful renderings of their projects with a perfect mix of hand-drawn perspectives, technical drawings, and “process” sketches.

As I moved through the works, however, I found myself having a slight mental battle with the terminology of their philosophy. For instance, the book and philosophy itself are entitled “Opportunistic Architecture,” and while there are several samplings of what one might consider traditional “architectural work” (new construction, façade design, large towers, city infrastructure change or master-plan style designs), there are also many instances where other forms of the design world creep under the umbrella of “Opportunistic Architecture.”

This happens to such a degree that at times, the philosophy itself, reads as merely a handout I received in school for my duties as an interior designer. “How do you design a space in which you are given a box, a limited scope of parameters and programmatic details (budget, client, site, etc.) and turn it into something amazing?” The basis of this philosophy is that one must look at the functions and program, using these problems to push users farther into creative and rational thought. In essence, using the “opportunities” one receives and making the best of them.

While this is all true and I agree with every word of it, throughout the book, the authors make no reference to the interior design, industrial design or even graphic design works that are clearly important elements with the projects they work on in their office. They specifically show, for example, how they hand fabricate pieces for certain interiors and, to me, this speaks much more to industrial/interior design than it does as ‘architecture’—that, in the most common sense of the term, focuses on the design of building-scale structures.

I am not one to campaign for the segregation of schools of thought and, in fact, rejoice in the fact that LTL has done such an amazing job at pulling all of these facets of design together since it may be one of the single most important issues required to create meaningful environments. However, if design is a universal language, which it has proven itself to be time and time again, then how and why would one simply refer to it under one name?

With this in mind, had LTL used a more inclusive language—allowing designers of all scopes to join underneath their philosophy and learn more about what each other are practicing—it would have gone a long way to furthering the ideas that LTL purveyed in Opportunistic Architecture. Had they mentioned the other design disciplines even only slightly, I believe it would have substantiated their philosophy drastically with a larger market of support from all disciplines—raising the awareness to what designers of all names and professions around the globe deal with daily, in their pursuit to make some (hopefully) positive impact on this world.

Overall, however, Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis: Opportunistic Architecture is a smart and engaging book. One that does not allow for much time to let it out of your sight, thanks to the wonderful structure and powerful story behind each project. The passion they have for their work is evident in the quality of each project and it is for this reason that a designer, like myself, cannot help but want to see everyone united under a banner such as theirs.

***

For more information, visit the Princeton Architectural Press website.

**

Jeremy Senko is happily lost in the world of theoretical architecture and design. He is forever a student at heart, consistently reading, experiencing and learning about the world he inhabits. More specifically, he recently completed his Bachelor of Interior Design at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, where he pushed the limits (and the patience) of his professors.