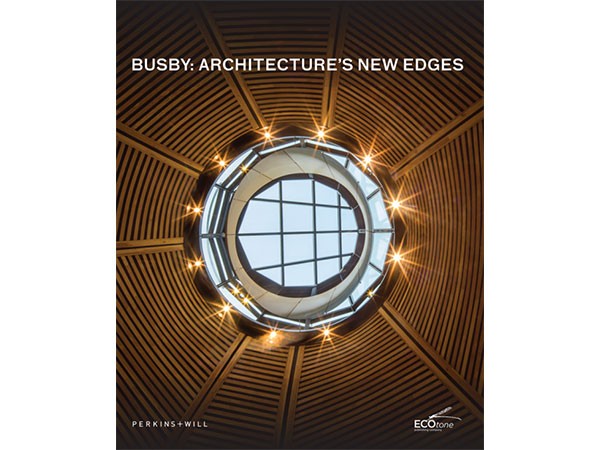

Centuries from now, when historians look back to the beginning of the Anthropocene, a time when we realized that human beings had become the dominant influence on living systems, we will be particularly interested in what is happening at this time: a burst of design, technology, and social awareness coming together led by a particular sector of the population: architects, builders, redevelopers, and resilient urbanists. Far ahead of any other profession or industrial sector, architects and designers, planners and developers, all inspired by farsighted cities, are reimagining the relationship between human systems in their work. Architecture’s New Edges traces the beginning of this era through the eyes of one of its foremost practitioners, Peter Busby.

– Paul Hawken, from the book’s Foreword

A few years back, while writing about one of Peter Busby’s newly completed projects – the Centre for Interactive Research in Sustainability (CIRS) at UBC – I remarked that we had come to a point in human history where our relationship with the natural world was now an everyday part of our global conversation, that even young children were becoming aware through popular culture of the phenomenon of global warming, climate change, or whatever nomenclature was introducing it to them at that time. Perhaps no other movement, with the exception of the industrial revolution, has had such a profound impact on our built world as has the environmental movement, and it is no secret that Peter Busby and his design philosophy has been both an influence, and influenced by it, for the past three decades.

And so it is very much in this vein that Mr. Busby offers us here his new book, Architecture’s New Edges, encapsulating his firm’s overall philosophy, supported with numerous case studies and innovations from his office’s early days, up to some of his most large scale projects to date, realized now as part of the larger multi-national entity of Perkins+Will. A juggernaut on the world stage of architecture, rubbing shoulders with the likes of AECOM, HOK, and Gensler, this new larger format for his practice has provided him the opportunity to spread his wings in a way which was simply not possible before.

For the foreword of the book he has selected Paul Hawken, co-author of the seminal Natural Capitalism, which, when it first appeared in 1999, introduced the popular modern concept of “externalities,” suggesting that contemporary capitalism was erroneous in its omission of the planet’s living systems from its logarithms and business models. It has not gone unnoticed that in just the space of fifteen years, this form of doing business is now being increasingly scrutinized by large populations in numerous cities, especially after only just recently emerging from the catastrophic effects of the 2008 global recession.

In contrast to the petroleum industry or business on Wall Street, the world of building construction has made leaps and strides towards a more sustainable business model in the past decade. The dramatically lowered capital costs of renewables such as photovoltaic cells will most certainly have lasting impact on our global footprint, and it remains to be seen at the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris how serious the politicians have taken the demonstrations we’ve seen in the run up to the event, such as the People’s Climate March that took place last year, where millions around the planet took to the streets to make sure their representatives got the hint (400,000 people turning out for just the NYC march alone).

With the stakes now as high as they are, the timing of Mr. Busby’s book couldn’t be more appropriate, and as such has been framed to speak to the social responsibilities we all have for sharing this planet. The first two sections of the book are then aptly named Social Responsibility and Corporate Responsibility, revealing how the office strives to practice what it preaches and then some. For as Peter points out early in the book, an architect needs to care about more than just a finished building – they are also responsible for how the building fits into the bigger picture, how it takes its place in the city now and in the years to come, the materials used to construct it as well as the resources it will use over its life-cycle. Even the architecture methodology employed in its design is part of this larger picture, and so it has been for Peter’s practice over the years, in all its incarnations, big and small.

It is in the next chapter of the book – Culture of Innovation – that Peter is able to effectively demonstrate the transformative influence of not just his firm’s designs, but design in general. As such, it includes various examples from his office ranging from the innovative wood and steel composite structure of his award winning Brentwood Skytrain station, to master-planning a new community for 30,000 in Edmonton on the site of that city’s former municipal airport. And much like other large architecture firms have encouraged their designers to innovate new details and systems to suit their buildings, so too does Perkins+Will. Called the “innovation incubator,” for the last five years the firm has promoted an internal idea development program, nurturing young talent by giving them paid time to develop their ideas. Recipients compete with each other within the larger firm, with 16 grants awarded every year.

Busby’s biggest contributions to the conversation of how we can build more responsibly, however, occurs within the next two chapters – Whole Systems Thinking and Regenerative Design. While the technical explanations of each are not without their challenges, two case studies illustrate their concepts such that even a non-architect can grasp their significance. The first, Dockside Green in Victoria, presents whole system thinking in the form of a 15 hectare community built on an old waterfront brownfield, intended to exist within its own ecological footprint. Initiated in 2005, and continuing to be developed to the current day, its biggest sustainable component is an on-site biomass plant, converting local wood waste into energy for the community’s heating and hot water. All grey and black water is treated on-site, using natural irrigation processes, with rainwater also collected and treated on-site.

The next section on regenerative design raises the bar by going beyond the question of how we can live within our means to ask how our built environments could contribute to the future, how buildings could cease to be huge consumers of carbon, clean water, and other natural resources, and instead provide a means to replenish these forms of natural capital. It imagines a world where buildings, like trees, could live in a symbiotic relationship with people. The CIRS building mentioned earlier provides a perfect example of such a building, demonstrating numerous strategies by which a building developer could realize a more environmentally responsible project, from green walls and carbon sequestration, to solar arrays and heat waste recovery.

The final two sections of the book provide a glimpse of the future, with The Future of Cities providing several case studies in which Peter has had a hand, from the Abu Dhabi 2030 Plan to the Marine Gateway development nearing completion in south Vancouver—one of the largest transit-oriented developments the office has realized to date. Other Smart City projects include the removal of outdated transportation infrastructure, including the demolition and remediation of the land currently occupied by the Gardiner expressway in Toronto and the Georgia Viaducts in Vancouver.

The final chapter of the book, The Future Face of High-Performance Design, features three of his most recent projects, including the multiple award winning VanDusen Botanical Garden Visitor Centre, the Earth Sciences Building at UBC, and the previously mentioned Blatchford Development in Edmonton.

As the book makes explicit, society’s view on climate change has warmed and cooled since the 1990’s, when the conversation first began. Even LEED has had a rough time, with right-wing politicians often citing it as a waste of public money. And it is no secret that LEED isn’t the only vehicle to certify one’s building as environmentally responsible. Passive House and the Living Building Challenge are but two new kids on the block, giving LEED a good run for its money in a decade that has seen the emergence of the term “greenwashing” — where buildings over promise and under deliver in their sustainability performance.

Overall, Architecture’s New Edges take its place as both a formidable monograph of Peter Busby and Perkins+Will’s work, as well as a testament to the radical paradigm shift we currently find ourselves in the midst of, whether our politicians and their corporate supporters are willing to acknowledge it or not. Much like factories and electrical substations emerged in the time of the industrial revolution, our current age is moving towards buildings with a smaller carbon footprint — perhaps with our municipally enshrined compost and recycling collections standing as a simple example of this shift. This process is all the more evident as our summers get hotter and our forests get drier. And with the public outrage against VW and its deceitful emissions software only now begun, this alone could prove to be a straw that breaks society’s tolerance of unregulated global capitalism… or what Paul Hawken refers to in his foreword as an outdated plutocratic regimen of “human ignorance and rapacity.”

The message that Peter Busby wants to leave us with here, then, is meant to inspire us, particularly with respect to the social contract of the architect:

“We can make healthy, productive, and safe environments; we can heal people and nature; we can nurture education; we can house the poor. We can add to, rather than waste the earth’s resources. In short, we can enrich all facets of the public realm. All of this is our responsibility as architects, as we are agents of social change. We can only measure and respect great architecture if it does all of these things, well and at once.”

***

Sean Ruthen is a registered architect and writer, currently serving his second term on Council at the Architectural Institute of BC.