Author: Shaun Fynn (Princeton Architectural Press (2017)

More than sixty-five years have passed since Le Corbusier was commissioned by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to fulfil the role of architect and planner for Chandigarh. A bold experiment, Chandigarh broke from tradition to define a new vision for the future of urban living and became one of the twentieth century’s most powerful expressions of modernism.

The origins of Chandigarh lie in the 1947 Partition of India, which divided the state of Punjab between India and the newly formed country of Pakistan. Lahore, the former state capital of Punjab, was now situated in Pakistan; therefore a new administrative and political centre was needed to govern the Punjabi territory that remained in India. A sparsely inhabited area of the plains within clear sight of the Himalayan foothills was chosen as the site for a planned city of half a million inhabitants, Chandigarh.

- Shaun Fynn

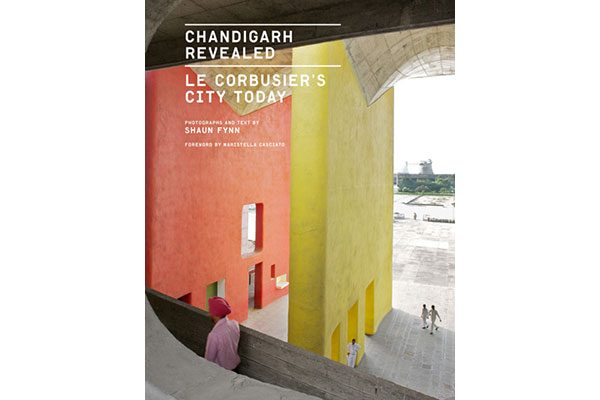

In 2016, over fifty years after its inauguration, the Capitol Complex of Chandigarh was named a UNESCO World Heritage site, along with several other projects by the Swiss-born French architect Le Corbusier. In Chandigarh Revealed, UK born designer and photographer Shaun Fynn has captured the spirit of Chandigarh—giving us an honest portrayal of the contemporary city through his camera’s lens, complete with essays on the city’s political and urban planning history, and providing us with a rare glimpse into how the city has fared in its first half century.

As a resident of Chandigarh, Fynn had unprecedented access to the city, enabling him to photograph and document its day-to-day existence, warts and all. With the concrete around the Capitol Complex government buildings now weather-stained, Fynn at times opts for black and white photography to capture the delicate shades of the material’s half century patina. The book also includes in its closing pages an interview Fynn conducted in 2015 with M. N. Sharma, Chandigarh’s city architect from 1965 to 1979, and who was an associate of Le Corbusier’s during the city’s inception and construction.

With an introduction by Maristella Casciato, senior curator of architecture at the Getty Institute, the main event of the book is its visual cornucopia, as shown through Fynn’s camera lens, who captures everyday life: stacks of papers in the offices of the city’s commercial sector, juxtaposed with black and white images of the Legislative Assembly. With an astonishing 266 photos contained in its 240 pages, the book is a visual tour de force of what many deem to be the architect’s greatest work. The book also includes in its credits the school of architecture at the University of Chandigarh, from which much of the research that went into its production originated.

It goes without saying that Le Corbusier was given the commission of a lifetime with Chandigarh—the complete masterplan of a city, including government, religious, commercial, and residential buildings. This also included detailed design down to the scale of the manhole covers, each of which depicts a map of the city. The book also provides us with the names of his associates, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, as well as his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, all of whom lived in the city for fifteen years until it was finished. Le Corbusier, himself, spent two months a year there until the main government buildings opening in 1964.

While Fynn points out that much of the city—the housing, especially so—was realized by his associates, the Capital Complex was completely designed by Le Corbusier. Including the Secretariat, High Courts and Legislative Assembly building, he sited the complex between the city and the Himalayan foothills to the east. Of these three buildings, the Assembly (which is also known as the Vidhan Sabha) is thought by many to be not just the highpoint of Le Corbusier’s career, but one of the greatest buildings of the twentieth century.

With the three colours of the Indian flag predominant in the Assembly’s interior—along with the building’s entry and the exterior of the High Courts—the civic complex provides us with a visual record of much of the architect’s philosophy, including his ability to adeptly assemble a group of buildings on a site. Equally powerful is its extensive use of brise-soleils fenestration to provide cross-ventilation and natural light. Chandigarh is also home to the Open Hand sculpture, which he designed as a symbol for the city in contrast to the closed fist, and has become (along with the Modulor) one of the architect’s most poetic designs.

The visual material in the book is broken into four sections, each corresponding to specific functions of the city: The Capitol Complex; Health, Education and Recreation; Housing; and Commercial and Civic Centres. In some instances, Fynn’s lens has not flinched from some less than flattering depictions, including the urban decay in Sector 17—the city’s once vibrant commercial heart—which is faltering due to the construction of new shopping malls on the city’s periphery.

There are only a handful of instances in history where an architect has been given the task of master planning an entire city, with Oscar Niermeyer’s plan for Brasilia being one of a few other notable examples. Given the strict current compartmentalization of municipal planning departments from the professions of architecture, planning, and landscape architecture, it is hard to believe that projects like Chandigarh were created at all. Perhaps for this reason more than any, it is Fynn’s view that it can teach us some invaluable lessons: demonstrating to some of Le Corbusier’s most brutal critics that the architect’s ideas about urban planning were not only realizable, but could accommodate future transformation, as the city originally designed for half a million inhabitants is now home to over one million.

And while this book may not change the minds of those who believe Le Corbusier is responsible for the car-driven urban planning and Brutalist concrete buildings we see in cities around the world, it is as close as we come to a complete and realized urban design of not just Le Corbusier’s vision, but the mission of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) to build socially responsible urban spaces. In the case of Chandigarh, the architect created a visual language for the city’s new identity, one devoid of any British colonialist iconography.

Overall, Chandigarh Revealed is a frank and honest portrayal of this city. It is a wonder to behold, pointing out that while Chandigarh is not perfect, it is as close to the ideal as could be given its volatile mixture of religion, politics, and geography… all orchestrated by an architect whose vision of how order could be achieved helped to shape the modern world and all that would follow.

***

For more information on Chandigarh Revealed, visit the Princeton Architectural Press website.

**

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.