Planning Goals and Objectives – Shortcomings

The usefulness of the methods and techniques described in Common City Planning Initiatives revolves around the fact that they generally avoid the challenges associated with outlining, critically analyzing and evaluating specific objectives and goals related to the built environment.

Let’s ask a basic question: why are goals and objectives even needed in city-wide planning? Simply put, they offer targets to be attained, ensuring that all efforts and actions are put towards a specific, explicit purpose. Although one may rightly argue that city-wide planning efforts, to some degree, have been undertaken without much by way of explicit goals and objectives since the early days of cities, the growing complexity and interconnectedness of contemporary city systems—and the great implications of poor city planning—make them now necessary.

In pursuit of making planning easier, however, the development of objectives and goals in the recent past share many common shortcomings:

- They are too general: Frequently, goals and objectives are so general that few could object to—let alone discriminate between—them. A couple of examples from the City of Vancouver’s recent City-wide Plan Policy Report will serve us well here: “Improving public amenity provision and cultural vitality” or “Enhancing sociable and safe places for people and vibrant livable, well-designed neighbourhoods and shopping streets” What is meant by “improving,” “vitality,” “enhancing,” “vibrant” or “livable” and “well-designed” is left to the imagination. This type of language does well to make people think that good is being done, but in reality does minimal to allow people to meaningfully discriminate between different alternatives.

- They are too specific: On the opposite end of the spectrum, goals and objectives are often too specific and prescriptive: “all sidewalks are to be 36 inches wide” for example. Although these types of statements relate directly to transforming the city, the more general motivation behind them remains unknown. Why 36 inches? This serves to limit the innovation and the exploration of design and planning alternatives that can meet the same underlying intentions in different ways.

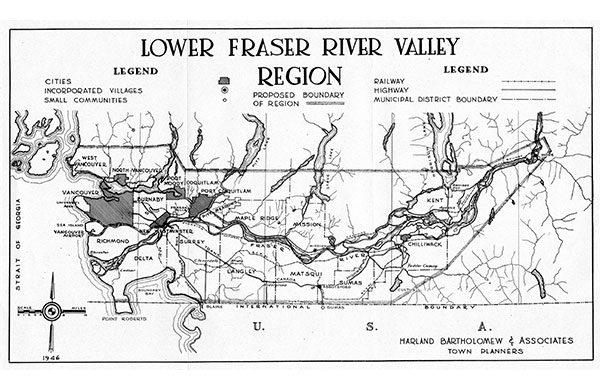

- They are irrelevant or unrealizable: Other objectives may be impossible to achieve. For example, the City of Vancouver’s goal of “Making connections to the metropolitan region and Cascadia” is well-intentioned, but beyond the means of the City since it crosses not only municipal and regional boundaries but international ones. Goals like this—that are outside the governance of municipalities—are commonly used to safely ‘pad’ the list of planning objectives since any attempt to evaluate their success or failure is impossible.

- They are too narrowly defined by few individuals: Some goals are narrowly motivated by the values of a few people who implicitly ‘force’ them upon the wider community. An everyday example is when pressures from developers result in the (re)zoning of an area of the city solely in the interest of short-term profits. This also has a long history in being used against marginalized groups who have little or no political voice.

- They are too short-term: Time is a very important consideration for city planning since a city can theoretically ‘live’ indefinitely. Humans generally don’t seem to be well equipped to deal with very long time frames and this is often reflected in city planning goals and objectives. A 100-year plan is all too rare, let alone a 200- or 500-year plan. Yet, many aspects of the city can, and do, last centuries. The street structure of ancient Rome, for example, can still be seen in the contemporary city. Ultimately, it’s easier for goals to deal with immediate or short-term challenges, the result being plans and objectives that are quickly outdated. Needless to say, any contemporary city-plan worth any merit will critically consider that its effects will well outlive its creators and anticipate continual change. I’ll specifically address time and its relationship to city-wide planning later in this series.

- They are not comprehensive enough: Although this is cuts across all the shortcomings listed above, sets of goals and objectives related to city-wide planning are typically far from comprehensive. The increasing complexity and systemic nature of modern cities makes the creation of a ‘complete’ set of goals and objectives that much more difficult. This being the case, although certain goals and objectives may be very rational, successes are countered by failures: the creation of a more ‘liveable’ community comes with increasing unaffordability, for example.

The overall result of the above is, in the words of Lynch: “…solutions that are irrational, or sub-optimal, or vague, or determined by a few spoken criteria for which the stated objectives are simply camouflaged.”

So, how are we to approach the creation of goals and objectives that avoid these shortcomings? This will be our focus in Part 4.

***

In case you missed it:

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 1

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 2

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 4

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 5

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 6

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 7

- Planning City-wide: A Primer – Part 8

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.