“In so many ways this has been a lifelong project. Some of my earliest memories – learning to ski at Sunshine Village, in Banff, seeing Jasper through the windows of a VIA Rail car, and stopping at waterfalls on family road trips across the Icefields Parkway – inform, somehow, each of the pages here. I recognize the hardworking design team behind each architecture and consultant firm that translated drawings into architecture, along with the builders that worked on challenging sites and in tough climates (and oftentimes with new materials and construction systems), the landscape architects who integrated the houses into their sites, and the engineers who resolved complex technical demands with poetic effect.”

- John Gendall

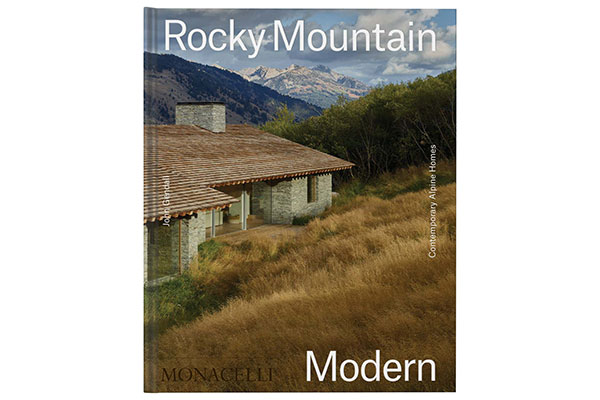

Author: John Gendall (Monacelli Press, 2022)

It is often rare that a book about opulent mountain homes can strike a sublime note, but that’s certainly the case here with this latest publication in Monacelli’s long-standing Modern House series. While modern houses in places like Martha’s Vineyard or the Hamptons take on more of a Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous sensibility, Rocky Mountain Modern: Contemporary Alpine Homes arrives more presciently, certainly given the devastating 2024 Jasper wildfire alongside other conflagrations that have recently made the news.

What was once the simple Henry David Thoreau desire to build a quiet place of one’s own away from the hustle and bustle of the city is now complicated by the reality of annual wildfire seasons—realities that may limit the number of new homes like the eighteen featured here. And while these are not humble cabins, the obvious draw to the breathtaking surroundings is on full display throughout the two hundred-plus pages, where the architecture of the houses themselves occasionally rises above the unbelievable landscape they are situated in (and fully gaping at).

Opening with a history lesson, Gendall tells us of a special guest who attended a 1945 city council meeting in Aspen, Colorado. For Walter Gropius, then head of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and Architecture, this sleepy Rocky Mountain town was looking for a new direction, and Gropius provided the modern blueprint, quite literally, for the town’s future layout, complete with housing aesthetics.

As depicted in the book’s opening map of the eighteen houses, each is a vertebra in the three mountain chains running from the southwest US to the Canadian Pacific Northwest. From Golden, British Columbia, to Golden, New Mexico, this geography of over 1500 miles provides its own regionalism, which Gendall points out has its own unique spin on modernism—known as the Rocky Mountain West.

A long-lost Frank Lloyd Wright building completed in the early 1910s in his distinctive Prairie style, just outside the Banff town centre, laid the groundwork for this distinctive style, with local materials on full display in a new tectonic expression. Several houses featured here, including the McLean Quinlan-designed home on the book’s cover, opt for a similar rugged exterior expression, with stone walls and a wood roof.

Given that Wright’s Banff structure has since been demolished—overrun by nature—it is a stark reminder that the Rockies are just that, cold and rocky, and that creating a homestead in such a harsh environment is not without its challenges.

Fittingly, while the book’s cover foregrounds mountain drama, the opening spread depicts a quiet green meadow, absent of architecture. This is a subtle nod to the Rockies’ diverse character: not just rugged, snow-peaked mountains, but an undriven land—even at times, arid and desert-like, with this latter environment on full display in the homes featured here by Rick Joy and Olson Kundig.

With both Aspen and Denver representing one response to Bauhaus modernism—they have recently added a new art museum by Shigeru Ban and a contemporary art museum by Adjaye Associates—Aspen is best perhaps known in the architectural community for a 1949 temporary tent structure design by Eero Saarinen, which galvanized modernism in the town’s art and culture scene.

Perhaps less known is an unbuilt house designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1937, to have been located in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. With Rocky Mountain Modern featuring three houses in the same area, the Resor House was Mies’ first commissioned work in the US. It would be ten more years before he realized his first built commission in America, and seven years before Gropius would arrive in Aspen and declare they should ‘build Modern’.

With precursors to both the Barcelona Pavilion and later Farnsworth House, the Resor House drawings are included in the book’s introduction (and are also on permanent display at the MoMA), the influence of which is clearly seen in many of the houses featured in the book. Strong horizontal lines in the plinth and roof, supported on slender columns interspersed with large vertical slabs providing shear walls, with plate glass to take full advantage of the surroundings, sound like the Barcelona Pavilion or Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, but it had its germination in Jackson, Wyoming.

Of the houses in the book, one in particular, known as the 5280 House in Bozeman, Montana, follows closely in Mies’ footsteps. Designed and built by its occupant, Frank Barkow of Berlin-based Barkow Leibinger, it’s one of the more Spartan of the houses featured in the book, designed with rough-sawn lumber to match the rural context, but stylishly modern enough in its up-to-date interior fittings that it doubles as both office and private residence.

Barkow cites the Resor House as his inspiration, with its bones constructed in wood instead of steel, something he would’ve been exposed to during his time studying architecture at the University of Montana.

For as Gendall points out in his introduction, another watershed moment for the Rocky Mountain West was when Richard Neutra came to the University of Montana to deliver a lecture in 1949, making connections there and eventually getting local commissions, including that for the Mosby House that has become a symbol of modernism in that part of the Rockies (and currently an Airbnb).

Among the many photogenic projects here—captured in award-winning photography—I was glad to see MacKay Lyons Sweetapple alongside other great firms. Notably missing are some of the great Pacific Northwest modernists (with Seattle represented but not Vancouver), from the Patkaus onwards. For those, I would recommend Reside by Clinton Cuddington and Michael Prokopow—soon to be the subject of a future Spacing book review.

And though many of the houses here are what one would expect given the caliber of the firms selected, what was most unexpected was to learn that the featured Rock Home in Canmore is the first of forty-four more to be built there. Called Carraig Ridge, the 550-acre private development has been master planned with all the architects working in a modern idiom. Walter would be proud!

And whether this lifestyle and architecture is your cup of tea or not, there is no denying the sublime beauty of the Rocky Mountain landscape, especially if one can turn their chair around and look at it. From snow-capped slopes to open foothill plains, these projects continue a long tradition of building with, and sometimes against, the great outdoors. Through plate-glass expanses or more sheltering forms, each home strikes its own balance of efficiency, comfort, and environmental engagement.

All the architects featured here are alchemists of space, crafting places that will resonate and reverberate in the landscape until Nature reclaims them, as it did for Wright’s Banff pavilion. Until then, this book is a roller coaster ride through the Rockies, a journey readers will be most certain to enjoy!

***

For more information on Rocky Mountain Modern, go to Phaidon website.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect.

One comment

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all people you actually understand what you are talking about!

Bookmarked. Please additionally consult with my web site =).

We could have a link alternate contract among us