Reclaiming Spaces/Places is an ongoing series written by Lacey McRae Williams that shares stories of Indigenous resurgence through public art and planning across Canada, Turtle Island (North America).

I would like to introduce two themes that are continually a point of contention in my own mind that I feel need to be discussed more often, with more people and to a deeper degree: 1) the city as a visual narrative of time and place, and 2) significant historical site selection, which includes the means of commemoration and preservation.

The following artist’s work reevaluates these ideas and shares voices that are less likely to be heard in a contemporary public realm; voices of the Anishinaabek, one of the First Peoples to inhabit areas of Ontario pre-contact.

I met Jimson Bowler at the One of A Kind Show in Toronto, March 2014. He had his art on display alongside a hand-selected group of Indigenous Artists as part of the Thunderbird Marketplace. Jimson’s art at the show was a combination of contemporary sculpture, silverworks, jewelry, and painting. Having been inspired by Norval Morrisseau myself, the grandfather of the Woodlands style of painting, I was instantly drawn to Jimson’s provocative, political, and revelatory works. After a few minutes of talking with him, he explained that all of his pieces are constructed from reclaimed materials found in Ontario, adding depth and meaning to each one. Each piece tells a unique Anishinaabek story – of creation, belonging, survival, community, and spirituality – emphasizing the extreme need for all persons to connect to place. He blends traditional Woodland’s line and shape work with a contemporary streetart-esque technique to reclaim visual space otherwise conquered by colonial values and perspectives.

He notes, “My inspiration comes from the Peterborough Petroglyphs, using the story of the anishinaabe/trickster/nanaaboozhoo as teacher lessons and stories… My sculptural work combines traditional mediums such as bone and turquoise with discarded modern materials. I take inspiration from the traditional ways that respectfully use all materials from mother earth and I seek to create objects that keep the stories alive, motivate us to learn the culture and realize that Aboriginal people are not relics of an ancient past.”

To explore these ideas further in his work, I have chosen to highlight two public pieces that exemplify notions of reclamation, resurgence, and the importance of place.

‘Big Loon Portage’ depicts the 5000 year-old Anishinaabek Chemong story represented in a modern-day setting. This bus-wrap in Peterborough was selected by Artspace as a part of their ‘Art is Everywhere’ initiative. Jimson’s submission was selected from 22 artists to make its way through the city like a big canoe. The canoe is one of the many iconic symbols of Peterborough and Canada at-large, but more than existing as a symbol encased in traditional history and locked away in a museum, this piece creates a wonderfully layered metaphor as it navigates Peterborough’s city streets. The bus is transformed into a canoe – its wheels the paddles, its roads the rivers, and its daily commute the larger migratory journey. ‘Big Loon Portage’ invites an intricate public discourse on the modes of transportation used across space and time while reflecting upon the sentiments of belonging and community.

The public transit of the Chemong story addresses the first theme mentioned above – city as a narrative of time and place. It does so by interjecting a highly visible traditional Indigenous world-view on top of a classical Eurocentric depiction of landscape, and into our modern colonial world. This image travels through Peterborough sharing the story of the people who first inhabited the land, while welcoming viewers of all backgrounds and beliefs to partake in the contemporary narrative.

“I know of no other stronger image in this town than the canoe, or a better way to honour the people than together.” – Jimson Bowler (Source: www.trentarthur.ca)

The second example of his work that exists at the confluence of urban planning, public art, and Indigenous resurgence is the piece he calls ‘Place at the End of the Rabbits’ a playful appropriation of ‘Place at the End of the Rapids’ or Nogojiwanong in Anishinaabemowin. He combines multiple paintings hung outdoors with petroglyph public art, and artistic signage to commemorate and celebrate Anishinaabe perceptions of place. This is particularly interesting from a heritage standpoint, addressing the second thought-hurdle mentioned above – what we tend to view as significant at any moment in time.

Now I know this is not a new topic, and many municipalities and organizations struggle with determining what is historically significant, how significant it is (listed versus designated classification for example), and how it shall be preserved or commemorated. But to provoke some alternative streams of thought on this topic, think about a history book. The books we read in Social Studies in elementary school, we read as fact. The explorers, the fur trade, the War of 1812 as examples, shaped our perceptions of our society over time. We’ve since learned and are continuing to learn that many facts were missing, providing us with an incomplete and heavily glorified story of our past. Let’s translate these stories into our daily commutes throughout our cities. Which stories are being shared visually from generation to generation, influencing our perceptions of the places we live, work, and travel to?

What are we remembering as significant?

Is it art deco buildings, distillery districts, and Victorian neighbourhoods?

Or is it burial sites, Indigenous place names, and cultural trails?

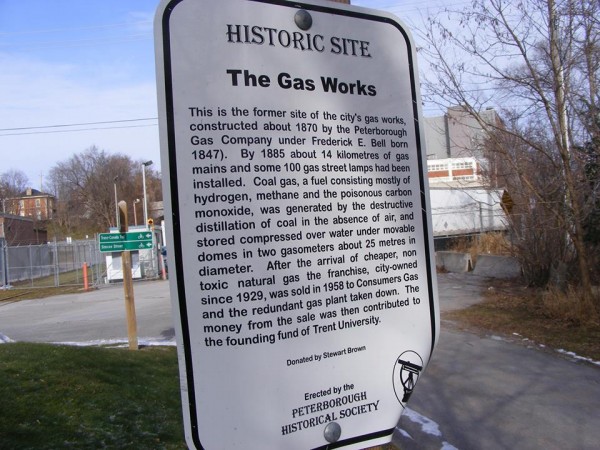

The images below speak to two very different versions of heritage commemoration, highlighting the chasm between Western and traditional Indigenous worldviews.

Source: www.jimsonbowler.com

Source: www.jimsonbowler.com

Jimson’s work reclaims these spaces and places by transcending time, overlaying the past on the present, and the present on the past, reminding us of our wholly complex and layered history. His work reinforces the need to embrace and celebrate the Indigenous legacy alongside the colonial one.

This series has been heavily influenced by the many talented, determined, and wise indigenous activists, artists, academics and friends who ignite a fire in me to dig deeper into our true history, recognizing colonialism is still pervasive today, and to take steps to decolonize a practice I have been privileged enough to belong to.

A huge thanks to Jimson Bowler for taking the time to share his stories with me.