The Ottawa Curling Club

On October 18, I will be giving a walking tour through Sandy Hill and Lowertown that explores the social history and politics of play in Ottawa. This post offers a taste of the kinds of things we will discuss on the tour by looking at another local play space, the Ottawa Curling Club. For more information about the tour and to buy tickets, visit the Ottawa (de)tours website.

***

In early June, I took advantage of Doors Open Ottawa to visit a few of the city’s hidden treasures. Stops on my itinerary included the rooftop garden at the C.D. Howe Building on Queen Street and the “other” Library of Parliament housed in the Old Bank of Nova Scotia Building on Sparks Street. The highlight of the day, however, was the Ottawa Curling Club (OCC) at 440 O’Connor Street.

Without the Doors Open map, I might not have found the OCC building. It sits on a stretch of O’Connor between Argyle and Catherine that feels rather desolate. More noticeable is the constant stream of impatient drivers spread across too many lanes of traffic as they wait to access the Queensway and the imposing tower of the Taggart Family Y on the east side of the street.

Built in the Edwardian Style with a hint of Beaux Arts, the Ottawa Curling Club is of a piece with other civic buildings from the turn-of-the-twentieth century. The red brick with white accents will be familiar to local residents. It is only the club crest, which consists of two curling brooms of red and gold crossed over a red curling rock with the club’s initials at the brooms’ intersection, that distinguishes the three-story structure.

As part of Doors Open, the OCC arranged for current members to offer guided tours of the facility. I was fortunate to be assigned to the club’s unofficial historian and Director of Business Development, Joe Pavia. As a historian myself, I was expecting a somewhat dry account that detailed developments in the sport and the club’s expansion over time, but Joe’s colourful history of the Ottawa Curling Club was anything but. The social historian in me was particularly pleased with the way that he thoughtfully and with a good dose of humour engaged themes of class, gender, and sexuality. In this post, I hope to think a bit more about each of these themes in relation to the OCC and other sporting clubs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This is meant to be a suggestive account, not an exhaustive one. For those of you who are interested in learning more about the club, visit the OCC website or wait for next year’s Doors Open event. Fingers crossed that Joe is your guide!

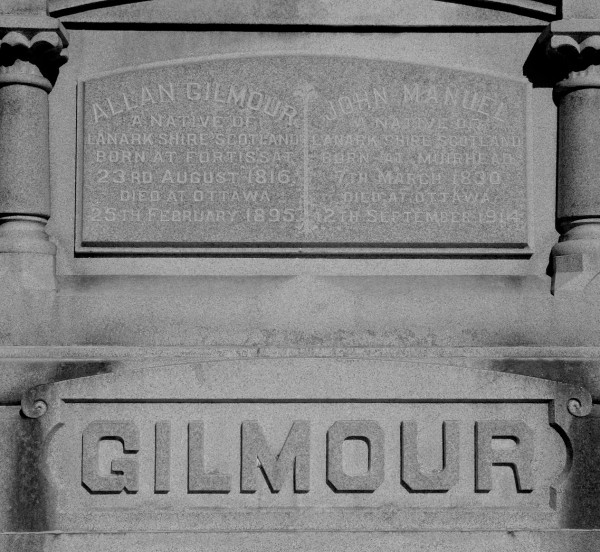

The Ottawa Curling Club, originally the Bytown Curling Club, was founded in 1851 by Colonel Allan Gilmour and his brother-in-law, James Manuel (Centertown’s Gilmour Street is named for the Colonel). Both men were Scottish immigrants who had benefitted greatly from Bytown’s burgeoning lumber industry. The curlers first gathered outdoors for games on the Rideau Canal. By the end of the decade, the OCC had a shed on Lisgar Street to call home. A frame rink with two ice sheets was erected on Albert Street in 1867. Eleven years later, the rink was moved to the now disappeared Vittoria Street (where the Supreme Court sits). The club remained there until the O’Connor Street building was completed in 1916, the same year the Centre Block of Parliament was consumed by fire.

It should come as no surprise that one of the inaugural sporting clubs in Ottawa was dedicated to curling; the oldest sporting club in Canada is the Montreal Curling Club, founded in 1807. Throughout British North America (the precursor to the Dominion of Canada), clubs devoted to the favoured activities of English and Scottish colonists, including curling, cricket, and football (soccer) were commonplace. According to historian Gillian Poulter, these clubs tended to be peopled by the colonial aristocracy, whose interests and allegiances were oriented toward Britain. This, in contrast with the middle class, which gravitated towards “Indigenous sports” such as snowshoeing, lacrosse, and canoeing. Curling had an obvious appeal to British immigrants for its association with the Old World. In addition, as a game originating on the icy waterways of Northern Europe (there is still debate as to whether the Scots or the Dutch invented the game), it seemed well suited to the Canadian climate and landscape. It didn’t hurt that curling was perceived as promoting good behaviour amongst participants. The manner in which the game was played was more important than the outcome.

Curling at this time was a sport of the elite—Joe aptly described it as the golf of the nineteenth century—and the Ottawa Curling Club was no exception. In the early years, OCC members were a who’s who of Ottawa society. In the 1870s, Sir Sanford Fleming, of CPR fame, and Canada’s second Prime Minister, Alexander McKenzie, were both members. Beginning in 1875, the club’s official patron was the Governor General. I should note here that Fleming was only briefly a member. In 1881, he and other curlers left to form their own club, the Rideau Curling Club. The impetus for their departure? The OCC’s policy on drink. Apparently, Fleming and his cronies wished to enjoy a little whiskey with their rocks.

Sporting clubs were more than places to gather for an evening of curling. They were also spaces for socializing. Clubs routinely held “at homes,” smokers, dinners, and the like that cultivated relationships between club members. Access to the club building and participation in club activities was typically reserved for members. To join, an individual usually had to complete a form that included details about their professional, political, and social affiliations. It was not uncommon for sporting clubs to require that a current member vouch for new applicants or for applicants’ names to be published so that members could voice their (dis)approval. Elite clubs, in particular, fostered and buttressed the networks of power that shaped life in the city of Ottawa and beyond.

In addition to reinforcing class privileges, sporting clubs played an important role in shaping gender relations. As with other nineteenth-century sporting clubs, women were barred from membership at the OCC. This decision was likely inspired by ideas about women’s athletic abilities, as well as anxieties about the feminization of society and culture in this period. Women were finally allowed to curl in their own division at the OCC in 1933. The club did not elect a woman president though until 1990.

There is another story worth telling about the Ottawa Curling Club that relates to sexuality. You will remember that the club was founded by Allan Gilmour and his brother-in-law, James Manuel. James had a brother named John, who took over leadership of the OCC in 1895 and remained at the helm until his death in 1914. (Portraits of all three men hang in the entryway to the club.) John and Allan lived together in Gilmour’s palatial residence on Vittoria Drive from 1854 until Gilmour passed away in 1895. John inherited Gilmour’s sizeable fortune. The two men are buried beside one another at Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery. While we can never know the nature of their relationship, the evidence suggests that they were close companions and perhaps even more. As Joe thoughtfully put it, the two men may have shared “the love that dare not speak its name.” Certainly Gilmour’s wealth and social import would have given him greater latitude in his private life than that afforded his social inferiors.

Ottawa is filled with spaces devoted to leisure. Like the Ottawa Curling Club, many have colourful histories that are ripe for the telling. I hope you’ll join me on October 18 to explore the social history and politics of play in Ottawa as we wander through the streets of Sandy Hill and Lowertown. Once again, more information and tickets can be found at the Ottawa (de)tours website.

For those interested in curling history in Ottawa, there is an interesting and well-researched article on the Rideau Curling Club. For another perspective on curling and community, visit Active History.

***

Story and images: Jessica Dunkin is a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Kinesiology and Health Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston. She received her PhD in History from Carleton University in 2012. You can find Jessica on Twitter at @dunkin_jess.