The city is a house built by many hands.

This alone does not make Ottawa unique, but as a place, Ottawa is the most unique city in all of Canada.

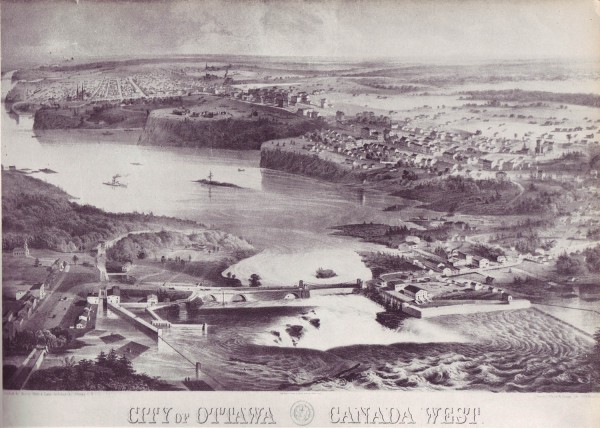

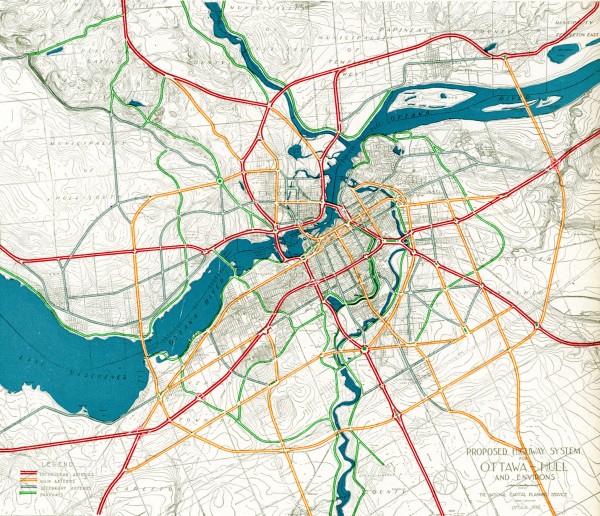

In Ottawa’s history, there was a period of time following the Second World War, when great minds, Jacques Gréber foremost among them, envisioned a National Capital reflective of Canada’s new and unquestionable position on the world’s stage. The great minds of the Federal District Commission tackled difficult problems facing Ottawa and established urban and national requirements. They found a city that had been settled amongst an ideal setting of untouched beauty, but they believed that as a Capital it would be problematic to grow and become the national centre of intellectual development. It was believed that a new city plan would bring about a good civic life and secure prosperity. This new plan for the Capital would bring about material improvements, moral progress, and consequently social order, it was believed.

Today, it is safe to say that no other contribution has played a greater role in defining the urbanscape of present day Ottawa. However, contemporary Ottawa is still locked in a struggle between city and Capital. This duality has come to define Ottawa and makes it the most unique city in Canada. No other factor has played a larger role in defining the evolution of Ottawa’s built form. The urban artifacts of our city have become part of Canada’s collective memory and symbols of our national identity. The Parliament Buildings, the National War Memorial, and the National Art Gallery, are recognizable to most Canadian, regardless of whether or not they have visited our National Capital.

This is a condition of Ottawa that every citizen should be proud of. Since the implementation of the Gréber Plan, Ottawa has been recognized across the country as a beautiful city of cultural landscapes and urban artifacts of national importance. Today’s National Capital Commission, the direct descendent of the Federal District Commission, is owed a great deal of credit for forming these symbols of the contemporary city. However, the work of the National Capital Commission continues, as the struggle between city and Capital will always play a role in the city.

The duality of Ottawa, as city and Capital, is a condition specific to its place in Canada. For visitors and tourists, the National Capital strives to meet their expectations for a place that symbolizes the entire country and is recognized as an object of pride. For local residents daily life in the City of Ottawa is complex and diverse. This side of Ottawa would be difficult to capture in the Official Plans of either the City of Ottawa or the National Capital Commission. Many of the contemporary spatial clashes in the City of Ottawa today are defined by the struggle between the federal National Capital Commission, and the municipal City of Ottawa. In these well intentioned conflicts, it is easy to lose sight of the role of the citizen, the local urban actor.

The successful planning of Ottawa as a Capital occurs on a scale of time that operates outside the lifespan of a building. This is a scale that is difficult for an individual to relate and contribute to. But on a daily occurrence the local urban actor populates the public spaces between the buildings. We negotiate and navigate parts of the city that belong to different time periods and planning strategies. These local conditions are the most relatable aspect of the architecture of the city to the individual. As local actors and citizens of both the City of Ottawa, and the National Capital, it must be remembered that space, and its subsequent planning, has the power to embrace or exclude.

Ottawa’s architectural history extends far beyond the construction of the Rideau Canal or the founding of Bytown. It existed before the explorations of Étienne Brûlé and Samuel de Champlain. Long before European contact, the Algonquin people knew this place as ‘adawe’, meaning “to trade”. It is from ‘adawe’ that we have the name Ottawa. We define trade to be the act of exchanging goods or services for other goods or services. To trade is an important part of society and life. It is a process which requires two parties to undertake trust in the face of risk. This exchange of trust continues to define the contemporary city of Ottawa. Trust plays a paramount role in the compromises and collaborations between the National Capital Commission and the City of Ottawa, trust allows for public consultation on city and Capital planning issues, and without trust there would be no local actors to populate Ottawa’s public spaces. Ottawa as a city is defined by exchanges between parties. Without exchange and trust, there is no city.

I personally invite you to join us for the 27th edition of Ottawa Architecture Week (OAW). This year’s theme is “the capital & the city” and we are looking forward to hearing your ideas and opinions, as we explore the tensions between Ottawa the city and Ottawa the National Capital. This year’s program features a variety of public events that include talks, exhibitions, installations, workshops, film screenings, tours, and panel discussions.

For more information and the schedule of events, please visit: Ottawa Architecture Week

***

Story: Simeon F.A. Rivier is a volunteer of Ottawa Architecture Week. He recently graduated from the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture and is working in Ottawa as an Intern Architect. His professional M.Arch thesis ‘The Post-Industrial Seaway Landscape’ championed a new urbanism focused on community-based spatial agency. His favourite Ottawa pastimes are walking in forests and swimming in lakes.

Images:

- Ottawa Architecture Week Logo

- “City of Ottawa circa 1860”

- “Proposed Greber Plan Highway System, 1950”