The City of Ottawa is carrying out a multi-year project, surveying and evaluating every built structure in the city to determine which resources contribute to the city’s cultural heritage. I worked in the Heritage Services Section of the City in the summer of 2016 and at some point was given the task of photographing every building in Centretown, one of Ottawa’s oldest neighbourhoods. The photographs published here are part of that documentation, the entirety of which will be available to the public in a few years time as an online, map-based inventory. The opinions presented are my own.

Bounded by the Rideau Canal on the east, the Ottawa River on the north, Bronson Street on the west and the Queensway on the south, Centretown’s boundaries define a section of the city which is architecturally and functionally diverse, featuring several sub-areas with distinct character.

South of Gloucester Street, Centretown is primarily characterized by an underlying low-rise residential base dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

North of Gloucester, Centretown is characterized by office and apartment buildings. Most of these buildings are high-rise towers built since the 1960s.

The distinction between these two areas isn’t neatly drawn as many residential towers have been constructed south of Gloucester and fragments of early low-rise residential streets remain north of Gloucester.

Parliament Hill occupies the northern corner of the neighbourhood. Centretown, like much of Ottawa, serves the dual functions of being part of a city and part of a nation’s capital.

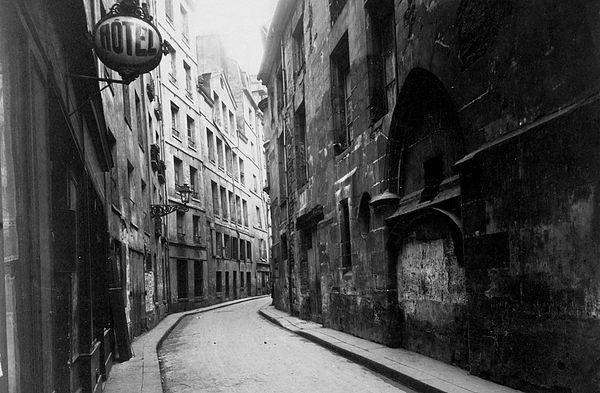

When I set out to photograph Centretown, I thought of Eugene Atget, a photographer who at the end of the 19th century began to document Old Paris, a project he would pursue for 30 years. The late 19th century had seen many Parisian neighbourhoods vanish, redeveloped into the city we know today with its grand boulevards. Massive modernization projects continued into the 20th century with the last of the boulevards built, and the Paris Metro constructed. Atget, along with other photographers, documented the city as it disappeared.

What change will these photographs of Centretown stand in comparison to?

Businesses will come and go. Signage can be one of the most ephemeral but also notable elements of the built environment. Boushey’s Fruit Market, open since 1890, closed July 30, 2016.

Buildings will be constructed, adapted, and demolished. These images capture a moment in time when Ottawa is preparing for 2017, the 150th anniversary of Canada’s confederation, with transformative projects like the redevelopment of the National Arts Centre.

According to the Centretown Community Design Plan, by 2031, 265,000 more residents are anticipated to live in Centretown, along with 145,000 new homes. Residential intensification will take different forms in different areas of the neighbourhood, guided by the Official Plan and other documents.

The indiscriminate eye of a camera pursuing a subject as thorough as “every built structure in Centretown” captures subjects which would otherwise likely not stand out to be memorialized. The commonplace stand on equal footing with the exceptional.

In On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag pointed out how photography is closely related to architecture, and to ruins in particular. She noted how the wear and tear, the stains, cracks and fading of physical photographs over time only add to their appeal, as “many buildings, and not only the Parthenon, probably look better as ruins.” What will the ruins of tomorrow be?

Eugène Atget worked in the early 20th century with the tools and materials of a 19th century photographer. Despite the then recent development and mass availability of the hand-held Brownie camera, he continued to use a heavy large-format camera and tripod, viewing Paris upside-down beneath a blanket. He made prints by laying glass negatives on sheets of silver albumen paper and exposing them to sunlight. Atget’s work, documenting the old houses, shops and streets of Paris, his concern for the past, reveal an anxiety about the often destructive progress of modernity.

When looking at old photographs of cities, we can feel a sense of loss for the buildings, streets and neighbourhoods which were demolished or transformed beyond recognition, but we can also see great improvements to the urban environment. If these photographs of Centretown withstand the passage of time, they will inevitably stand in comparison to all that comes to be in the neighbourhood.

—

Story by Adrian Phillips

Photo source: Heritage Inventory Project, City of Ottawa

3 comments

It is very disappointing to see that important task of photographing Ottawa architecture was performed so poorly….every single image presented here is badly executed. It is even more annoying when you think that public money were spend on that! If you look at many older images from archives you can clearly see that photographers who were given task of documenting the city in the past (late XIX and early XX century) had a good technical understanding of the medium of photography and often also an artistic vision. I would suggest that next time a well experienced architectural photographer would do the job as those images are appealing!

What gov’t would pay a professional architectural photographer a professional salary to do such a thing this day and age? The photos served a technical purpose outside of memorializing a neighbourhood. It’s not a gallery exhibit. The author is simply pondering as an aside what the artifacts of the task he was given will mean in the future

Tough but fair.