As Ottawa takes decisive steps toward giving itself a downtown subway, it is fascinating to find that this is actually the fourth time that plans for grade-separated downtown transit have been proposed. This is typical of growing cities that have had to tackle such a major investment in transit. Montreal, for instance, first proposed a subway in 1910. It would be over half a century before the métro finally opened, in 1964. Likewise, Toronto’s first subway plan dates back to 1909. It took until 1954 to see the first trains roll. Even cities like Paris first discussed subways as early as 1854, and had to wait several decades until the first line was put in service in 1900.

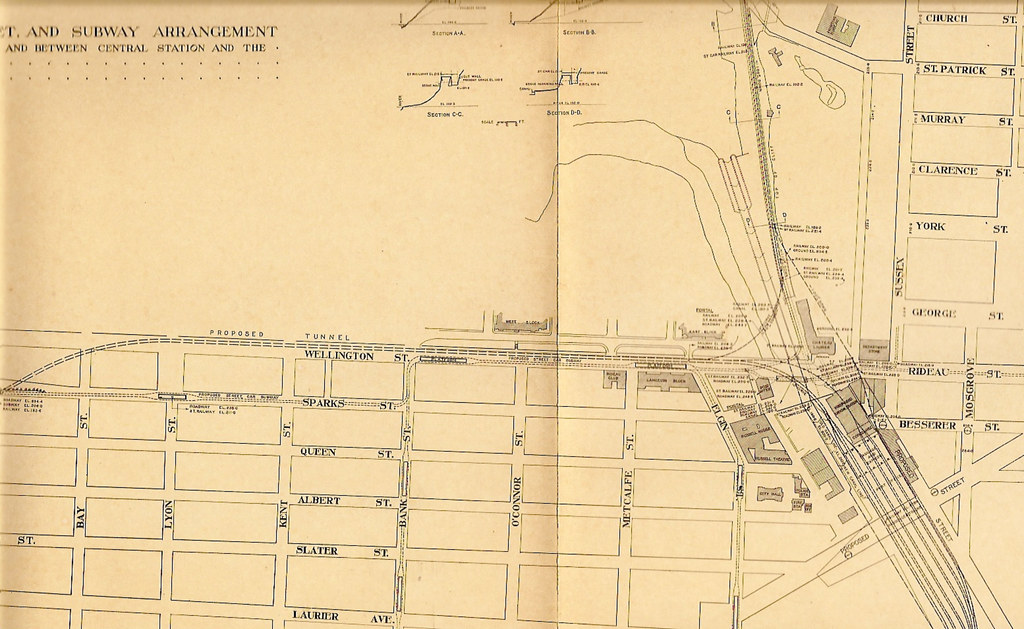

In Ottawa, the first subway plan dates back to 1915. In a report to Parliament, the Holt Commission noted the severe congestion of Sparks Street and arteries leading up to it, including Bank and Elgin Streets. As the drawing below illustrates, it recommended placing streetcars in a subway between Bronson and Rideau Streets, with southbound lines on Bank and Elgin. The portals would’ve been at the escarpment on the western edge, the Rideau Street intersection with Sussex at the eastern edge, and at about Laurier Avenue for the southern edges of the Bank and Elgin lines.

The Holt Report wrote:

“The policy of adopting subway construction is for the purpose of freeing the streets in the downtown centre entirely of street-car business. It is proposed that the transportation lines be brought to the perimeter of the central section of the city above ground, and there enter subways which shall extend across the heart of the city. This principle is being adopted universally to relieve congestion on narrow downtown streets.”

Holt’s subway was by no means the mass rapid transit systems of larger cities or anything resembling today’s LRT subway plan. Streetcar subways were proposed in response to growing vehicular chaos on central city streets as a way to segregate regular streetcars from surface street operation. Boston’s subway started out as a streetcar subway in 1897; today it is part of the MBTA’s Green Line. Before it was incorporated into a longer network of subways, Boston’s streetcars operated in the downtown via the subway and then provided on-street service with regular stops. This lasted well into the 1950’s.

The Holt plan was never implemented. With Canada at war and the destruction of Parliament by fire in 1916, the government was distracted away from following up on the report’s recommendations. Only a few of its elements were picked up in later plans and survive today, notably the strong building edge along Elgin Street, with its uniform cornice lines framing the view of the War Memorial.

It would take another 54 years before underground rapid transit would again be seriously considered in Ottawa. In 1969, ten years after the abandonment of streetcars, the Ottawa area found itself having grown past the half-million population that the 1950 Gréber Plan had forecast for the year 2000. This rapid growth, along with the decentralization of employment and systematic segregation of land uses recommended by Gréber, made car traffic rise by several multiples over the increase in population. Again, congestion became a serious issue and a Washington, DC consultant, Philip Hammer, was commissioned to prepare a plan for the downtown core.

In 1969, Hammer released the Ottawa Central Area Study for the City, the NCC and the Ontario Department of Highways. The Hammer Report was premised on Ottawa reaching a metropolitan population of 1,492,520 by 1996. The report’s main conclusion is that “the existing street system is not adequate to serve the projected future development and that the alternatives worthy of future consideration were the freeway-oriented, transit-oriented and balanced systems”, a trio of alternatives discussed at length in the report.

This being the age of freeway construction, one of the choices advanced by Hammer is an all-freeway solution to Ottawa’s congestion dilemma. The so-called freeway-oriented scenario called for freeways to be extended into downtown from the Queensway by a new King Edward Expressway, which would have required the demolition of all buildings between King Edward Avenue and Nelson Street north to the Macdonald-Cartier Bridge, and a Lemieux Island Expressway, which would use the Prince of Wales bridge to cross into what is now Gatineau. This scenario would, among other things, require the creation of 40,000 new parking spaces downtown by 1990.

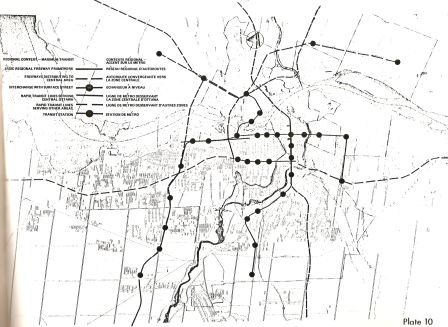

The transit-oriented scenario called for the construction of a subway between Lebreton Flats and Sandy Hill, under Queen and Besserer Streets, extending eastward into Vanier and westward to Nepean as a surface rail line. The “maximum transit” scenario would’ve seen rail service reach St. Laurent Shopping Centre in the east and Barrhaven in the southwest, while the “balanced system” had rail service stop at Montreal Road and St. Laurent in the east, and Merivale and Meadowlands in the southwest.

Among Hammer’s other proposals, he envisioned a continuous urban fabric linking the downtowns of Ottawa and Hull over the Portage Bridge, “to promote developments that will link the North Shore in Quebec to the Central Area in Ontario, symbolizing the integration of the two dominant cultures of Canada.”

Some of the other recommendations found in the Hammer Report were implemented shortly after. Downtown building height restrictions had been capped at 150 feet until the 1960’s; Hammer proposed maximum-density zoning through Floor Space Index and angular planes to allow for taller highrise buildings downtown while protecting the views to, and predominance of, the Parliament Buildings on the skyline. He also proposed using zoning to restrict the extension of commercial office development south into Centretown. Notably, he advocated for Rideau Street to retain a central role in regional retailing by establishing a major indoor mall. With interesting foresight, he saw Richmond Road in Westboro becoming a major retail corridor in the 1990’s. And he also called for a Ceremonial Route to link major federal buildings and landmarks, as well as a Convention Centre replacing the old Union Station building at Rideau and Sussex, steps away from the facility that is currently under reconstruction.

Hammer’s subway was never built, but neither were his freeways. In fact, his Plan gave rise to Ottawa’s own freeway revolts, leading to the creation of community associations such as Action Sandy Hill, which formed to (successfully) defeat the King Edward Expressway. As for rapid transit, the decisive nail in the subway’s coffin was an updated population projection issued by the National Capital Commission a couple of years later in which the area’s growth was revised downward significantly. With the onset of a recession in the early 1970’s, large public expenditures were put on the back burner and Hammer’s subway quickly evaporated from Ottawa’s to-do list.

However, the need for rapid transit did not go away. In fact, the new Ottawa-Carleton Regional government (formed in 1969) was quickly seized with the problem and, in 1976, released the Rapid Transit Appraisal Study. This study analyzed a variety of options including a metro and an LRT system, concluding that for its size at the time, Ottawa wasn’t yet ready for rail rapid transit – but would be within two or three decades. The Transitway was born from that report. It was a made-in-Ottawa solution, different from the route taken by Calgary (surface LRT) and Edmonton (LRT with downtown subway) in that it called for the creation of grade-separated, high-capacity bus corridors designed for conversion to rail, starting with the outer edges of the system with the anticipation of downtown grade-separation at later stages. Basically, the Transitway solution was designed to “groom” the city for rail rapid transit by building ridership along with population growth until such time as rail became justified to meet transportation needs.

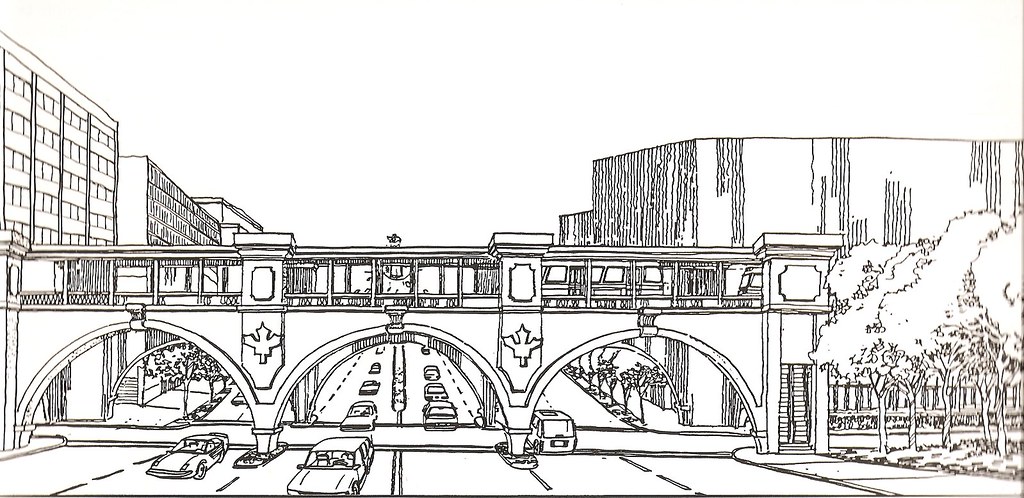

That “later stage” came in the late 1980’s in the form of a proposal to grade-separate the Transitway through downtown with a bus tunnel. At the time, the Regional government presented a study in which two main options were considered: one was to elevate the Transitway above Albert and Slater streets; the other was for a twin bus tunnels under both those streets.

The elevated option was rejected for a variety of reasons, none least because of its profoundly disruptive effect on the north-south vistas to the Parliamentary precinct and several other national monuments and landmarks, as the illustration below shows (a view on Elgin Street looking north to the War Memorial):

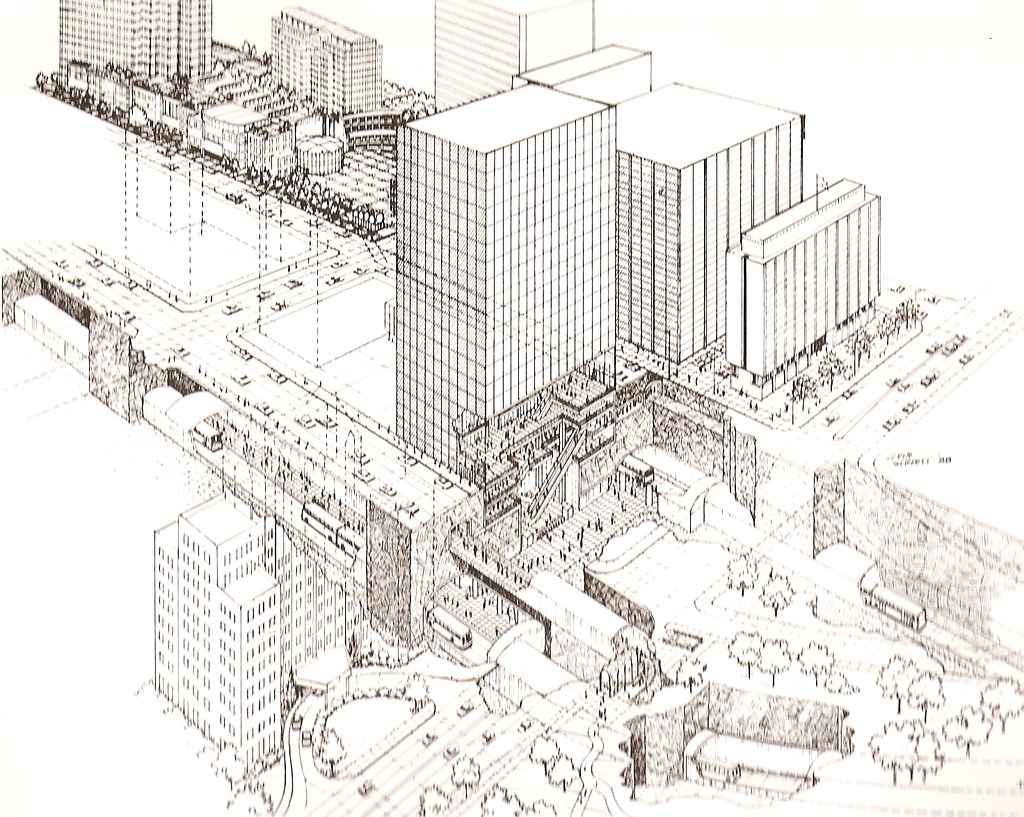

The twin-tunnel was carried forward as the recommended way to go. It would have featured four underground bus stations (Bay, Bank, Metcalfe and Rideau), with the alignment then following the existing Transitway south toward Campus station in an open cut that gently rose above ground.

Two things killed this project, both political. At the time, as is the case today, the debate over the future of rapid transit was emotionally charged and funding was a major issue. Then-Ottawa Mayor Jim Durrell, during a media scrum, made the tactical mistake of letting his guard down, impatiently remarking that “costs were irrelevant”. Durrell, for all his visionary leadership, did not properly read the public concern about the money that this project was going to cost. His main argument that the tunnel was a city-building initiative and that it was being designed for conversion to rail, was instantly lost with that comment. The media had a field day with his statement.

The other undoing of the Transitway tunnel was a statistical tidbit which claimed that the tunnel would save commuters an average of about four minutes in their crossing of downtown. This was grossly taken out of context by media columnists eager to exploit the burning controversy over the project. The time savings may have been an “average” of four minutes, but during peak times buses were already experiencing severe delays going through the core. Regardless, for the media, hundreds of millions of dollars for four minutes became a mantra. For better or for worse, the bus tunnel project was slowly and painfully put to death.

CONCLUSION

Any large and growing city that embarks on a rapid transit project of any magnitude will experience controversy. Ottawa is not new to this, as were all other major cities that have built subways or rapid rail transit lines. The stakes are high: the scale of the investment involved in such a project, the structuring power of rail transit, and the implications for real estate, retail and scores of other interests including which communities will get the line and which will get it first, all translate into debates that by necessity are divisive, often bitter and extreme, and all too often play to the common lowest denominator (costs, taxes, “impacts”, etc.).

In our current LRT debate, it’s worth remembering that the original Chiarelli plan called for a north-south line to serve the new community of Riverside South, thereby theoretically avoiding the need for massive roadbuilding to link that new suburb to the rest of the city. The main reason that project got killed was that larger, more established suburbs were not first in line for the transit upgrade. The current plan correctly starts with downtown as the main element of the plan and its first phase, but also starts out by serving the heavily-populated east and west ends, in that order. There still is a north-south line, but it only gets built in later phases.

Still, one only has to look at any city that has matured enough to take the step forward and build a system to see the evidence of how a city can be transformed. One would not dream of Toronto without its subway. We also quickly forget that Toronto wasn’t much larger than Ottawa at the time it started building its first line. One also has to look at European cities that are sometimes smaller than Ottawa is today (Lille, Bilbao) and have built a metro or extensive LRT systems, to understand how rail rapid transit really is the only way to structure growth.

Fourth time lucky for Ottawa? The current iteration of an underground system through downtown has not been without its share of birthing pains. In fact, we are still at the onset of labour, undergoing severe contractions. But the baby must be allowed to come into the world.

There remains in the media today a vocal faction arguing that LRT service can function at-grade. Cost, again, is the main reason invoked in trying to kill the tunnel. As the City proceeds through the debate, it remains vitally important to demonstrate that a surface LRT system can only accomplish so much. One look at downtown today during peak hour should be enough to show most reasonable people that, be it buses or trains, the amount of people moving through the core is such that any surface operation dooms the system to delays and unreliability, both fatal to establishing transit as the quicker and more convenient option. If we pay for a surface LRT system for downtown, how long will it be before we are faced with the same congestion dilemma? Ten years, tops? Why, in other words, would a city spend so much money on a stop-gap solution when it can give itself infrastructure that will last centuries and fix, once and for all, the problem of slow transit through the core?

There are also bizarre arguments to the effect that the tunnel’s hidden agenda is to help cars move quicker through downtown and therefore, this is really a car-centric plan. Again, the argument must be vigorously defeated with sound reasoning. A surface operation means that people have to wait outside. A subway means weather-protected stations. A surface operation curtails the potential of a high frequency service. A subway offers the potential for two-minute trains. And this is really the key factor in expressing the significant upgrade in service that the LRT subway will give Ottawans. In other words, the current subway plan is a commuter-oriented plan. It will make transit faster and friendlier, a pleasure to use – not a dutiful token investment that really changes nothing and leaves the car as the fastest, more comfortable way to move around.

Right now, people have to wait outside for their bus (which may be a 95, or may also be one of the dozens of express routes that mingle with the 90’s series lines). There are also rural routes and out-of-town transit companies that mingle with the 35’s, 62’s and 77’s of the world that take commuters from downtown to dozens of specific suburban communities through the Transitway. Miss your bus and you’re waiting –outside– even longer.

With an LRT subway, every train is your train. People will take the train to a station that then becomes the main transfer point, so the distribution of crowds takes place outside downtown. With a high-frequency service, people’s schedule will revolve not around the downtown departure time (which is rendered meaningless by congestion), but around the departure times at the transfer station. Those times will have a much greater chance of being exact, since buses leaving transfer stations won’t be stuck in downtown traffic.

Ottawa is about to embark on the most exhilarating transit project this generation will know. It is a rare privilege to live here in these times and to see the city reinvent itself in such a forward-looking way. The only thing our children will ask us is, “what took you so long to do this?”

Photo by Oran Viriyincy

22 comments

What a useful and informative post. Thanks for the history – it really helps put the current plan in perspective

Thanks for this. I’m definitely a supporter of the DOTT, but I do wonder about this passage: “With an LRT subway, every train is your train. People will take the train to a station that then becomes the main transfer point, so the distribution of crowds takes place outside downtown. With a high-frequency service, people’s schedule will revolve not around the downtown departure time (which is rendered meaningless by congestion), but around the departure times at the transfer station. Those times will have a much greater chance of being exact, since buses leaving transfer stations won’t be stuck in downtown traffic.”

It seems to me that anyone against the DOTT could easily come back with something about how if you just get the local buses out of the core and have them depart instead from Tunney’s Pasture, Hurdman, Blair, Baseline or wherever, you’re clearing a lot of congestion out of the core just like that. Let me rewrite your paragraph: “With only 90 series buses traveling through the core, every bus is your bus. People will take the 90 series to a station that then becomes the main transfer point, so the distribution of crowds takes place outside downtown. With a high-frequency service, people’s schedule will revolve not around the downtown departure time (which is rendered meaningless by congestion), but around the departure times at the transfer station. Those times will have a much greater chance of being exact, since buses leaving transfer stations won’t be stuck in downtown traffic.”

Again – I’m for the DOTT, but I wonder what you say to that argument. (Also, when I’m drafting comments on your site, the ‘Enter’ key on my keyboard appears to produce a tab instead of jumping my cursor to a new line. If my formatting is messed, that’s why.)

Josh, I see where you’re going, and that could then lead us back to a bus tunnel if we want to also ensure high capacity with an all-bus system. What I see, though, is that the switch to LRT is also about moving more people through the core, and the tunnel is about doing it fast and without interference from cross streets. Both are part and parcel of the transit upgrade we’re embarking upon. Because, if you rewrite my sentence the way you did, the part about buses being on time at their transfer station is iffy as long as they stay on the surface. And the same would apply to surface trains.

My response is to Josh. If you get rid of the local buses you still have congestion on the streets. Cars still have to turn left or right and accidentally block the bus only lanes in the core. I’m against any at-grade “solution” because it doesn’t actually solve anything. We NEED a tunnel. I don’t care what goes through that tunnel, be it Buses, an LRT, HRT, Tram or Trolley…but Ottawa needs a downtown tunnel. I don’t take the bus anymore because it’s so unreliable going through the core. If there was a tunnel, I know that my bus/train/tram/trolley would get through the core quickly and on time.

Very fascinating post, thank-you! I’m with you in hoping that this baby is born healthy!

Do you have a quick summary of why Ottawa got rid of its streetcars in the first place?

Thanks.

chris.

I actually have seen most of this info before but it has never been packaged so nicely. One thing about the bus tunnel of the late 80’s and early 90’s though. The main reason for killing it was not local, but provincial. At roughly the same time, the TTC in Toronto had it’s Let’s Move plan of subway extensions cut back and eventually killed as well. The main culprits were the NDP government in Queen`s Park inexperience and the recession of the early 90`s. The NDP had made many promises during the election capagin of 1990, one was that they would greatly increase capital as well as operational funding for transit in Ontario. Much time was lost early on because of the complete lack of expierence in managing large construction projects. Time was lost teaching NDP MP`s how you officially plan to build things and tender them for construction. (This is common in new left wing governments as is teaching new right wing governments how to manage departments that don`t operate on profit as their main motivation for service) A generalization yes but, it is often true. Our own current mayor had to be taught how local government worked as he had never spent much time in city hall before he was elected and he admitted to that publicly. Up to a year and a half was lost by the time the province was really ready to begin acting on it`s promises. Then the recession of the early 90`s was in full swing and revenue was way down, as a response to a big provincial budget overun, the bus tunnel as well as several subway lines were shelved. The approved money (75% of capital funding for transit was provided by the province at that time) was cancelled and focused on other things. Only one TTC subway line out of 5 planned was ever built and that almost didn`t happen as well.

One other thing, As a transportation planner there is one big reason why the the DOTT is so badly needed. What is often overlooked by people in the debate over switching our BRT system to a LRT system with a tunnel is operating cost. Our bus system is slowly being killed by it`s operating costs. The capital costs for a LRT tunnel can be bad but, that it is a one time cost. Once the tunnel is paid off (barring construction problems) your done paying out cash. Busses in our downtown have been operating well beyond the effective capacity of Albert and Slater for so long each extra bus we add increases our operating cost faster than a bus full of passengers can lower them. The reason is ,industry wide, between 68-79% of transit operating costs are people, regardless of it being trains or busses. We push between 360-400 busses(180-200 per direction) through downtown per peak hour. We move 10500-11000 passengers per peak hour per direction. To compare Cagary moves between 9500-10000 people per peak hour per direction however, they only have 21, 3-car trains operating on there entire system. Calgary can not move any more because of platform limitations and is now in a process of lengthening the platforms for 4 and 5 car trains. They will still have the same number of LRT trains operating, 21 (the extra LRT cars are already on sight and paid for) and their corresponding drivers but they will have increased their operational capacity between 33-60% depending on the car design. Thus increasing their per operator income without greatly increasing operating costs.

Thanks for the feedback. Like I said, I wasn’t making the case against a tunnel – I’m firmly in the pro-tunnel camp. It’s just an argument that I’ve heard/read from some bus/status quo supporters. And it’s not wholly without merit: there’s a lot of deadwood floating along Albert and Slater during any given afternoon rush hour, in the form of local buses near the start of their routes that are about 1/10 full.

Going forward, we absolutely need a tunnel with rail running through it, but as a short-term fix, I can see the value in exclusively (or nearly-exclusively) running 90-series buses through the core, with local routes starting at Transitway stations further afield.

Alain,

A nice historical overview. I never knew about the 1960s-era subway plans, though I knew about the earlier Holt and later bus tunnel plan.

Unfortunately you’ve fallen into the same “surface LRT is a short term solution” trap that many others do. Would it surprise you to learn that the City’s own projections claim that surface LRT would be sufficient for the 2031 planning horizon? It’s not a 10-year solution but a much longer lived one. Surface LRT was rejected not on capacity grounds as commonly believed but on urban design grounds, of all things. It’s the position of your transportation engineering colleagues that surface LRT is an urban design nightmare. I suggest you read the section of the 2008 TMP background report in which surface LRT is rejected – you may be surprised at how appallingly written it is.

To indulge a moment in “what could have been” historical revisionism, if we had not made the mistake of building the Transitway as a busway 25 years ago but had followed Calgary with its surface LRT system, we would today have a downtown surface LRT system with decades of capacity still left in it and we’d be debating which direction to extend LRT rather than contemplating conversion of a relatively short length of transitway that is not-so-easily converted.

None of which is to say we shouldn’t be planning for a rail tunnel; we should. The difference is that we can build it over a longer period, taking advantage of opportunities as they present themselves to build a segment or station here and there. But again, this sort of thing seems to be eschewed in Ottawa, where an opportunity to build a station in the basement of the new central library will be passed up in favour of mining one out from within the confines of a tunnel underneath Albert Street just metres away. The stations will also be far deeper than necessary and far too few in number (the bus tunnel plan of the 1980s called for four – not three) – a mistake that will be very hard to fix and will dwarf the mistake of the Transitway in its significance over the decades to come. This is what happens when transportation engineers are allowed to “plan” transportation infrastructure. Just as Clémenceau said of war and generals, transportation is too important to city life to be left to the transportation engineers.

Shame that you guys are still waiting on grade separation through the downtown, and probably won’t see it in your lifetimes now. Ottawa already has one of the best BRT systems in the world, and the coverage and stop spacing outside the core is far more ideal than we have in Toronto. Even if a tunnel was built now, it would do wonders for the efficiency of the system and could be upgraded to LRT (or even both BRT and LRT like in the Seattle pic) afterwards.

In response to David James’ comment, I don’t have an opinion on whether or not the tunnel is too deep. The arguments seem technical, and are somewhat dependent on choice of route, which has so many variables that I’d rather not try to figure out how they were all weighted.

But I do have an opinion on the comment that the tunnel is too deep AND has too few stations. To my mind, one of the benefits of deep stations is they allow a larger spread of entrances. The proposed entrances in the current plan provide coverage every block or so. I don’t see how putting the entrances closer together and adding another station would improve the situation appreciably.

Like David, I also wish the city had followed Calgary’s path. I’m not convinced that surface rail would have as much capacity has he thinks, but there is no doubt that we would be basing the tunnel decision on an experienced assessment of data instead of projections and conjecture.

Excellent research and history Alain. However I would not be so convinced of the advantages of Surface LRT (sLRT) over LRT in the tunnel (DOTT-LRT). The four proposed downtown stations will be equivalent to 10 storeys underground, deeper than our deepest parking garages. While a few cities (Moscow) have subways that deep or some cities (Washington) have a small number of very deep stations, most subways stations are shallow: one or two flights of stairs or escalators.

In Ottawa you will need to take 3 to 5 minutes of escalator ride to go 10 stories and most sketches so far show this as 3 or 4 separate escalator rides (not one long one like Moscow or Washington). See clip below.

Plus it will be hugely expensive to excavate these deep stations and run the many long escalators. But as Durrell alluded to, the consultants planning and designing it do not have to pay for it, and they make more money the more it costs. And the Councillors today will not be around a decade from now when the DOTT over-run bills roll in and everyone realizes the DOTT has not helped the downtown commuter save time versus sLRT.

I would rather wait for a few minutes outside for the next LRT train like in Calgary downtown rather than take five minutes to go down to a very deep station (let alone the safety and security risks down so far) and then wait another 5 minutes for a 6 car-long DOTT train to come along. Few tourists are willing to take a subway anywhere, whereas with an LRT line, they can see which way the track and train is going, and where they are. I came out of the downtown Skytrain subway station in Vancouver (yes there are a couple of underground stations downtown) and no idea which way to turn to get to my hotel.

Wikipedia: Rosslyn (Washington Metro): …. the shared rail line into Washington passes through a rock-bored tunnel, Rosslyn station is quite deep—the deepest on the Orange and Blue Lines. Its platform lies some 97 vertical feet below street level (though its ceiling is nearly 60 feet high). It features the third longest continuous escalator in the world, at 437 feet (133 m); an escalator ride between the street level and the mezzanine level takes 159 seconds.[2]

By the way, in the late fall of 2008 and again in early 2009 I had brief conversations with the head of LRT planning in Calgary. Due to the current platform expansion project and the number as well as the capacity of future LRT lines, early planning has started on a tunnel in downtown Calgary. The tunnel is planned to begin operations between 2020 and 2030. The current plan is to put it under 7th or 8th avenues, however they are very early in the planning process and this could change.

Mr. Miguelez,

This is the best presentation I have yet read on the historical aspects of a downtown Ottawa train tunnel. However, you omitted the 1910 CPR proposal filed at the city registry to run tracks on the bed of a drained Rideau Canal and to bore a tunnel 50 feet under the surface of downtown Ottawa and to run steam engine trains under Wellington Street toward the then called Union Station in LeBreton Flats.

I do not share your conclusions, however, because you are overlooking some very real and pertinent problems to this DOTT project. Foremost is the unpredictable cost due to engineering issues while another is an inadequate foresight in the transition needs of the entire region in this second decade of the third millennium. I describe the present DOTT plan as “tunnel vision”.

The 1910 CPR proposal and the fact that Herbert Samuel Holt, a major investor in the Canadian Pacific Railway as well as being the chair of the Royal Bank of Canada, a rich man and a civil engineer, may have led the Conservative Prime Minister, Robert Borden, to appoint Holt as chairman of a Federal Plan Commission to plan the future growth of the city of Ottawa and the city of Hull. Edward H. Bennett, an American architect, was also appointed to this Commission and hence the Holt-Bennett Plan of the “Holt” Commission.

Mr. Miguelez, you neglect to say that two tunnels were envisaged: one under Wellington St. for the steam railroad trains and one somewhat under Sparks St. for electric streetcars that would end up close to the newly built Union Station for a quick transfer to trains going east to Montreal or north to the Hull train station and beyond over the then recently built Alexandra Bridge. This plan, known as the 1915 General Plan for the Cities of Ottawa and Hull of the Holt Commission and tabled in the middle of the First World War, was also proposing a federal district to carry out its proposals. Then, as well as now, such a concept was and still is deemed unacceptable by the governments of Ontario and Quebec.

The cost of a downtown tunnel in Ottawa is presently estimated at 2.1 billion dollars. This is an incredible sum. If each of those dollars would be a kilometre, the sum would be fourteen times the mean distance between the earth and the sun. If each of those dollars were merely an inch it would travel 1.3 times over the circumference of our planet. This is a capital cost of great magnitude to be totally paid with taxpayers’ dollars.

We really have no idea how much this tunnel will cost because we can only make learned guesses at what is underneath our streets and buildings. The mass behind the cliff face upon which the Parliament Buildings are built is primarily limestone with random cross-sections of black shale. Furtively throughout are water-permeable small faults diverging from the Gloucester fault. This fault, starting somewhere between Ottawa and Cornwall and ending somewhere in the Gatineau hills, meets the Eardley fault near the downtowns of Ottawa and Gatineau. It crosses somewhat perpendicularly the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben, a topographic depression and still seismically-active ancient rift valley in the Canadian Shield. The Ottawa River flows through this graben.

Recent events of the seismic activity of the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben are the 1935 Temiscamingue earthquake (6.1 on the Richter scale) and the Lake Kipawa earthquake east of North Bay in 2000 (Richter 5.1). A 4.5 Richter earthquake happened in Thurso on February 24, 2006. In comparison, the Haiti earthquake measured 7.0 on the Richter scale.

The Ottawa-Gatineau area, being the 4th largest metropolitan area in Canada, is also listed by the Geological Survey of Canada as the third in Canada as an urban area most at risk of an earthquake. This first at risk is Vancouver on the Pacific Rim and the second is Montreal which shares the same seismic zone as Ottawa.

Montreal had a Richter 6.2 earthquake in 1732. The Geological Survey of Canada estimates that there is a 10% chance of an earthquake in the next 50 years that would be strong enough to damage buildings in Ottawa. Of course, being built upon solid rock, there would conceivably be less damage to the Ottawa-Gatineau downtown buildings than to houses built on soft soil and Leda clay in the areas south of Orléans. However, structural damage with water and air intrusions would probably happen in the underground of Ottawa.

In 1961, an addition the Bell Telephone building at the corner of O’Connor and Slater was built on Slater Street. After completion, the basement floor started to heave and this necessitated the continual re-alignment of the generators and switching units plus freeing the partition walls from the ceiling. Over a period of time, this heave reached 10 cm (4 inches) over a floor area of 223 square meters. Although the building was more than 2 kilometres away from the Gloucester fault, it was believed that the damage was due to the numerous minor faults emanating from the Gloucester fault. An investigation was done by scientists from the National Research Council.

This investigation came to the conclusion that building across a fault zone permitted the entry of air that reacted with the water and sulphides present in the fault’s cracks that created an acidic medium that activated dormant bacteria to oxidize inorganic compounds in the shale which converted to substances with a larger mass and so on ….

Let us keep in mind that this proposed downtown Ottawa tunnel transit system is much more than just a tunnel. It involves the building from the surface to deep underground of stations, entrance rooms, hallways, escalators, stairs, platforms and various servicing areas. All of these will have to be built by detonating through limestone and shale. Any structural and geological problems would necessitate cementation at great cost.

I do not believe that burrowing a multi-billion dollar black hole under the vaults of the Bank of Canada is such a great idea. We can do better. YES WE CAN!

(to be continued)

Jean-Claude Dubé

Ottawa, Ont

“A surface operation means that people have to wait outside. A subway means weather-protected stations. A surface operation curtails the potential of a high frequency service. A subway offers the potential for two-minute trains.”

Since this is a northern country and it snows quite a bit here, I have to wonder, wouldn’t surface operations increase operating costs as (opposed to capital costs)? Isn’t it then sort of a shift of the cost towards the future?

In Montréal they are making similar noise about expanding the métro on the surface. I doubt the wisdom of that idea too.

Hello,

Re my DOTT posting Feb.1, 2010:

The footnotes that I had in a Word document did not carry over in the posting.

For those who are interested, they are:

1. for the 1910 proposed CPR tunnel

The Ottawa Citizen, May 5, 1910, p 1

2. for background on the Holt Commission

Barry Podolsky, The Ottawa Citizen, Jan 23, 2009

3. for geology of the Ottawa area

Wilson A.E., Canadian Field Naturalist, vol 70, no 1, p 1-68, 1956

4. for floor heaving at O’Connor and Slater

E.Penner, J.E.Gillot, W.J.Eden. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, vol 7, p 333-338, 1970. NRCC 11437

Jean-Claude Dubé

Jean-Claude, you say that the cost of our subway is astronomical. At $2.1 billion, if each dollar were a kilometre, we could go from the Earth to the Sun 14 times. In 2009, with your tax money and mine, the Federal and Provincial governments purchased an equity stake worth $13 billion in GM and Chrysler. If each of those dollars were a kilometre, we could go from the Sun to the Earth 86 times. And we don’t even know if those companies will even be around in 5 or 10 years! Whereas our subway will still be in service in a hundred years. Respectfully, I have to say that every time I read about costs, the question I ask is where are we really putting our priorities. For the federal and provincial governments to truly speak from a position of leadership on environmental and sustainable transportation matters, I would suggest that there is no better way to walk the walk than to be fully involved in the Nation’s Capital subway project.

Alain,

The arguemtn that this is a car-centric plan isn’t actually so bizarre. If you look at the city’s plans and all that the talking heads from the city have put out there, there’s no real discussion of how a tunnel in the downtown could be an impetus for transformation of the downtown, or how it could free up space for better pedestrian facilities or bicycle lanes (the latter being something the city doesn’t even appear to think to be favourable additions to the city). Given the city’s history of auto oriented development Alain, I think that writing off this concern as bizarre is a tad condescending. After all, aren’t we still having a battle over the Alta Vista Expressway in this town?

Secondly, If a tunnel is so much better for providing shelter for riders, why are so many of the shelters outside the core not even fully enclosed?

I think the big issues with the tunnel are that:

1) Whenever you take away surface transit in favour of further apart stations in a tunnel, you can easily create dead spaces on a street. Look at some sections of Yonge Street in Toronto, and you’ll see that the development clusters around stations, not in a linear fashion as surface LRT or streetcars will promote.

2) Unlike other cities, we are not simply putting a busier part of the system below grade in response to demand. We are trying to build out to a very advanced state for opening day, which is why we have a light rail line that doesn’t even cover a long distance. Build the system now, and if we have 10-20 years where surface operations are viable, use them, then go underground.

3) Surface rail would not be a throwaway cost as the city claims, in any event. If we actually build the Carling LRT it could always come downtown at grade, to complement underground services.

4) There’s not enough stations on the tunnel. Bank Street, the most significan north-south commercial corridor in the city doesn’t get a station. WTF??? For that matter, why does Sandy Hill get a station that is farther away than the already desolate Campus Station and lose Laurier? If tunnels are not as constrained by right-of-way as the surface, why not build it at King Edward and Laurier, you know, close to the community, then tunnel under King Edward to Lees. it should more or less be the same distance.

5) Anyone who thinks that a tunnel will be built for $600 million with 4 stations is wilfully delusional. Look at the costs in other cities, and tell me how ours are going to be 50% lower than theirs.

As you can see, there are some pretty good reasons to believe that this tunnel is going to end up not promoting any great shift in urban development and auto oriented patterns in this city. The older neighbourhoods of Ottawa will STILL have crappy access to rapid transit, and there’s no plan to deal with the former bus lanes on Albert and Slater. Sounds like business as usual at the City of Ottawa to me!

With an LRT subway, every train is your train.

= = = And every bus could be your bus, too, or almost everyone, but the comfort of suburban asses is politically paramount in this town. So, even in the face of yet more delays — I give it at least another half-century in this pathetic excuse of an over-governed city — in LRT, we won’t even have BRT, either. Just BT. Sad, sad, sad.

Ottawa already has one of the best BRT systems in the world

= = =

No, it doesn’t. Ottawa has Bus Transit. It’s not especially rapid, and is decidedly NOT rapid at peak.

This first at risk is Vancouver on the Pacific Rim and the second is Montreal which shares the same seismic zone as Ottawa.

= = =

That would be the Vancouver which has a rail-based transit system, including extensive underground RoWs and stations, and the Montreal which has a metro, right?

If the first- and second-most seismically active large cities in Canada can handle underground transit and its risks — to say nothing of the cities in Japan, California, China, and Europe which are even more seismically active — then Ottawa can handle them, too.

What’s next? Dredging up Jim Watson’s terrorists?

Thanks for initiating this conversation, Alain. Sorry I missed it the first time around. Unfortunately, this website doesn’t let you get an e-mail subscription to the comments, so I’m not sure how many of the previous commenters will see my responses to some of their points.

The main problem, though, is a historical perspective on transit tunnel projects does not translate to a historical perspective on City-wide transit projects, so one can’t jump directly to Alain’s conclusion that DOTT is therefore the way to go.

—

Alain wrote: “The current plan correctly starts with downtown as the main element of the plan and its first phase, but also starts out by serving the heavily-populated east and west ends, in that order. There still is a north-south line, but it only gets built in later phases.”

Both points are disputable. The East and West arms don’t go out to the suburbs, as the cancelled 2006 plan did to the South (that plan’s biggest flaw was the downtown component) . They were discounted because not enough people live close enough to where the stations would be (never mind the number of people who actually take transit through those stations). Suburban extensions are not planned until beyond 2031.

Secondly, the extension to the South is not a later phase, but a parallel part of the 2008 TMP that is to be built in a separate project in an independent timeline. Because much of the planning for that line has already been done, the EA and construction can happen in a matter of a couple years, though it wouldn’t make sense to finish it before the DOTT is ready. (Not that I agree with the N-S component, but that’s a separate issue)

—

Re: “Every train is your train” and Josh’s comment about “every 90-series bus is your bus”: While it may not be a perfect or long-term solution, you could certainly relieve some of the pressure on downtown with “bus platoons” or “bus trains”: Between, say, Hurdman and Bayview, Send out articulated buses in sets of three: a 95, a 96, and a 97, with no other buses travelling through the downtown Transitway corridor. You could conceivably alternate these with a set comprising of a 85, 94, and 98. The important thing is that they arrive in order, and they all leave each station at the same time. This way you know (1) where to stand if you want the 96, and (2) if this 96 is full, the next one will arrive in the next light cycle.

As Josh suggests, the reason we don’t do this is that transfers are unpalatable to suburban commuters. Why are transfers unpalatable to suburban commuters?

– For one, they’re spoiled by single-seat “express” routes that toodle around their neighbourhoods and go all the way downtown. They then travel empty all the way back to the suburbs for another round of toodling. Having to transfer to a 90 series bus means that whatever they do to occupy themselves (e.g. reading a book) gets interrupted, and on the second leg they may have to stand the whole time.

– Second, because of the “express” buses that focus on the 24% of commuters who work downtown, the non-“express” buses that don’t go downtown (the ones to which commuters would transfer if they didn’t take the express) don’t have as many riders, and thus don’t come by as often, making a long wait for the transfer.

The important question to ask is, if the switch to a hub-and-spoke model is unacceptable enough that we can’t do it now, why would it be acceptable to commuters if we force it with a train? And with the trunk line moved underground, we have no guarantee that the “express” buses wouldn’t continue downtown. City Staff say that people would be more likely to transfer to a “higher order” level of transit, i.e. from bus to train. But what of the return trip? What of people who have to commute across the City? If anything, a hub-and-spoke model should be more palatable with buses because you can get on anywhere between Kanata and Orléans, not at Blair or Tunney’s.

An important consequence of ditching the “express” buses for a hub-and-spoke model is that you also sacrifice the premium fares for “express” trips, but the savings might work out with better service for people commuting from downtown to the suburbs.

The reason for the quote marks around “express” is that in other jurisdictions an “express” route runs along the same route as a regular route, but it skips certain spots to get further faster. So a true “95 express” might make only one downtown stop between Hurdman and Bayview, making life much better for, say, Orléans residents commuting to Algonquin College.

—

Peter Drake wrote: “To my mind, one of the benefits of deep stations is they allow a larger spread of entrances. The proposed entrances in the current plan provide coverage every block or so.”

In the initial, concept stage, Staff sold this to Council on this premise. However, as the designs progressed to their current stage, it has become apparent that the exits go straight up, because you can’t build a diagonal access without excavating all the dirt above it. So the end result is that we’ve got lots of swtichback escalators essentially going straight up. The horizontal distance covered is negligible, it’s just that most if it is done at the platform and concourse level instead of on the surface. There’s even a department-store style elevator at the Rideau station’s western entrance (with the portal at the War Memorial), where the top of one escalator is directly atop the top of the previous one, requiring you to walk the entire horizontal distance back to get up to bottom of the next one.

—

Darrell Henderson wrote: “there’s no real discussion of how a tunnel in the downtown could be an impetus for transformation of the downtown, or how it could free up space for better pedestrian facilities or bicycle lanes”

Actually, that has been a big point of conversation downtown, and I know Diane Holmes has raised it many times. That could even be her main reason for supporting it. But it’s flawed.

For one, the Official Plan and Transportation Master Plan both require any new transit corridor to have pathways built alongside it, to allow pedestrian and cyclist access to the stations. However, these are the first amputations of a hemorrhaging project budget. In the mid 1990’s when the South-East transitway was built, this component was removed from the plan to save $4M. At the time, they said the pathways would be built “when funds became available,” which is never.

The same thing happened for the now killed N-S LRT plan to Riverside South, except that one was $6M in savings.

The current plan is not a new transit corridor, so it wouldn’t qualify under these grounds, though certainly we’d want to improve Albert and Slater. If they end up building it along the Ottawa River Parkway (and I hope they don’t), that already has a pathway alongside it.

—

Getting back to my original point, an analysis of tunnel plans neglects other plans for rapid transit. As Fraser suggested, the flaws cited for dismissing surface rail in the current plan are far fewer and pithier than those in the current plan which are resolved with expensive “mitigation measures”. It’s literally two paragraphs in the whole 200 page document, and easily disputable. Politically, it didn’t need to be elaborated further because one option involving surface LRT had already died (though it shared the cluttered route with buses), and this any option involving surface LRT could be dismissed. It’s not logically sound, just a clever conjuring trick.

I’m not saying that surface is the way to go, but I am saying that a surface option has not been sufficiently considered. While Alain says that money should not be a major limiting factor, in reality it is, otherwise the plan would encourage building rail to the suburbs before 2031 instead of 63-plus kilometres expensive and unnecessary bus Transitways.

I just wanted to take issue with one of the observations which seems to be used to loan weight to the idea of the tunnel. You say “We also quickly forget that Toronto wasn’t much larger than Ottawa at the time it started building its first line.” Yeah, if we are to look at only population as an indicator, sure. But then we look at the actually scale, distribution of people, usage of space and for that matter the history of those two places and comparing 1954 toronto to 2010 Ottawa (which is a comparatively HUGE city that faces the post-amalgamation sprawl issue and a culture dominated much more by the car, and without surface trolly service, and the list goes on) sees spurious at best. The city itself has admitted that surface rail would get this city through to at least 2030, which is just about the time that a rapid LRT system under the tunnel plan would reach the suburbs.

Why Toronto? Why not a city like Frieburg, Germany, or Portland today.