You’re cycling down Bronson Street in the spring after a winter of heavy snowfall. Your eyes are trained on the cars passing through an upcoming intersection when you hit it. Yet another pothole. Pulling out your cellphone, you take a photo of the wretched hole in the road. The photo is transmitted to an online map, tagged by the GPS in your phone, alerting other cyclists and city workers of the problem.

Ushahidi is a free, open-source, crowd-mapping tool that can do just that.

The platform was created by Kenyan developers and bloggers during the outbreak of post-election violence in Kenya in early 2008. Ushahidi, which means “testimony” in Swahili, enabled Kenyans to report incidents via SMS messages to create an online map of the violence. As live broadcasts were banned, the developers created a system that used the tool most available to Kenyans – cellphones – to provide an up-to-date account and a historical record of the events.

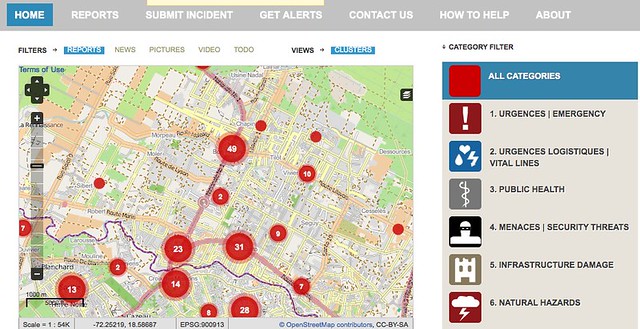

Since then, Ushahidi has been deployed all over the world, mainly in crisis situations. Anyone can download the Ushahidi platform and tweak the technology to suit their needs. The platform displays data collected and submitted by citizen journalists on an online, interactive map updated in near real-time.

When the earthquake struck Haiti last January, Ushahidi was deployed within the first two hours. Thousands of project volunteers across North America translated and geo-located over 25,000 SMS messages and emails helping to locate people trapped in the rubble. Ushahidi takes advantage of the fact that in times of crisis when infrastructure is destroyed, cellphones often still work.

But Ushahidi isn’t just for crises. The platform is as flexible and innovative as the people who use it.

Jason Nickerson, a PhD student at the University of Ottawa studying humanitarian emergencies, describes Ushahidi as a community-empowerment tool that could be employed by community-based organizations or municipalities.

Ushahidi identifies where problems are arising, he said, but those problems don’t need to be life-threatening.

“Why not potholes?”

Ushahidi has been used to track crime in Atlanta and El Salvador. In Washington, D.C. last winter, residents called the platform “Snowmaggedon” and used it to track snow removal. In Los Angeles, the system has been used to submit reports of stolen bikes and bike collisions. Closer to home, crisis response practitioner Laura Madison is putting together a team to use Ushahidi to map Manitoba’s Red River flooding this spring.

The platform isn’t a perfect tool yet. The challenge, Nickerson says, is figuring out what to do with the data that is collected.

“When does the data reach significance? To whom is it significant?”

There’s an inherent sampling bias, he says, because of the necessity of having access to a mobile phone or computer. If Ushahidi is to become a community-empowerment tool, it must be accessible to those who can most benefit from the information it provides.

This is a challenge that affects Canada in particular. As the most expensive country in the world to own a cellphone, Canadian deployments risk limiting access to wealthier demographics.

Dale Zak, a Canadian member of the Ushahidi team, says one of the strengths of the platform is that it can be adapted to meet the needs of the group employing it. Groups can choose to focus on reports submitted by text message, phone apps, or web-based entries.

The Ushahidi team is busy developing new technologies to make the platform more accessible and more usable. Crowdmap is a server that hosts Ushahidi deployments making it unnecessary for users to download the platform. Swift River is an open-source platform that filters and validates the information gathered from citizen reports. The team has developed smart phone apps for Windows Mobile, Android, and J2ME. An iPhone and iPad app is in its final stages of testing. In late November, the team released an all-around improved Ushahidi 2.0.

Ushahidi is evolving, and what’s becoming clear is that its applications are only as limited as the imaginations of its users. Its dependence on volunteers committed to their causes is both its weakness and its greatest strength.

Ushahidi is more than a platform, Zak says. It’s “a global community working together towards a common goal.”