George Smitherman’s $17.4 billion transportation platform reads like the work of a old parliamentary hand who knows a thing or two about the dark art of cabinet making, and I’m not talking furniture.

If you’re the boss, you understand that you need to dispense the bounty both geographically and demographically, taking care to pay off your base while reaching out to less adoring constituencies.

So by my count, the Smitherman plan offers a little civic something for everyone: subway extensions in Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough; just enough Transit City, pedestrian and bike lane language to make progressives look at him twice; public-private partnerships for Bay Street; free rides for seniors; and about 500 metres of tunnel for some lonely squadron of Liberal foot soldiers manning their redoubt on Mount Dennis, which apparently will become the new western terminus for the Eglinton LRT.

The plan, moreover, is vintage big-tent Liberalism, in that it unapologetically encroaches on the policies of most of Smitherman’s rivals, not to mention Mayor David Miller’s.

Lastly, the two-phase strategy — most of the $7 billion in “incremental” spending is back-loaded onto a second term — doesn’t make his former cabinet colleagues (and future enablers) look like dupes, say provincial sources, who feel his plan won’t force Metrolinx to trash their latest build-out scheme.

But while “Transit Delivered” is a textbook example of constituency appeasement, it is also plausible (except for the free seniors’ passes) from a transit policy perspective. So why, then, did Smitherman not apply a comparable level of attention to the money aspect? The omission seems like a bizarre oversight in a campaign dominated by the same.

It’s difficult to judge whether Smitherman is being sloppy or coy, but the dynamic of this race is that both Rocco Rossi and Sarah Thomson anted up financing strategies — admittedly flawed — to accompany their transit platforms.

The bulk of what Smitherman revealed on Friday (e.g., “Transit Trust,” the reliance on “triple-P” project management) had to do with bookkeeping, and thus doesn’t address basic questions: Where does he find the cash? How do the associated financing costs impact the City’s overall operating budget? And what will he do to ameliorate the increased operating shortfall of an enlarged TTC? (That last one is a question none of the subway enthusiasts have been willing to touch.)

Let’s focus for now on the capital piece.

As my colleague and Spacing columnist Steve Munro notes, the projected capital cost of the additions come to less than $4 billion (2010 dollars), compared to the $7 billion cited in Smitherman’s speech. The padding, his handlers say, is about making conservative projections, and the bulk will be spent between 2015 and 2020.

Smitherman contends that if the City outsources project management to design-build-finance consortia, it may face higher carrying costs over a longer period than would be incurred with traditional debentures. But the extra expense, he claims, will be offset because this approach allows the City to insulate itself against St. Clair West-style overruns (i.e., the design-build groups agree to deliver the project at a fixed price by a given date rather than coming back for top-ups).

Yet besides touting his own adventures with health care triple-Ps, Smitherman failed to properly explain a complicated financing arrangement and provide defensible projections as to the size of net benefit. While such methods may bring down cost, they won’t get him the whole way.

So where does the rest of the capital come from?

He insists there will be more detail later about revenues derived from development spurred by transit construction — a claim Mel Lastman made but neglected to deliver while shilling for the Sheppard line.

When asked about using asset sales to finance transit construction, Smitherman has left the door wide open. But as campaign spokesperson Stefan Baranski told me in an email yesterday, “Generally speaking, no. However, George has indicated a willingness to look at asset sales where it makes sense — for non-essential services like the Toronto Parking Authority. [emphasis added].”

Might such non-essential services include Toronto Hydro? It wouldn’t surprise me. [editor’s note: Smitherman’s campaign says he will keep Toronto Hydro public ]

But the real sleight of hand here has to do with the City’s debt level.

During Friday’s scrum, Smitherman made an oblique reference to an April 6th report from Moody’s Investor Services, which concluded — contrary to what almost everyone thinks — that the City of Toronto has an enviably low debt burden relative to other Canadian and international cities, as well as “manageable” debt-servicing costs (currently about $450 million per year).

Referencing recent council reports [PDF], Moody’s further noted that the City will have more room to borrow after 2016, when its net debt levels begin to fall as the backlog of non-transit infrastructure repair ebbs. By no coincidence, that’s also when Smitherman’s transit project spending scheme ramps up.

So why wasn’t this telling detail part of Friday’s announcement?

That’s an easy one. Smitherman would have to acknowledge that Miller’s financial management hasn’t been nearly as horrific as he’d have voters believe.

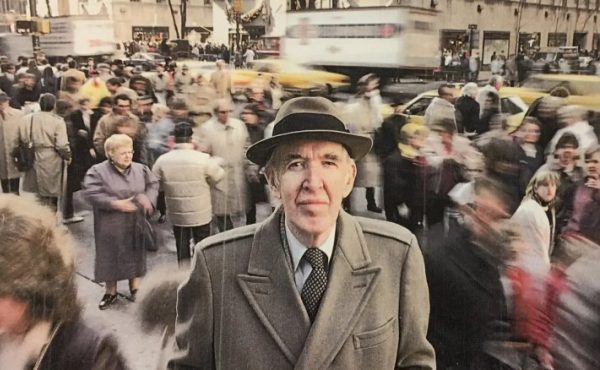

photo by Sam Javanrouh

15 comments

I’m not against design-build schemes ideologically but Smitherman has to explain how he thinks Toronto schemes would be insulated from the fiasco unfolding in London where TfL is buying out the private partners.

The usual thinking is that it won’t be a problem because the private partners will absorb the losses – this assumption is undermined by the fact that TTC left Bombardier off the hook for the failure to deliver the new subway order on time due to the bankruptcy of one of its subcontractors. BBD’s failure to monitor the performance of its subs should in my view (although I am not a lawyer, still less one of the corporate ones) have led to them being as liable for the sub failure as for one of its own making.

Smitherman’s transit train plan is taking Toronto taxpayers for an extended debt ride they don’t want to be on. It is typical of his poor fiscal budget management and waste seen from his Queens Park years. Unlike his surprise e-health fiasco, at least this time Smitherman is telling us up front how much of a financial screw up he will cause this time.

Ha ha. The truth comes out. It’s too bad Pantalone, doesn’t use these numbers in his favour to stop all this “debt reduction/cut costs” BS coming from the political right.

Another ridiculous plan for Transit without fiscal concerns. I find it funny that the “funding” in this plan comes from “Private partnerships”. As if private sector partnerships will yield billions of dollars. Who in the private sector are willing to partner or help fund/partner with a system which wastes money like there was no tomorrow by employing overpaid, underused, unskilled workers, with a fat pension/benefits?

Marcus Gee reported on the weekend that Smitherman’s plan would quadruple the City’s debt from $2.5 billion to $10 billion. As John L. notes, the current debt is serviced with annual payments of $450 million. That’s 18 percent, which seems a bit high given that government T-bills are currently yielding something like 1.3 percent.

A mortgage calculator suggests that annual payments of 18% make sense only if we are either paying too much in interest, or paying everything back unnecessarily fast given the lifespan of the investment.

I have wondered for years why politicians and journalists don’t distinguish between credit card debt (paying for ongoing expenses) and mortgage debt (paying for long-term investments) when they emote about debt and deficits. It seems to me that a $10 billion debt for long-term transit investments in a City as large as Toronto is not necessarily a bad thing, especially when interest rates are so low.

Isn’t it better for governments (and voters) to simply admit this, rather than enter into complicated leasing arrangements with private financiers, paying for the privilege of deluding ourselves into thinking we are not in debt when we are?

It is interesting to see how terrified most politicians are of explaining how to pay for stuff. Yet the Toronto Board of Trade’s report on this topic (and the news coverage of it) points out that lots of other jurisdictions have agreed to tolls, congestion fees, etc., and voted in favour of same in referenda. Is it too much to hope that Toronto voters will reward honesty in a mayoral candidate instead of gullibly buying the delusion?

It is quite simple: we need Transit City and we need tolls.

Oh, and the extra tunnelling in Mt. Dennis is unneeded and unwanted! Roll the baby strollers and the mobility scooters right on at street level! Nobody is going to tunnel under the Black Creek and the Humber River any time soon…!

My problem with private sector involvement is that the contracts are inevitably written so that any profits are grabbed by the private sector, but if there are any losses the private companies involved simply declare bankruptcy and leave the taxpayers holding the bag. Examples abound from the Pickering Nuclear fiasco to TfL to British Rail.

George had better be careful about selling off the Toronto Parking Authority. The TPA is currently able to operate public parking lots in residential areas (the TTC is the only other entity allowed to do this). This is because it is publicly-owned, and is accountable to the public interest (not only in how it operates but also in how it develops these properties). Residents who tolerate a publicly-owned lot in their neighborhood may oppose a private operator/developer who can ignore community concerns and the public good. And the sudden appearance of a private business in a residential area would become a precedent for other businesses seeking zoning changes.

But aside from all that, how much is the TPA worth? It cleared 76 million in 2008, equivalent to the interest governments paid on $2.5 billion worth of T-bills that year. Unless we’re talking a 10-figure sales price, selling off these assets is ideological, not logical thinking.

The $450-million annual payment on the City’s debt includes principal and some capital-from-current spending (paying for capital projects from current revenues rather than borrowing to finance them). Note that the accumulated debt financed projects with varying lifespans. Also, for any debt that was incurred at a time of higher rates, it is in the City’s interest to pay it down early.

John:

cannot find yr email address, so I’m using this forum to tell you how much I admire the research you’re doing on RC Harris! Keep on keeping on, and i hope that it all adds up to a bio or something big anyway.

dennis

As I say, the politics of debt mystifies me. But I assume Steve would agree that GC’s proposed transit investments are long-term (the non-magical ones anyway). As for debt incurred at a time of higher rates, I thought government debt was paid for through regular refinancing using short-term T-bills or similar. If this is not true, and Toronto’s debt is financed through longer-term bonds, then these by definition cannot be paid down early and we are on the hook for the high interest payments anyway. Moreover, the latter case would make it even more important to borrow when interest rates are low.

Oops, above should be “GS’s,” not “GC’s”; ie: George Smitherman’s

The Sherway Gardens extension has me scratching my head.It won’t be cheap or easy to put the station where it won’t be utterly useles (west of Sherway Gardens, close to the hospital). Any other location, particularly hugging the railway right-of-way, will be utterly useless. You don’t have to stand very long at West Mall and the Queensway to figure that out.

While an extension to Sherway would actually benefit me, it’s not worth the money.

George’s web site claims:

“Extend the Bloor-Danforth Subway Line from Kipling to East Mall and all the way to Sherway Gardens. This will bring significant growth and development to the city, both in taxes and also by creating jobs – both during construction, and in the long term.”

I have no idea what sort of “develpment” will happen in an area that’s bounded on the west by a river valley, has atrocious movement because the QEW, 427, and rail line are significant barriers to all forms of traffic–cars, bicycles, and pedestrians, and is a sea of parking lots surrounding big-box stores.

Better off to run the subway to Long Branch. *Then* I’d really benefit. Hey, it won’t be worthwhile, but I won’t say a thing!

Unlike John above, I’m fine with downsizing the TPA’s footprint, although I would do so by leasing out the lots to private operators with restrictive contracts such that an operator could only provide parking and if not the lot would revert to the City. Depending on the location of the lot the term could run from short (where redevelopment was expected soon) to long where parking is a long term need.

This would give the city an income stream but also allow them to be tougher in regulating parking without seeming like it’s favouring TPA over the competition. The activities of TPA in areas like podium ads (see illegalsigns.ca for instance) aren’t necessarily in sync with Toronto’s needs any more than the private companies are, and the city should be looking to promote transit and squeeze/tax parking anyway.

For anybody who automatically thinks that private sector involvement automatically means cost overruns and bad planning, one has to counter with Madrid’s experience as well as the fact that London’s buses are very successfully privately run. This is not to say that Tokyo, Seoul, and Oslo all have varying degrees of privately owned, operated, or built out subway systems.

What matters is the incentives for the private company to do a good job. In London’s case, the government tried to get the private companies to take responsibility for a whole lot of extra maintenance that wasn’t agreed to in the original contracts, but still needed to get done. It was a complex mess.

If Madrid can build hundreds of km of metro in the span of a decade and a half at a cost per km of what we’re paying for Transit City, then there’s something seriously amis. We’ve never had a full and complete top-down bidding process for a subway tunnel here, and where they do outsource they place restrictions on either canadian content, local companies, or union membership.

The TTC has done a massive amount of past and current work in house, including buying tunnel boring machines when they could have leased them from companies that can amortize it over much more work and relied on organisations with a lot more experience in digging tunnels elsewhere.