The Toronto City Summit Alliance held a roundtable event last Wednesday to discuss revenue tools that could reliably fund Metrolinx’s The Big Move regional transit plan. Among the 12 sources discussed in the TCSA report were the usual hot-topic revenue sources: road tolls, parking taxes, congestion charges, and regional fuel taxes. But it was Metrolinx CEO Rob Prichard’s opening remarks that posed one of the most interesting questions of the day. He asked: “Should any new tool that increases taxes, require a referendum?”

For many Canadians, the word “referendum” conjures up images of a very tense Provincial referendum in the fall of 1995 (as well as the spring of 1980), when Quebec’s sovereignty was being questioned. You may also remember a 2007 electoral reform referendum in Ontario. Referendums are common in the democratic process of many countries around the world, including the U.S., but have fallen out of common use in Canada. During the 2008 U.S. election, 32 referendums were held across the country asking voters to approve new revenue tools for funding transit.

There was, however, a time when referendums were commonly used as a tool in Toronto for gauging public support of new infrastructure investment. Now, with large-scale infrastructure projects like Transit City up in the air, and problems in securing funding for The Big Move plan, perhaps it’s worth opening the discussion of whether or not infrastructure referendums could ever make a return to Toronto’s municipal election ballots.

Two historical subway referendums have been held in Toronto. A century ago, when the first subway proposals started appearing, a 1911 municipal referendum asked voters:

Are you in favour of the City of Toronto applying to the legislature for power to construct and operate a municipal system of subway and surface street railway, subject to the approval of qualified ratepayers?

The public voted in favour, however the referendum was non-binding and the candidate who won the mayoralty (George Reginald Geary) opposed subway development due to the expense, resulting in the project being scrapped.

Fast-forward to 1946, when postwar Toronto was looking for infrastructure projects to put people to work. A referendum during the municipal election that year asked:

Are you in favour of the Toronto Transportation Commission proceeding with the proposed rapid transit system provided the Dominion government assumes one-fifth of the cost and provided that the cost to the ratepayers is limited to such amounts as the City Council may agree are necessary for the replacement and improvement of city services?

This time around, not only did Torontonians vote a whopping majority for the proposal, the project went ahead too. Eight years later, Canada’s first subway was opened.

Other examples of municipal referendums in Toronto include a 1930 vote to determine the fate of Vimy Circle, a roundabout that was to be located at the intersection of Richmond and University. With the stock market crash fresh in the public’s mind, voters decided against this project. Regent Park was built following a referendum 1947, in an attempt to improve the living conditions in the Cabbagetown area. More recently, a 1997 referendum was held in all six pre-amalgamation municipalities to vote on the “megacity” plan. The vote produced a majority against amalgamation, but the Harris government pushed forward regardless. This raises the question of the effectiveness of non-binding referendums, if governments maintain the ability to ignore the results.

Non-binding referendums can work. In Stockholm, a non-binding referendum was held in 2006 to decide if the city’s road congestion charge should be kept. The congestion charge was introduced in early 2006, run for a trial period of seven months, and then allowed to sit idle for three months, giving Stockholmers time to evaluate the charge. The ballot asked voters:

Environmental fees/congestion tax means that fees will be charged in road traffic with the purpose to reduce queuing and improve the environment. The income will be returned to the Stockholm region for investments in public transport and roads. Do you believe that congestion tax should be permanently introduced in Stockholm?

Voters narrowly approved the charge, despite electing a centre-right government who ran on a platform against congestion charging. In this instance, the referendum results were acknowledged, and the charges were kept.

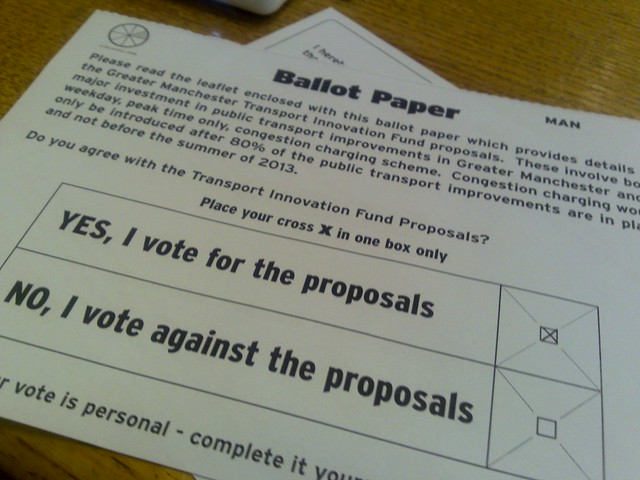

Similar congestion-charge referendums have been held in Manchester and Edinburgh. In these referendums, voters decided against introducing the charges. A major difference in these cities was there was no trial period for the charge, and therefore drivers were never able to see the congestion reduction and environmental benefits.

Would infrastructure referendums work in Toronto? Let us know what you think. Please begin your comment with YES or NO, to make it easier for us to tabulate results, and suggest what referendum question would you like to see on the next municipal election ballot.

Photos by Francisco Osorio, Richard Eriksson, and Frankie Roberto

25 comments

Look, I’m all in favour of the average person becoming more involved in the machinations of government, but I feel that today’s society is more of the “me first”type, and would not be as forward thinking or progressive as the examples the writer proffered in the article.

Sadly, I have to agree with Christopher King. In North America, it appears that people – sadly – have to be brought kicking and screaming into the 21st century.

No, in addition to society having many “me first” types, most people don’t take time to understand the issues but still believe they are experts and therefore get caught following some political rhetoric. Although also not perfect, I prefer major decisions like this to be debated and resolved by industry and academic experts.

I agree

A referendum would be fine with the informed electorate, However, the key word is “informed”, and a lot of people are not “informed”. There is also the NIMBY aspect to deal with, yes they may want something but not in my neighbourhood.

I think referenda might work better if they were truly popular – i.e. that the City of Toronto would be obliged to put citizen led initiatives on the ballot every four years. City led initiatives are likely to be opposed on spec by a loud minority which will just poison the project in the future.

The question should be: Do you support Transit City for transit expansion in Toronto or a subway-focused strategy?

The predictable results frighten the supposedly “progressives” who have full faith in the technocrats. It’s those who fear the public rather than promoting debate and diverging perspectives who hold us back.

NO

the previous responses to your poll indicate that voters are rarely able to follow ballot instructions.

No,

in addition to what was mentionned above, there would be issues of who gets to vote. Toronto citizens only, or all of the GTA/province. Infrastructure issues affect a lot more people then the people living in its immediate vicinity. Moreover, referendums in general are a very poor way of designing policies; California obvioulsy comes to mind, but even Switzerland, with its high level of social cohesiveness can get bogged down in years of debates over simple projects.

I’ll point people to California to see what happens when you put issues to the public on a regular basis. Even “no-brainers” like gay rights in the state that counts San Fransisco among its great cities can be defeated.

On the other hand. How patronizing is it of us to suggest that we know how smart people are, in general. If the state did that, suggested that we’re too ill-informed or stupid for referendums, it would make the G20 backlash look tame.

It’s no wonder the majority of Torontonians sided with the cops in the G20 debate. Who else are they going to side with? A group of educated and possible enlightened people who in general think the majority is a huddled mass of moronic sheep, too dim to make their own decisions?

So one can choose to be nannied by the state or patted on the head by the “enlightened” class. Some choice.

The most interesting thoughts I’ve heard on public participation in planning come from Andres Duany. I’ve read/heard him say that public participation is the biggest obstacle to ‘good’ urban planning. He’s also proposed that a public consultation should have the developers on one side with the NIMBYs on other and have citizens without a stake in the project and elected officials moderate between the two. The point is that NIMBYs are just as powerful a ‘lobby’ as the developers.

NO. Besides the fact that most people fail to see the big picture when it comes to things such as city building, it also seems that they get mental blinders on as soon as they hear or read of any proposed user fees, charges, taxes, etc. Most people would have a knee-jerk reaction to these sorts of referenda and would vote no without fully understanding or even fully reading the question (the latter point is easily demonstrated by several of the replies to this post).

Too often, the question is poorly framed as a “yes/no” choice, when it should be “two from column A, and one from column B”. Developers and “NIMBYs” are neither necessarily bad people. Some developers would put up the tallest, densest, worst crap possible if we let them because condos seem to sell themselves with no respect to the surrounding neighbourhoods. Some NIMBYs have a perfectly good reason for opposing proposals, and they may not even live next to the site. Is an altruistic city dweller a NIMBY just because they don’t think a new building is a good idea?

Similarly with transit, framing it as a Transit City/LRT versus subway debate is completely wrong. Both modes are required in a network, and the real question is which one in which corridor. If you want to vote to make every choice from “column B”, that’s your option, but we should not be forced to (for example) vote against the Downtown Relief line in order to get an LRT line on Finch.

In the context of Prichard’s question, would the government come out with a big publicity campaign on the “yes” side for transit funding, or would they sit back afraid to alienate anyone, and leave the real campaigning to the advocates? You can bet if the Tories get into office, they will print ballots with only one option on them.

One merely needs to look to California to see how well voter-directed economic policy works. Ballot initiatives there led to a rule that the state government cannot run a deficit; subsequent initiatives killed many new tax plans.

As a result, the state has been pretty much bankrupted. Well done, voters!

NO. Not that I hold them in high regard, but I’d rather trust an engineer when he/she tells me that we need to build something unsexy like a new sewer, than to ask a generally uninformed and apathetic public to make that decision.

No, for the reasons already posted.

The democratic system we have in place works very well: we vote for a leader or party which takes a stance on a number of issues. This means the voter must choose the person who best reflects his/her ideals and values, even if he disagrees on certain issues.

YES.

If referendums were put in place and allowed individuals to support large ideas it could allow for a system that circumvents the problem of every new government scrapping old projects. A good project, that the city has agreed upon should be followed through with.

The author brings an interesting point with the Stockholm scenario where the citizens were able to experience a trial period before voting for/against. In any scenario where an actual experience can be appreciated the public becomes far better informed and better able to make an educated decision.

It is unfortunately too often that Torontonians watch their municipal governments waste time and money. Citizens may be more willing to get involved with projects if they were given more opportunities to be involved with them (through trials) and cast opinion in favour or against (referendums). A referendum system could provide some answers to how Toronto moves forward.

Yes,

I actually agree with most of the comments above. The public is largely disconnected from most issues, but the state of our society today encourages it.

We need ways in which people can connect with their communities and be involved in it’s politics, referendums could be part of the solution.

Let people debate amongst themselves and have a reason to be informed.

This may be a scary prospect in a city where Rob Ford is second in the polls for mayor, but the status quo is not working.

Maybe we should give it a try.

Referendum question to put in the next election ballet:

“Should we regularly use referendums as part of this city’s governance?”

There was a referendum in the early 1900s that stopped streetcar lines from cutting through Fort York.

From the Oct. 2007 edition of “Fife and Drum” published by the Friends of Fort York (by Mike Filey):

“The fort’s partisans put up a spirited defence, holding public meetings, lobbying officials and prompting editorials and petitions of protest. And when in early 1907 council asked the electors’ approval to borrow 125,000 to defray the costs of bridge-building for the streetcar line, it was defeated by a margin of more than two to one. But the siege didn’t end there. Within a year council sought a Private Member’s Bill from the Ontario Legislature to exempt it from needing the electors’ consent to borrow. The request was refused by the Private Bills Committee. Not content, council tried again and, second time lucky, carried the day. Its success was thwarted, however, when the government of Premier J. P. Whitney, who was personally sympathetic to the fort, said that it would tack an amendment precluding streetcars running through the fort on any private bill.”

Full text: http://www.fortyork.ca/newsletter/F&D_10-07.pdf

Yes. Other jurisdictions have proven I think that referendums are a viable way to secure funding for large scale big ticket infrastructure projects. If a new tax were to be clearly and directly tied to a specific project I have a good deal of faith that the electorate would do the right thing.

Kevin wisely points out the results of such participation in California. The ‘public’ will often make decisions based on self interest and or short term gain. At the root of the problem is the depth and source of information that the public relies on to make ‘informed’ decisions. If anyone is really interest Nobel Prize winner James Buchanan’s The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy is a good primer.

Kevinator makes great points. The sad state of transit expansion is due in part to an uninformed public which politicians perceive as indifferent. We need to advance the issue so that average citizens of the city discuss among themselves what needs to be done in expanding transit. Referendums would encourage more interest in the issue and discussion. It would be up to proponents of issues to push their side through. Results supporting a project send a stronger message to upper levels of government that the people want something to be built and that it’s not just a matter of legacy building for a mayor or pet projects.

Yes! All sorts of people who live in the “suburbs” or drive cars recognize that transit and transportation are major issues for our city. We should have separate referenda on dedicated transit taxes and road tolls – and I think they’d pass. Because everyone is irritated by immovable traffic now and most recognize that actually building better transit – rather than just whinging about it – would make a difference.

Here’s an interesting idea.

Referendums could be a way to include people who otherwise cannot vote, and thus have no reason to be involved in city politics.

Give referendum votes to our young, I suggest starting at 15 years old.

Kids at this age are becoming aware of world issues. Encourage their involvement, give them a say. It’s their future that is at stake.

Give referendums votes to our immigrant population who otherwise have no say in their communities. We need to give people a chance to become involved citizens.

We need to engage people early, turn them into citizens instead of mere consumers.

Then we might have a chance of have having an informed citizenry conducting informed referendums.

Yes — Reading some of the comments which argue against the referendum concept citing an “uninformed” citizenry as the key reason for avoiding them, one wonders whether democracy makes any sense at all. Cynical, I’d say. If people are not capable of making decisions on referendum issues, how will they ever choose individuals to represent them in government — particularly when those choices involve considering many, many more sophisticated and various concepts than a question or two posed in a referendum? I would like to think that, if properly engaged, the populace at large (and that means everybody) makes democracy work — and referendums have a long, vital history within the democratic system.