The history of Jarvis street is filled with intrigue and murder. Today, the street still faces ongoing conflict and controversy reminiscent of its creation.

Jarvis street, like so many other Canadian streets, is named after the man who originally owned the property. William Jarvis was the Provincial Secretary and Registrar of Records from 1792-1817, and he acquired the property of the modern day Jarvis street because it was granted to him upon his appointment as the first Secretary and Registrar of Upper Canada. This type of gift was a common perk among the city of York’s first officials, bestowed by Governor Simcoe in the 1790’s. Unfortunately, Jarvis was not very competent in his position, and he left his job along with a huge debt to his son Samuel.

Samuel Jarvis was able to successfully petition the Governor in Council in 1822 for some vague wrongs that he perceived were committed against his father and in compensation he received a large sum of money. From this money he built a house at the intersection of modern day Shuter and Jarvis street. This estate had hazelnut trees in front of it, which is probably the reason it was called Hazelburn, and it was built on the 100 acres of land Samuel had already received from his father. The house was described as a handsome two-storey brick house with a wide veranda, surrounded by ten acres of lawns, orchards and gardens. Today the legacy of Hazelburn continues even though the estate no longer exists, as Hazelburn is the name of a federally funded housing co-op at Jarvis and Shuter streets.

However, Samuel Jarvis did not retire to live a quiet life at his estate. When he was 25 years old, Samuel fought a duel with 18-year old John Ridout, apparently due to bad feelings between their families. The story goes that it was one of those old-fashioned duels, with pistols and pacing and firing on the count of three. Supposedly, Ridout anticipated the count of the duel and fired on two, narrowly missing Jarvis. Samuel Jarvis fired on three and killed Ridout on the spot. Despite being arrested and briefly jailed for murder, Jarvis was acquitted of all murder charges.

In the middle of all these historical conflicts pertaining to Jarvis street, lies the spirit of service of William Jarvis himself, and this reflects how modern Jarvis street has evolved to provide a variety of social services for Torontonians such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army. Jarvis street houses a very large Red Cross building to provide community assistance and extensive housing facilities for those in need. The Jarvis street Salvation Army also adds to the communal, supportive nature of the area. Thus, in the same way that William Jarvis was rewarded for his service to Canada, modern day Jarvis street has evolved to serve the needs of Torontonians.

Other highlights of the street include the Allen Gardens, a botanical conservatory housing rare plant life from all over the world. Jarvis street also has a focus on education with the Jarvis Collegiate Institute and Ryerson University located nearby to the west. 222 Jarvis street is an interestingly designed building and one of the architectural features of the downtown. Shaped somewhat like an upside down pyramid it houses government offices that beckon to the original spirit of Jarvis himself as the city’s first Provincial Secretary; that is, in providing service to society.

Jarvis street runs into the St. Lawrence Market which is one of Toronto’s largest open concept markets where vendors sell fruits, vegetables, meats and unique goods. Next door, the St. Lawrence Hall was the main centre of civic and social life in Toronto in the late 1800’s and is protected today as a National Historical site.

Today, Jarvis street continues to evolve. In 2009, on the first anniversary of his death, a section of Upper Jarvis that houses the Rogers Communications headquarters was renamed in honour of Ted Rogers. Recently, this has been the least controversial change to happen on Jarvis street, with the bike lane controversy causing headlines and heated debates, both on and off the street.

The reasons to remove the bike lanes appear to be two-fold. Some argue that since there are bike lanes on Sherbourne street, a major artery which runs parallel to Jarvis, the bike lanes are redundant and Jarvis should be reserved for vehicular traffic only. All cyclists should be pushed onto Sherbourne street to reduce congestion on Jarvis. It is argued that it would be safer for cyclists to not be on Jarvis street and traffic would move more efficiently as drivers would not have to be concerned with looking out for cyclists. Additionally, narrowing Jarvis street to accommodate the bike lanes has done nothing to improve vehicular traffic and congestion either.

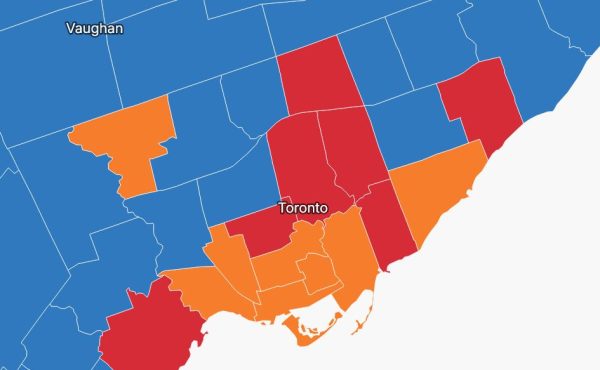

The second reason to remove the bike lanes seems to fall under Rob Ford’s broader mandate to end the war on cars. He believes that cars should have priority and having to share the road with cyclists is simply an unnecessary burden. This push-back against cyclists on Jarvis can be seen as part of a wider city movement, with bike lane being removed on Birchmount road and Pharmacy avenue in Scarborough as well.

The Toronto Cyclists Union has launched their campaign to save Jarvis Street, as a thousand cyclists depend on the Jarvis street bike lanes. The Toronto Cyclists Union issued their official response to city council’s decision to remove the bike lanes, encouraging their supporters to contact their city councillors to prevent the bike lanes from being removed.

Does the resolution on bike lanes need to resort to a duel where both sides lose, including Toronto taxpayers? The potential cost to remove the bike lanes exceeds the cost of creating them. The Jarvis bike lanes cost Toronto taxpayers $75,000 to install last year, but will cost approximately $200,000 to remove once the Sherbourne bike lanes have been completed by the end of 2012.

With Jarvis Street back in the news recently, the future of the bike lanes remains uncertain. Hopefully, all parties can find a more positive way to move forward and leave the spirit of conflict in the past for Jarvis street.

4 comments

Great story!

The more bike lanes the better. I’m in favour of leaving the bike lanes on Jarvis and expanding the Sherbourne lanes however as a daily commuter cyclist I’m convinced that cyclists unconsciously choose the smoothest path. Jarvis has terrible road pavement quality and for that reason I don’t use it. The south end in particular is very dangerous with pavement “lava-type” flows from heavy truck traffic that make curb lane riding awful.

Parliament on the other hand, repaved in 2010 is a joy from Dundas to Queen.

Actually, the cost to remove the bike lanes is closer to $250,000, in part because the wiring for the problematic switchable middle lane has to meet current electrical code. The article states, “narrowing Jarvis street to accommodate the bike lanes has done nothing to improve vehicular traffic and congestion either” but misses the point that it has much improved cycling and pedestrian safety with little affect on vehicular traffic.A city study found that the number of cyclists has tripled. Look at all the new highrise condos on the street, one 44-storey and two others under construction at the corner of Charles Street East and Jarvis, one at Adelaide and Jarvis, and another planned just up the street. It’s increasingly a residential street. Removing the bike lanes will increase congestion if instead of opting to cycle these people take their cars instead. What kind of downtown do you believe one, one which caters to motor vehicles or one which values people?

Traffic congestion is caused by cars, not bikes. Toronto is perhaps the only major city in which accommodating the automobile continues to be the basis of urban design. As the city continues to grow bikes, busses and feet become more important. Spending taxpayers’ money to remove existing bicycle lanes is not only bad management but shows a frightening lack of foresight.