Since Toronto’s amalgamation, there’s been very little re-tooling of the governance model foisted upon the region during Harris years. Paul Bedford, our city’s former Chief Planner and appointee to Ontario’s Transit Investment Strategy Advisory Panel, spoke with Spacing to unpack a few ideas that might improve our awkward teenaged governance model.

SPACING: Over 16 years after amalgamation, what does our government model look like in Toronto? What’s missing?

BEDFORD: It’s a model that is too big and too small at the same time. It’s too big because so many people find it very difficult to interact, and engage with the city the way they used to when there were the six boroughs, because they felt their local government was much closer to them, more accessible. That’s the big part: people feel distant. And I think it’s too small, in many ways, because it has problems interacting with the larger region – with the GTHA and the Greater Golden Horseshoe – because we’re all in this one region, we’re all in this together. And the question is: how do we all plan, work, develop transit facilities as a region, not just one city versus another city? I think that whole business of what I call “thinking and acting like a region” is really a key theme. And the other key theme is having a governance model where people can feel like their voice matters.

SPACING: What are other governance models we could look to?

BEDFORD: One of the ideas is simply about breaking a big place – which this amalgamated city is – down into more bite-sized pieces that people can interact with. And there’s lots of cities that have done that. New York is one place, (obviously it’s very big with eight plus million), they have 59 community boards that are established in different pieces of geography that represent about 250,000 people each. And those are all comprised of citizens, not politicians, and they have a strong advisory role – each community board is residents, and business, and developers, industrialists, and property people. So it’s pretty democratic. That’s one model: I know Los Angeles, Seattle, many other people have what they call neighbourhood advisory committees. But the thing is, if we go down that road, it has to be a made-in-Toronto model.

SPACING: You’ve advocated a mix of local and district representation on council, similar to the old Metro Council system. How might that improve decision-making at City Hall?

BEDFORD: Let’s just assume, for the sake of argument, that you keep 44 councillors. It’s important for any councillor to think, not only local or ward-based for obvious reasons, but also city-wide. Generally, the bias of our governance system is: most councillors really care only about the ward, or about the local stuff, and the city-wide thinking sometimes doesn’t receive the attention it should. I was just saying: take roughly a quarter – which is 11 out of the 44 – and devise the system where 11 people were elected on a district basis, and everybody else would still be elected on a local ward basis, so you get a mix of people that were primarily thinking city-wide, versus those that were thinking local. They’d all still be on the same council, but it’s trying to get the best of the Metro and local governance models built into the amalgamated model.

SPACING: We seem to have some regional antipathy between the former municipalities that comprise the city. How does that effect governance in Toronto?

BEDFORD: Part of that is historical, part of it’s cultural, part of it’s “we did it my way and I don’t like your way.” I think the key there is one size doesn’t fit all, and you have to have a strategy that respects the local differences – of built form, and character, and objectives of different communities across the city – yet still have a cohesive city that works. What works downtown is not going to work in suburban Scarborough. I just think our governance model needs to be improved, to be more sensitive to the need to address both local and city-wide issues. And secondly, to harness the energy that exists in communities all across the city that is now not really being harnessed. A lot of it’s frustrated.

SPACING: Heading into an election, what should people be asking of prospective councillors and mayoral candidates?

BEDFORD: I think it would be very refreshing for candidates to at least engage with people about “gee, how can we make amalgamation work more effectively?” That’s the key question, both for a city-wide agenda and a local agenda.

SPACING: Every once and awhile, someone floats the de-amalgamation balloon, suggesting we should go back to the way things were.

BEDFORD: That’s the easy out. But we’re not going there. All the stuff that we’ve done over 16 years, I think amalgamation clearly can work if you make some changes. The problem with the way it was done: there was no plan. If you go back and compare when Metro Toronto was formed in 1954, Premier Leslie Frost, two or three years prior to that, they had a huge commission of people studying different governance models around the world, and what would be best suited to a made-in-Toronto solution in the early 50s. And they came up with the two-tier governance model, it was brilliant and wildly successful, and copied around the world. And then we got rid of it. Let’s make amalgamation work more effectively, let’s get the best of both worlds here.

A condensed version of this interview can be found in the latest Fall 2014 issue of Spacing, available on news stands now.

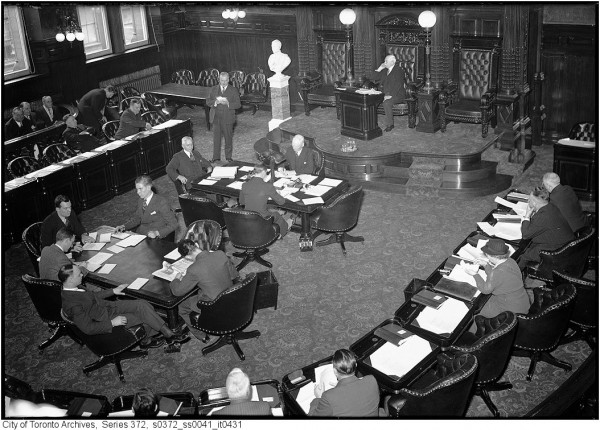

Photo courtesy of Toronto Archives