Every municipal planner knows that when the City convenes a public meeting to consult a community about a proposed project, the people who tend to show up are well-educated, middle-aged, home-owning residents. Young people, tenants of all ages, newer immigrants, and those who are marginally housed, often stay away. If a young person of colour shows up at a meeting, the odds are that s/he is a planning student.

The demographic bias in favour of the already empowered is reinforced by the process. Public meetings are called when a property owner proposes a building that is taller or denser than allowed. This means that consultations put people in a reactive role– a situation that encourages negativism. Equally important, public consultations proceed one at a time and cover a small area (even a single building), with little or no reference to what is going on a few blocks away. Due to the narrow scope, inequalities between and within neighbourhoods rarely become visible.

In an attempt to respond to these structural problems, the City of Toronto’s planning department has created a “Planning Review Panel (PRP),” composed of 28 volunteers chosen to be broadly representative of Toronto by age, race, and housing status (tenants vs owners). The panel has gender parity and includes at least one Aboriginal resident.

According to the City, the PRP will meet six times a year, and give feedback on planning in a less reactive and myopic manner than is the case at public meetings. “Our city’s motto is ‘Diversity Our Strength,’ yet we know traditional planning processes don’t always hear equally from Toronto’s many communities,” states chief planner Jennifer Keesmaat. “The [PRP] is an exciting way to bring new voices to the table, as a complement to the hundreds of consultations we host each year.” Daniel Fusca, the planner in charge of the project, adds that the board’s role is to offer strategic advice to the planning department, not city council (which decides on particular developments).

But is it possible to go beyond the reform-minded ideas that informed this project to re-think the City’s process for the hundreds of everyday consultations on specific developments?

An experiment in community consultation, carried out in 2013-14 by a small volunteer group in the Riverside and Leslieville area, shows there are viable alternatives that can result in more inclusive and meaningful consultations in neighbourhoods where hearing the voices of marginalized residents is particularly important. The members of Planning South Riverdale (PSR) knew that long-time residents, many disabled or living on social assistance, would not show up to the city’s consultations if they were run in the usual manner.

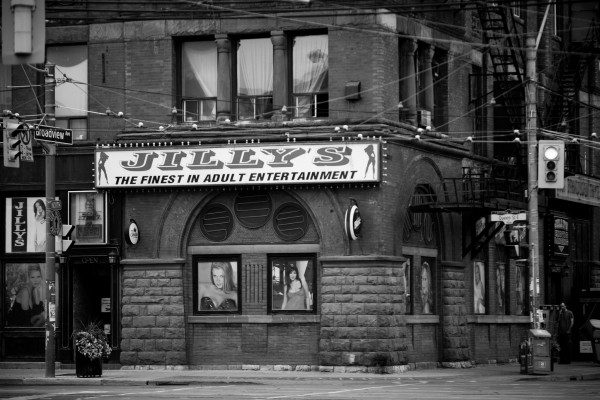

While gentrification is hardly unique to South Riverdale, this area had gained widespread media attention because of the closure of Jilly’s, a venerable hotel and strip bar at Queen and Broadview, notorious for its aggressively downscale “Girls Girls Girls” neon signs. After learning about the new owner’s plan for a boutique ‘heritage’ hotel, people across the city became concerned about the potential displacement effects of this development on Queen St. East.

The tenants who lived above the Jilly’s bar were relocated by the local community mega-agency WoodGreen. But PSR’s members knew that the area, which had been low income until the 1990s, contains several shelters and a significant amount of social housing. The group worried about whether the remaining low-income neighbours would feel increasingly marginalized in their own neighbourhood.

Knowing that calling a public meeting was not a good method to solicit the views of marginalized citizens on planning decisions and policies, the PSR members went to them instead. Four focus groups were held in spaces that were already familiar, and participants were asked about their experiences with stores and services on Queen Street.

The results shed much light on commercial gentrification. These long-time residents did not “feel welcome,” as one older single man put it, in the area’s gentrified establishments. The most frequent complaint was the absence of any Tim Horton-style coffee shop: the residents reported that they felt alienated not only by the high price of lattes but by the feel of upmarket espresso bars. Someone noted that a small park behind the Jilly’s hotel had been used to socialize and smoke by people living in nearby supportive housing, but when condo owners with dogs pressured the city to create a fenced-in dog park, an important public space was lost.

The most novel finding was that when a business catering to low-income residents (e.g. a bank or a pharmacy serving those on social assistance) moves out, they often end up taking all of their business to a different, not-yet-gentrified neighbourhood, even if these residents have to walk quite a distance. Thus, rapidly rising commercial rents can end up having a snowball social effect.

What lessons can be learned from the PSR’s pilot project? In my view, parts of some planning consultations could be contracted out to community groups and centres, rather than professional consultants. Such local groups know who in the area is at risk of displacement, and how best to reach out to them. Of course, all interested individuals ought to be allowed to participate. But as the push for the new review board intimates, when the City relies on the traditional model, it will only hear from the already empowered.

In an increasingly unequal city, planners need to find new ways to ensure that those most at risk of being displaced and disempowered have their voices heard – even if that means going to where they are, and relying on intermediaries who have the right local knowledge.

photo by Mark Hawk

* * * * * *

Planning South Riverdale conducted a series of focus groups as part of its consultation process, and a report of the findings can be found here: PSR CONSULTATIONS REPORT.

Mariana Valverde is a professor in the U of T Centre for Criminology who works on urban and municipal law and regulation. She is the author of “Everyday law on the street: city governance in an age of diversity.” (University of Chicago Press, 2012)

3 comments

When it comes to neighbourhood gentrification the end goal of developers will always be to move out the undesirables. As such, the end goal of municipal planners working for elected municipal governments should be the full accommodation of the displaced within their own neighbourhoods. Unless the mandate of the consultations is full integration what does it matter who’s conducting the knowledge gathering? The difference between someone telling you to get out and someone walking you to the door is little more than fake altruism.

This is a great article. I’m the stakeholder engagement guy in the Chief Planner’s Office and I’m glad the TPRP has fans. Just want to point out that the methodology outlined here is not new to the Planning Division. We’ve used essentially this methodology before, though perhaps not with homeless populations. Certainly with marginalized populations – Lawrence Heights is an example. The program there trained and paid residents to be ambassadors of the planning process, which is somewhat different, but was also very effective. For TOcore though, we will be reaching out to homeless populations in exactly this way. I don’t have too many details, but the idea is to equip local agencies with consultation kits that they can take to people where they are.

I disagree with James.

Why should the indigent have some moral claim to not being moved around as the nature of a neighbourhood changes? They have two easy ways to exercise their political power inherent to them as citizens (1) vote; (2) show up for public meetings and speak their piece. They choose to do neither of these.

We see nothing wrong with telling the working and ambitious “you want to live in a better neighbourhood, get ready to pay more money, or move.” Why is it some how wrong to tell the poor and slothful “you want to live in a worse neighbourhood, move: this one’s getting better.” What happened to “beggars can’t be choosers?”

The reality is running a city with all the programs we’d like to have costs money. Sustaining marginal housing on prime real estate is, in effect, a waste of money, or at least an opportunity of money. Asking private sector developers to do it on a large scale is a losing proposition: they simply won’t play the game if the money isn’t there for them. Guess where the money comes from for a public developer to do so?

What we should really be doing is pulling out the stops to allow for the creation of all kinds of new housing everywhere. The sudden increase in supply would increase diversity of housing options for everyone, and decrease the cost, making the issue of lack of marginal housing options less of a problem.