The 2016 budget debate, which lands today at executive committee after doing the usual rounds, has offered up a curious mix of urgency and its opposite.

On the one hand, Mayor John Tory and city manager Peter Wallace have been warning for some time now that city council needs to adopt unspecified new revenue tools meant to address not merely normal course operating pressures but shortfalls that are looking a lot like entrenched structural deficits.

On the other, the mayor’s proposed property tax hike of just 1.3% — a figure that is slightly under the Bank of Canada rate, but doesn’t reflect rising prices of food and other imports — is lower than anything the post-amalgamation council ever approved, except for the four years (1998-2000, in the Lastman era, and 2011, year-one of Ford) which featured zero tax increases (many thanks to Western University’s Zack Taylor for the longitudinal data). Soaring real estate prices have added a $100 million windfall to the land transfer tax, and so it seems almost certain that the federal budget will bring all sorts of manna for housing and transit. The message: we can relax because David Miller’s land speculation tax is going to save us, again.

So: Bad news and good news. Pick your poison.

At the risk of hurling Spacing readers into a pit of budgetary obscurata, let me further confound this ambivalent picture with a substantial, though little noted, shift in the City’s policy for funding certain capital expenditures from the operating budget – the so-called “capital from current (CFC)” or “pay-as-you-go” line item. If you don’t pay much attention to the CFC figure, don’t feel bad. No one does.

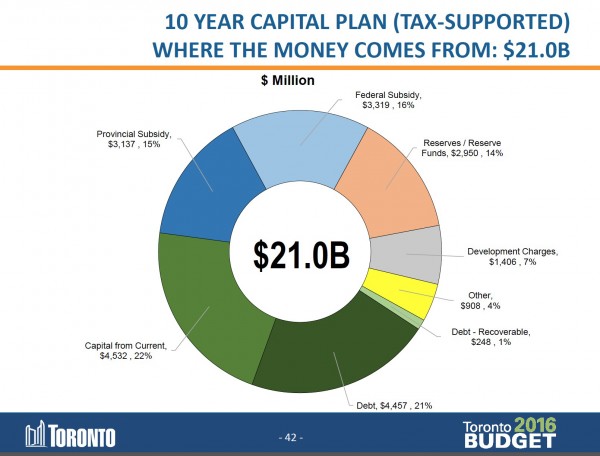

For many years, council approved capital budgets where CFC income (the dollars drawn from the operating budget) accounted for only 10 to 15% of all the sources of capital funding. The balance came from federal or provincial one-time grants, reserve fund draws or debentures.

But as the proposed long-term capital plan – 2016-2025 – makes clear, council intends to significantly hike the CFC contribution to the capital budget in coming years. By 2025, according to city budget documents, capital from current funding will rise while the debt-financed portion will fall until they’re at parity – both accounting for about 22% of the overall figure. Over that ten-year period, the operating budget will fund a whopping $4.5 billion in capital outlays. (At an average of $450 million per year, that’s roughly a quarter of the annual emergency services budget.)

Before I get into the reasons why this subtle shift presents a major funding challenge for the city’s day-to-day operations, it’s worth explaining the pay-as-you-go approach to budgeting.

If you buy something large and long-lasting, like a house or a piece of machinery for your company, it makes good sense to borrow the funds, partially because most of us can’t pay cash for major purchases but also because such outlays generate a return that exceeds the interest on the funds borrowed. But there are all sorts of smaller “capital” necessities that don’t require debt-financing: a new coffee maker, repairs to the fence, and so on. Those you can pay for from your pay cheque or whatever savings you might have in the bank.

The city takes a similar view: For the big-ticket infrastructure that lasts for decades, borrowing makes a lot of sense. But for all the myriad smaller expenditures – e.g., vehicles, computers or software licenses that need to be replaced every five or six years, small-scale projects that can be completed in a year, studies, etc. – it is prudent to just pay as you go; that’s what capital-from-current is.

In years past, council’s capital budgets depended on a far more modest draw on the operating budget. In 2009, council passed a 2009-2018 capital plan in which CFC accounted for only 11% of the long-term outlay of $28 billion. The next year, that proportion rose to 16%. By 2012, midway through the Ford era, the CFC component of had hit 20%, but fell back to 13% in 2015. Interestingly, only 10% of the 2016 capital budget will be CFC dollars, but that ratio will shoot up in coming years if the current budget plan is approved at council later this month.

Why is the City now planning to rely much more heavily on the operating budget to pay for all sorts of capital expenditures? What changed? Certainly, one can discern Peter Wallace’s influence: he came in with a mandate to impose some fiscal realism on a council and a chief magistrate notably lacking in the same.

With interest payments on the City’s long-term debt consuming a steadily expanding portion of the annual operating budget (over $600 million per year, making it the second largest expenditure after policing), the 2016-2025 budget suggests a proposed remedy to contain interest costs is for the City to borrow less and therefore limit debt servicing outlays. All true, but Tory & Co. continue to advocate for pricey big ticket projects — like the Gardiner re-build or the Scarborough subway — as well as absorb massive bills for over-runs on earlier mega projects (Spadina extension, Union Station refurb, etc.).

At the same time, the proposed 2016 capital budget doesn’t yet reflect the reality that the federal Liberals are ready, eager, and willing to transfer huge sums to municipalities to build assets like new transit lines and social housing projects.

The Trudeau government won’t reveal its spending plans until March, so the City obviously shouldn’t be counting its stimulus dollars before they’ve hatched. Still, the federal largesse — all of it in the form of project dollars — will almost certainly relieve some of the pressure on the capital budget, and that infusion should ripple through other parts of the city’s spending plans, including the reliance of operating dollars to finance capital expenditures.

The proposed 2016 budget, however, suggests the opposite. We’re actually planning to make more use of operating dollars for capital projects, not less.

Outside the antiseptic world of budget documents, what happens if the city, over the next decade, does begin to rely far more heavily on pay-as-you-go project financing than it has in the past?

It’s difficult to say with precision, of course, but the overall impact, as Parkdale-High Park councilor Gord Perks predicts, is an increasing squeeze on the City’s day-to-day needs: recreation and library programs, planning processes, salaries for civic workers, bus frequencies, subsidies for daycare and housing… the list goes on. In some cases, maybe a squeeze may be helpful and long over-due, such as with the police budget. In other cases, vital services will just get whittled away while user fees go up.

We’ve seen the rising CFC show before, incidentally. Three years ago, when the Ford administration slashed borrowing and increased the use of capital-from-current, the Wellesley Institute slammed city council for short-sightedness. “In this interest rate environment and market,” according to the Institute’s assessment, “this plan will defy economic sense, starve the operating budget, and threaten the good repair of Toronto’s future.” The macro conditions haven’t actually changed all that much from then to now, except that John Tory’s proposed tax-hike for 2016 is even lower than the rates approved by council during the Ford era.

The point is that the city’s largely over-looked plan to lean far more heavily on pay-as-you-go capital financing is merely the latest piece of evidence in the long-running narrative about the structural failings of post-amalgamation Toronto’s operating budget. That’s not a new story, of course, but it’s one that becomes ever more gnarly and difficult to untangle with each passing year. When the big new transit lines — all of them adding to the TTC’s operating shortfall — start to come online a few years hence, those fiscal pressures will become even more intractable.

If Wallace does ante up some new proposed revenue sources to help fund the complex needs of a big city like Toronto, and if council can resist the temptation to behave myopically, then the City might get itself to a place where this sort of creative accounting doesn’t end up impacting people’s lives. Indeed, as Perks argues, the City needs to boost taxes and borrow more to take advantage of low interest rates if it wants to deliver both the hard and soft services the residents of this city need.

Until city council takes that step, however, we can just think of that escalating capital-from-current line item as a kind of fiscal barometer, its every rise bringing us that much closer to the point where the math no longer makes any sense at all.

photo by Adrian Berg (creative commons)