A few years ago, University of Toronto Schools teacher Josh Fullan and I concocted a transit game for the students in his Maximum City program. Each group gets $15 billion and this task: spend the money to build new transit in Toronto. The kids choose the technologies and the routes and the stops, subject to basic principles and parameters – everything from benchmark cost-per-kilometre figures for BRT, LRT, and subway, to the importance of filling out the network. Then they draw the proposed routes on a Toronto map and defend their choices.

Fullan has given this exercise now to thousands of teens around Toronto. I have adapted it for use at the university level, for Ryerson journalism and planning students, who must apply more rigorous analyses, from selecting corridors with redevelopment potential and traffic generators to subjecting their budgets to contingency amounts and figuring out how to cover the operating shortfalls.

But if Fullan and I were smart, we’d package up this exercise as an urbanist board game and sell it to the City of Toronto for use in its endless cycle of transit consultations, including the latest set, which began with much fanfare last night. I’m guessing we’d make a small fortune.

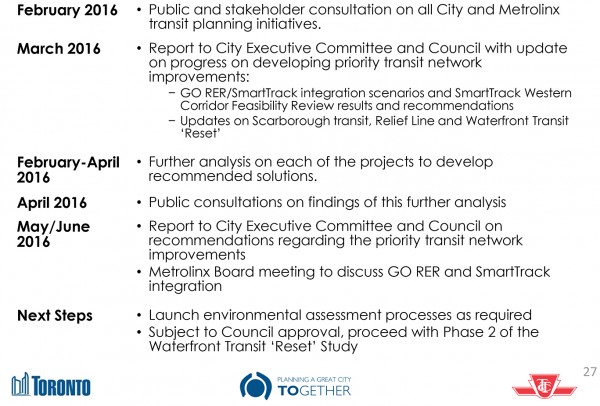

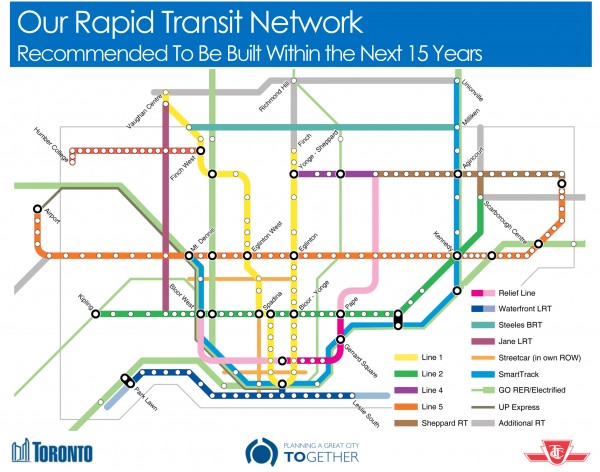

This current round includes the obligatory fantasy transit maps, which we’ve seen in various forms many times before, up-beat talk about the waterfront LRT and the Downtown Relief Line, and the self-assured timetables for action, which feature, in this instance, more utterly improbable implementation horizons, with dramatic changes by 2031.

By way of reality check, the Toronto-York Spadina Subway extension traces back to a 2005 council motion, and its completion is not expected until late 2017 or early 2018 – a 13-year delivery window. The City and Metrolinx, in the consultation documents made public yesterday, claim they will aim to finish a long list of projects, including several huge ones with no funding, within the next 15 years.

At the first session last night, the facilitators presented a 28-slide deck, which is also available on the City’s website.

The last slide says only this: “Questions?”

Okay, I have one: Who pays?

Here’s another: Why don’t we start with the money, as Josh and I have done with our nifty little transit planning assignment, and then work backwards, creating a network that ticks off functional boxes and stays within the budget allocated?

That’s an easy one, I know. We have to make sure we don’t put the funding cart before the political horse. The money, in theory, will appear when the politicians, having been deeply moved by the feedback of that tiny minority of commuters who participate in these sessions, steel themselves to conjure up the funds through some confection of taxes, levies and grants from the other orders.

But the reality is that the money flows in all sorts of illogical and politicized directions, irrespective of the findings of consultations and the recommendations of experts. Today, everyone is worshiping at the altar of evidence-based decision-making, including the same people who made stupid choices yesterday. Tomorrow, some other set of priorities and pieties will prevail. And so it goes.

The problem with the never-ending consultation treadmill is that it creates the illusion of action while sucking up valuable time. We’ll go through the motions, with no discernable result except that officials get to re-learn what they and the 1.8 million daily users of the TTC already know, which is that we need more transit and a proper network so the Yonge/Bloor bottleneck doesn’t implode.

Consider, by way of evidence to back up my allegation, the contents of Slide 27 (below). The next five or six months will be dedicated to an $80,000 consultation process and much report writing, followed by sessions of the executive committee and the Metrolinx board. Tellingly, there’s no target date on that slide for actions that represent genuine progress, such as the commencement of EAs, which compel the city as proponent to reprise these consultations and do more report writing (more opportunities to sell my game!).

At least the EAs would represent meaningful progress. I don’t want to be dunder-headed about this, but it’s not at all clear to me why we can’t dispense with the usual dance of the seven veils and move to that moment when the executive committee makes an actual, honest-to-goodness decision by approving a staff report authorizing EAs and planning studies on the corridors laid out on those lovely maps.

Why shouldn’t we take that step, say, this month, so Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, keen as they are to spend billions on infrastructure in March’s federal budget, have a crystal clear sense of council’s intentions? Why are we offering up process in the guise of decision-making?

At this rate, those transit EAs may not get going until early 2017, which means council and the province might not be approving them until… Gulp.

Here’s my point: Mayor John Tory’s election brand was all about getting Toronto moving, but it seems we’re doing the exact opposite. As far as I can tell, we’re blithely consulting our way right into the early innings of the next municipal election cycle, which, it must be said, coincides with the next provincial election cycle (June, 2018).

What happened to all of Tory’s out-of-the-gate urgency? And, more importantly, how long will it be before Ontario Progressive Conservative leader Patrick Brown is all over the Toronto’s airwaves, bleating about subways and those horrible LRTs and Liberal indifference to the long-suffering people of Scarborough?

We’ve all seen this movie before and we all know how it ends. Instead of more earnest communing with the public, it’s time for the City to fast forward.

4 comments

Great piece John

I think the answer to your question is basically this: Tory committed too much to SmartTrack being built as proposed (without actually justifying the line, especially the Eglinton West section) in his 7 year time line. This made the Eglinton West corridor study necessary, which delayed moving forward by 1 year. To a lesser extent, his commitment to running SmartTrack with a TTC fare and on GO corridors also delayed moving forward on local transit for 1 year.

SmartTrack was credible enough, simple enough and ambiguous enough to get through the campaign but this left Mayor Tory caught up by his own plan. That said, if John Tory has run with the idea of SmartTrack to Mount Dennis and an extension of the Crosstown we’d be in a different situation, but that would have put him right up against Rob Ford who was attacking him on Eglinton Ave West and questioning if Smart Track would run at street level.

I’m impressed with the compromise produced by the Transit Toronto planning team led by Ms. Holden, and certainly see it as an improvement over last decade’s Transit City (though the Transit City LRT Plan and Transit City Bus Plan are clearly the foundation here) and Network 2011.of the 1980s. I’m pleased to see that the vision includes subway, GO/RER/ST, LRT, BRT and enhanced buses and streetcars. If we can find a way to pay for it (let’s have that Revenue Tools conversation again, along with a fare integration “Fare Conversation), we’ll end up with a complete rapid transit network (barring a few missing links) and different modes applied as needed.

This is a far cry from our Dire Straits of the past three decades….Subways or…and for…Nothing (Traffic for Free).

Regards, Moaz

That is a wonderful game to play with students to get them thinking about how to build transportation in Toronto.

I would only make one suggestion: Include bicycle infrastructure. I bet teenage students would have excellent ideas about what to build. Including systematically eliminating all rat-running “cut-through” car traffic from residential neighbourhoods. As was done in virtually all parts of all cities in The Netherlands. See:

http://www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2012/04/100-segregation-of-bikes-and-cars.html

That’s what I want for Toronto. And I suspect that teenage young adults will as well.

Toronto has one of the world’s best transit systems – on paper. And that’s precisely where it will remain, in effect, a virtual system. Where transit is concerned, Toronto is a backwater.

This latest transit plan is nothing “new,” nor is it a compromise. It is a compilation of past plans all put together on one map so that it looks prettier and more impressive, and more expensive. Though it has become somewhat de rigueur to be critical of Transit City, the fact is that TC succeeded where others have not. It was simple enough and affordable enough to get more of it approved and funded, while giving the City some much-needed additional transit capacity quickly (at least in transit terms). No plan will be able to withstand the 4-year election cycle. History has shown us that the more extensive and expensive the plan is, the easier it is to just keep studying and consulting and talking, while actually spending and building little. This latest plan solves nothing, but it takes us back to the old days when big plans were published and approved and only a few small, largely useless pieces ended up getting funded. It’s fine to have a big plan, but the focus must always be on the priorities that are doable. Transit City survives, even in the latest plan, as the best chance for this city to move forward quickly with new transit capacity while work continues on funding the really important, but “scary expensive,” subway relief.