By Laura Berazadi

In Canada, the first integrated public art program was established in 1961 when the Province of Quebec introduced its Art in Architecture program, which allocated one percent of construction costs toward the realization of site-specific fine artworks. Later, the mandate of the federal Department of Public Works’ Fine Art Programme (1964-1978), which can be traced to the Massey-Lévesque Commission and its Report, stipulated that one percent of the construction costs of new public access federal buildings would be allocated for works of art, and that those artworks would be integrated with the architecture.

Much like the U.S. General Services Administration Art in Architecture program, which emerged around the same period, the Canadian initiatives from the mid-20th century developed from a desire to foster a national identity and use culture in public spaces to do so. Today, over 50 Canadian municipalities have formalized public art policies and programs and, in the United States, there are currently more than 300 cities with public art ordinances as part of their planning mandates.

The Federal Transit Administration, in the United States, published a policy circular in 1995 titled ‘Design and Art in Transit Projects’, which encouraged including art in mass transit projects, noting:

“The visual quality of the nation’s mass transit systems has a profound impact on transit patrons and the community at large. Mass transit systems should be positive symbols for cities… Good design and art can improve the appearance and safety of a facility, give vibrancy to its public spaces, and make patrons feel welcome. Good design and art will also contribute to the goal that transit facilities help to create liveable communities.”

A series of Case Studies in Sustainable Transportation assembled by Transport Canada in 2011 echoes the Federal Transit Administration’s earlier message:

“Over the past 20 years, a trend has emerged of incorporating public art into transit operations. Cities and transportation agencies are coming to understand the many benefits of public art, which range from increased ridership through improved aesthetics and increased vibrancy, to improving relationships with the community.”

These quotations offer a bit of insight into new ideas about the purpose of integrated public art that became more prominent in around the 1980s and later. Specifically, programs that integrated art with public infrastructure sought to become more receptive and adaptive to the histories of project sites, more inclusive of community uses and requirements, and more open to new and varied media.

In Toronto, the Spadina Subway line, which opened in 1978, included at least one public artwork into each new station. The public art on the Spadina line is quite varied and is illustrative of the shifting approach to public art at the time. Some artworks are highly integrated into the station finishes or fixtures and support the overall design intent of the project, whereas others are standalone pieces, unconnected to their surroundings.

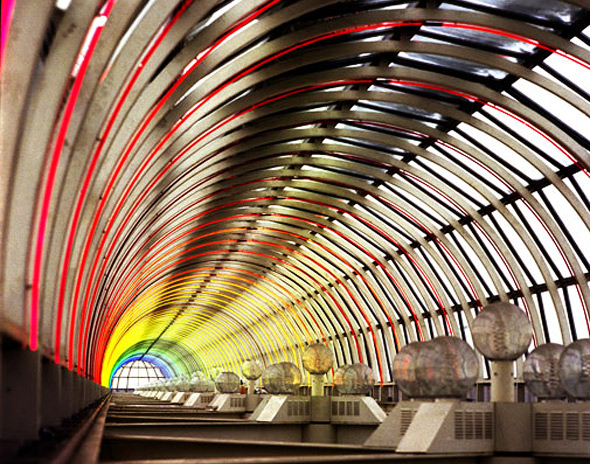

There was also a willingness to work with new materials and methods. One example of this is Michael Hayden’s ‘Arc en Ciel’ installed at Yorkdale station; a 570-foot-long light sculpture of neon tubes that pulsed with a spectrum of colours in sequence with the trains below. Due to an insufficient allocation of maintenance funds, this artwork was removed in the early 1990s. Today, most public art programs reserve at least ten percent of the artwork budget for specialized conservation and maintenance.

Transit systems form a critical component of civic infrastructure and transit art programs, in general, have objectives that may include building civic identity and pride of place, enhancing the transit user’s experience by making it user-friendly and aesthetically pleasing, lending a unique identity to transit stations or systems by introducing variability through artworks, fostering creative collaboration, and making transit reflective of the communities served. This type of artistic collaboration, consideration of audiences, and use of varied media is illustrated by the following recent examples.

Wrapper (2012) is a permanent work of art by Jacqueline Poncelet at Edgware Road station in London, UK. Created in vitreous enamel, the artwork clads the building and perimeter wall in a patterned grid. Each pattern communicates a different part of the surrounding area, resulting from the images Poncelet developed through her research over a period of three years prior to installation. Located in the urban setting of central London, Wrapper intersects a varied landscape of buildings. Resembling an immense patchwork, Wrapper weaves together imagery taken from local history and the surrounding environment. In Wrapper, and throughout Poncelet’s artistic practice, patterns and colours are employed in deliberate arrangements. “A pattern not only speaks of other places, but of changes in our culture and the passage of time”, says Poncelet. This permanent, integrated artwork is highly responsive to its local context and open to interpretation. In conceiving the artwork, the artist considered the way it will be viewed by residents and transit users alike.

![4 Wrapper, 2012, Jacqueline Poncelet [image thelondonphile.com]_resized](http://spacing.ca/toronto/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/05/4-Wrapper-2012-Jacqueline-Poncelet-image-thelondonphile.com_resized-600x400.jpg)

The Fulton Centre is New York’s first fully digital transit hub, which has 52 state-of-the-art digital signage screens. All of the digital screens present Barcia-Colombo’s video simultaneously for 30 seconds every 10 minutes, six times per hour. Commuters are able to watch a different sequence each time they pass one of the video installations. The benefit of a program like this is that, typically, the advertising contractor will cover the expense of the hardware and can offer screen time for digital artworks since it obtains revenues through advertising. Because updating and replacing digital screens can be cost prohibitive for an art program, this type of arrangement works well as it allows the transit agency to direct the majority of the art budget to the artwork content. And, while attempts at digital art programming have occurred locally on a smaller scale, the possibilities today, for commissioning site-specific screen-based artwork and for artists to experiment with new vertical format video at significant scale, are unmatched.

The qualities of public space influence our experiences and shape our days. In this way art, and good design, contributes to city building. An agency of the Government of Ontario, Metrolinx was created 10 years ago to improve the coordination and integration of all modes of transportation in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. Metrolinx is an increasingly public player in shaping the form and quality of the civic realm that accompanies regional transit infrastructure, and the provision of high quality and durable integrated artwork in the public realm is an important part of this transformation.

As an agency with a regional mandate, Metrolinx is currently in a unique position to develop a consistent, system-wide approach to art in transit, avoiding piecemeal tactics. With new stations and systems being constructed, Metrolinx can link architectural expression to art in a way that is meaningful for riders, and provide works that enhance the public’s experience. By involving artists early, we can maximize opportunities for collaborative design while remaining cost effective by building in solutions from the start. A new integrated art policy, established in 2014, provides clear guidelines for the implementation of a new transit art program, projecting forward into a future in which multiple operators and brands, various procurement methods, transit-unique operational requirements, and complicated stakeholder needs feed into the selection and production of artworks to enhance the public spaces we are building.

Laura Berazadi is the Senior Advisor, Integrated Art at Metrolinx. She is developing and implementing the public art program for capital projects in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, as part of the Metrolinx mandate for excellence in design. She is currently working on the art program for the Eglinton Crosstown LRT, which will include six major public art commissions integrated into the design of the intermodal stations, a mentorship program for local emerging artists, and a unique specialization in screen-based digital artworks, to be a distinctive feature of the Crosstown.

The Artful City is a bi-weekly blog series exploring the evolution of public art and its role in the transformation of Toronto, both the city fabric and the community it houses. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org