At last year’s Camp Wavelength festival, the enchantment of Friday night still buzzing, Jonathan Bunce (“Jonny,” he insists upon) and his Wavelength organizing partners stood on the beach on Toronto Island. A white dingy, captained by a man in a Super Dave Osborne-esque, all-white jumpsuit came slowly towards the shore. With one foot up on the hull of the boat, à la Washington Crossing the Delaware, ‘Dingyman’ (as they now call him) beached his small boat in front of the festival’s organizers.

“He was like, ‘hey, what’s up guys? Is Kyle here?!’” says Bunce. Before he or Aaron Dawson could answer, Dingyman piped in: “He was like, ‘Hey, hang on — you guys want a beer?’ and he started passing out cans of beer to anyone who was there,” he says. “He figured out Kyle wasn’t there, but he hung out for ten minutes and had a beer with us.” And then, continuing his bacchanalian pursuit of whatever party Kyle was at, he disappeared into the night, heading (puzzlingly) directly away from the beach, rather than along it. “The next morning, the three or four of us who were there had to corroborate to make sure we weren’t hallucinating.”

These moments, bizarre as they are summer-defining, can be hard to come by in the 416; they require a state of unwind that, more often than not, is inverse to one’s proximity to the city. That they are rare makes them that much more valuable. “For me being a city boy,” says Bunce, “I haven’t had a lot of those kinds of experiences.”

Camp Wavelength is a music festival that wants to be unlike any other festival, committed to bring those hazy, summer moments within reach of even the most committed urbanites. As the only camping-and-music festival in Toronto, the experience it aims to create differs sharply from the big, commercial festival experiences that, over the last decade and a half, has exploded in popularity in Toronto and across North America. That’s by design: “Camp Wavelength is an alternative to the typical summer festival,” says Bunce, “where the local band is playing at one in the afternoon and a beer is $11.” This year’s festival will be the second time it has been held, and organizers are hoping they can repeat and build upon last year’s successes. With 25 bands and 16 visual art and mixed-media performances, and a goal of 1,000 attendees, the festival is notably smaller than other big name events. (Wayhome, for example, had an attendance of around 40,000.) It’s small size, though, should not be a measure of its success — small and tight-knit is just the way Wavelength likes to do things. “It lets us be nimble,” says Bunce.

Held between August 19th and 21st, the festival is designed to showcase and promote the diverse range of art and music that Toronto has to offer. “We’re not just booking a lot of sound-alike indie bands,” says Bunce, who excitedly describes the range of genres — the festival offers a mix of indie, hip-hop, free jazz, rock, world music, etc. — showcased by the festival. “Other people [referring to festival organizers] feel like they can’t take the risk of mixing audiences […] A mandate for diversity means you need to live up to it.”

That mandate for diversity means promoting not only lesser-known bands, but making sure to promote different kinds of bands, something that is often forgotten when programming festival lineups. For festival organizers, this presents a chance to showcase a wider range of musical cultures on the same stage — the Toronto band LAL, for example, offers a unique blend of different world and electronic music traditions. By doing so, the festival is able to push a diversity agenda. “It’s still an issue, but I feel like it’s slowly improving,” says co-organizer Aaron Dawson, of Toronto’s music scene in general. “People are pushing, [and we’re] shaking people out of their comfort zone.”

Camp Wavelength also places significant emphasis on bringing visual art together with music. For Dawson, who is in charge of organizing the visual art component, the emphasis is on creating atmosphere. “The island is such a magical place, and we’re looking for ways to enhance the natural, magical beauty,” he says. Sixteen art installations — a mix of visual and performance art, the bulk of which are by Toronto artists — will help create the feeling of having your “head in the clouds,” says Dawson.

For the past 16 years, Wavelength has been a cornerstone of Toronto’s indie music scene, serving as equal parts concert series and musical incubator. Their regularly-held concert series remain a staple in the indie music scene, and their successes are evidenced on the posters of much larger festivals across North America: Arcade Fire, Broken Social Scene, Grimes, and Tokyo Police Club (to name a few) all owe part of their success to Wavelength, where many of them played their first shows. Though it has been in many ways a patron of Toronto’s music scene, it is a product of it as well. “It was started by people from bands,” says Bunce (who then rattles of a handful of bands whose names, to anyone without his somewhat encyclopedic knowledge of early-2000s Toronto indie music, may as well have been in a foreign language).

Part of what makes the festival tick is its setting. Partnering with Artscape Gibraltar (the festival’s “spiritual home”) on Toronto Island allows Wavelength to host an event that is unique in many ways. On top of the camping offering, “no other festival has a beach,” says Bunce, where many attendees, performers, and organizers congregate as the nights wind down. Other benefits are more intangible: the island setting enables a sort of urban escape. “Escapism is sorely needed to hit re-set, and to make a weekend a weekend,” says Bunce. This is no small undertaking, since getting people there and back to the island is a constant challenge. Last year, Bestival (an electronic music festival) was marked by long lines for return ferries, and there were reports online that people were jumping and climbing on to the side of the ferry, just to get home. (Mercifully, this year’s incarnation was moved ashore.)

On the southern shores of Toronto Island, Camp Wavelength isn’t far away from the city — not in any technical sense, anyways. Indeed, that it isn’t far away geographically speaking is one of the festival’s main draws. But there is a kind of distance between the city and the festival: “There’s nothing like it in Toronto,” says Bunce. “In such a frantic city, it’s such a chilled out, relaxing, warm, friendly environment.” Distance, though, exists in more than just proximity. For Camp Wavelength, it is distance by way of respite — respite from the city, respite from the standard festival experience, respite from the mundane — that brings the festival both close to home, and not.

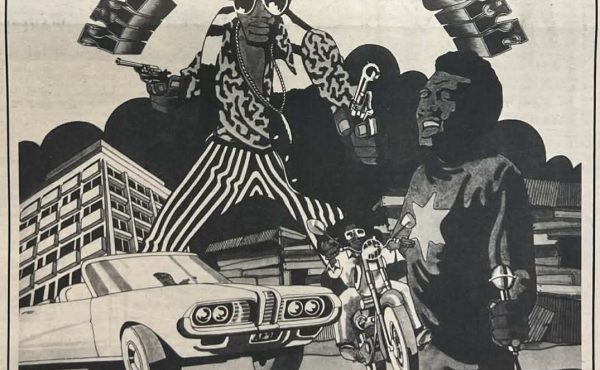

Both images courtesy of Stephanie Keating