At a moment when over 80% of Canadians live in city regions, the challenges related to all aspects of achieving a sustainable future are piling up. The good news is that cities are inherently great problem solvers. Given the right circumstances, the sheer force of compression makes them crucibles of innovation, opening up new possibilities and ways of doing things through the inventiveness of many autonomous actors.

I have been involved with Sidewalk Labs since 2015, when I was invited to a series of brainstorming sessions in New York which brought together an international group of prominent urbanists and leaders from the tech world. The premise was to identify the major challenges facing cities and explore what technology could, or should, contribute to their solution.

Advances in technology inevitably play a critical part in the evolution of cities. How they are absorbed, and what impacts they have are open questions. We have good examples and uncomfortable ones. The uncritical euphoria with which we embraced the internal combustion engine in the decades after World War II led to many unforeseen consequences as we reshaped the urban world around the needs of the car. As we recover from that excess, we now have a new and pressing set of challenges in the digital area.

The questions for me often come down to how a ‘human-centred’ urbanism could be aided by technology, not be subverted by it. Could we assess potential solutions against human values and decide when to say no, not exactly, bend, inflect and choose. As ideas emerged in the debate, it was clear that there were great potential rewards but also risks and tensions around the possibilities for dehumanizing relationships and surrendering of privacy. Once again, mobility is a good example. How could we ensure that the arrival of autonomous vehicles would not be an invitation to more sprawl? How could we blend the capacity of this technology with advancing active transportation and face-to-face human interaction?

As the ideas for Sidewalk Lab took shape, it became clear that what was needed was a ‘test bed’ — a place to proactively try out these concepts in a real urban place, not an artificial tabula rasa. In other words, a partner city with complexity, context, many actors, its own momentum and real city characteristics.

After examining hundreds of possible candidates, Toronto presented itself as an ideal location for Sidewalk, Google’s urban innovation offshoot. The goal: to see how technology could engage the contemporary city. After all, Toronto’s approach to immigration has produced unequalled diversity, a spirit of openness and a growing tech sector. And with three levels of government committed to Waterfront Toronto’s unfolding redevelopment plans for 800 acres of east downtown land, we seemed like an ideal place to try out new ideas to address the major problems of urban living, such as high housing costs, commute times, social inequality, climate change and even cold weather keeping people indoors.

When Waterfront Toronto issued an RFP for the L shaped 12-acre site at the Parliament Slip, the specific opportunity presented itself. Rather than seeking a developer in the traditional way, Waterfront Toronto was seeking an “innovation and funding partner” for this pivot point, which is a gateway site to the 800 acres of the Port Lands.

With Waterfront Toronto’s decision to select Sidewalk, a period of deep dive discovery is being launched as a joint effort to explore what a new kind of ‘technology assisted’ mixed-use, complete community on Toronto’s eastern waterfront might look and feel like.

Over the coming year, Sidewalk has committed to spending an unprecedented US$50 million on a yearlong discussion, including meeting with citizens, governments, universities and others, about what the project should be. The goal is to come up with a model that Waterfront Toronto and Sidewalk will find worthy to continue through a partnership that both sides say could spill into the rest of the Port Lands. This will not be a standalone effort. Sidewalk says it would have an “insatiable” appetite for partnerships with other companies, including local tech start-ups, as well as universities and others on the build-out.

There are, of course, many big questions and challenges to be addressed during this period, including legitimate concerns around privacy and use of data. Sidewalk and Waterfront Toronto have given assurances security and privacy protection will be baked into the new infrastructure. But ultimately, with many eyes on the project, the City and civil society will weigh in to negotiate the rules of engagement.

Why is this worth the risk and potentially be so beneficial for Toronto? We are in the throes of an astonishing growth spurt. Our systems are strained; established ways of doing basic things are stretched to the limit and beyond. We need breakthroughs and places to experiment and innovate. But as we know, change is hard. Regulatory structures and operating mechanisms that may have served us well in the past are now impediments. We have a need to test them against new realities — to modify, innovate and introduce creative tension between what is and what could be; and to ask the `what if’ questions in fundamental ways. The Sidewalk partnership may just provide the catalyst, R&D resources, and the time and space we urgently need to help us make the leap in critical areas.

While nothing has been determined, some of the things that could be explored in this urban test bed include (but are by no means limited to):

- radical mixed-use combining housing for all ages, incomes and capacities, employment including, offices, workshops, studios, stores, cultural spaces in a more malleable, fungible building fabric than we are accustomed to, underpinned by cutting-edge technology;

- a greater range of mobility options supporting current transit plans, walking and cycling, including self-driving “taxi-bots” controlled by app services, with self-driving buses to follow;

- alternative means of collecting and sorting waste utilizing new technologies and removing the need for city garbage trucks rumbling through streets;

- weather mitigation features including wind shields and possibly heated surfaces could double the time people spend outside and encourage cycling and walking;

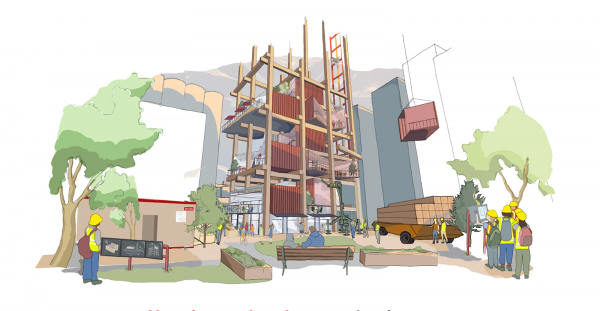

- wood-composite modular buildings, able to be quickly modified for a variety of uses which could be fabricated in the area prototyping the use of new materials;

- innovations in regulation and financing identifying areas that need to be changed or modified to allow for desirable outcomes that in place rules never anticipated. .

These and many other ideas are not technological gimmicks. They go to the heart of how we will live together in the city. By being combined and interrelated in a test bed area, their cumulative impact can be vastly greater than if they are scattered throughout the city. But ultimately, these technologies are scalable and exportable, and will have application in the Port Lands, throughout the urban region and around the world as we learn to use and manage the array of new means available to us in getting to a more sustainable urban future. As other cities have demonstrated, we are part of a great collective learning curve as we take turns innovating in different ways.

This may be Toronto’s turn to take the lead.

Ken Greenberg is a planner and author of Walking Home: The Life and Lessons of a City Builder (2011). He currently serves as an advisor to Sidewalk Labs. Follow him on Twitter at @KGreenbergTO

One comment

One has to wonder though: Why does it take an outsider, for whom serious questions are being asked, to change the City’s approach to altering planning for the better? I’m aware of a number of applicants in the past looking to seriously shake-up the backward and staid way of ‘doing things’ in Toronto? (Ont Planning Act permitting, of course, another subject…)

I’m certainly not the only one suspicious of WT and Council being ‘sweet talked’ on this.

It has a distinct whiff of ‘seduction’ by a ‘smooth and trendy spiel’. I may be too cynical, but past experience invokes a sixth sense on this.

It’s not so much what Sidewalk is promising, some of it looks very interesting. It’s the question of why all of these ‘innovations’ were derided and denied by The City in the past when proposed by others?

Trying to get Planning to accept anything proven elsewhere is like pulling rotting harbour pilings. Unless, of course, they’re seduced by avarice.