An old aphorism about elections attributed to former Canadian prime minister Kim Campbell is that the campaign trail is no place for thoughtful debate over serious issues. Did Toronto election 2018 live down to that billing? Yes and no. In all the obvious ways, this was a dreary and depressing contest whose mojo was destroyed by the premier of the province. At the same time, the campaign featured a reasonably robust discussion about the pace and volume of affordable housing development, which was a welcome highlight in an increasingly unaffordable city.

As ever, there were all sorts of topics that deserved an airing but didn’t get one. Here’s my list:

Councillor Workload

Truly, the Doug Ford-shaped elephant in the council chamber for the next four years. While the topic of councilor workload didn’t receive much attention, the question of how the 25 members of council carry out their duties will be a giant issue in coming months, and no one really knows how this problem will resolve itself.

With the doubling of ward size, it seems highly likely that councillors will require additional resources and office staff in order to attend to constituency concerns across much larger geographies. I’m not talking about calls that could be fielded by 311, either. Councillors who actually show up to work are keenly aware of their offices’ roles in resolving local disputes, steering development applications and responding to constituent concerns. The existing staff complement won’t be sufficient, especially if the losing incumbents refuse to hand over their files. (You know who you are!)

Then there’s the governance piece. By my count, the City of Toronto currently has 16 committees reporting directly to council and 64 other boards and commissions dealing with topics ranging from aboriginal affairs to property standards. Some meet rarely and do little while others are busy and active. All include members of council.

There are only so many hours in the day. Either council will have to consolidate or find other ways of delivering governance and accountability without requiring one or more members of councillor to sit on each one of these.

If history is any guide, council will likely (or should) set up a temporary transition committee with an explicit mandate to sort through these poison-chalice problems.

While the workload file may seem very inside baseball-y, the stakes are huge. After all, the reduction in council could easily set up a vicious circle, with a less responsive city government creating more public aggravation and therefore a political constituency, four years hence, for even more drastic measures.

The Next Budget(s)

Towards the end of the campaign, there was a bit of talk about the city’s financial state, plus some bracing bottom-of-the-ninth revelations in the Toronto Star about concerns within the civil service about fiscal cliffs. In the main, the echo chamber of inflation-limited tax hikes continued to drown out other perspectives and any substantive discussion about other revenue sources.

Well, beware of what you wish for. The Ford government will soon release its fall economic statement, which is a kind of mini-budget, and there’s every indication that the Tories plan to slash provincial spending. Setting aside the predictable hyperbole about allegations of misspending by the Wynne government, municipal governments may well experience these looming cuts like body blows.

Fully 17% of the 2018 operating budget, or $2.2 billion, came from provincial grants or subsidies, much of that for cost-shared social service programs delivered by the city. As for the capital budget, $4.1 billion, or roughly a tenth of the 2018-2027 spending plan, comes from provincial grants or the provincial gas tax.

In other words, the city has huge fiscal exposure, vindicating earlier warnings from Peter Wallace, the former city manager who came to be cast in the role of the Ancient Mariner in our municipal melodrama. If Ford slashes mandated social service benefits and programs, it will create a domino effect on the city in terms of growing homelessness and other forms of social dislocation. As for those capital budget subsidies, watch out because those outlays are all about city building. Cuts there will force the next council to either ice some of the big projects, find new revenues or plead for additional funding from the federal government.

Subway Upload

I suppose if you are running for mayor and you know you may soon be dealing with a populist thug, prudence might dictate a measure of rhetorical caution on the campaign trail. And so it was, especially with John Tory. Still, the provincial government’s threatened subway upload deserved way more attention than it received during the campaign, and will soon pose huge transitional and financial questions, none of which have clear answers.

Here are three:

- If the province assumes ownership of the subways, does it also take over the long-term capital requirements – billions of dollars in future borrowing commitments sitting on the city’s books for state-of-good repairs, rolling stock replacement, technology upgrades, etc.? It would seem that the liabilities travel with the asset, but who knows?

- What happens to that long-term transit property tax levy that supports the construction of the Scarborough subway extension? The upload creates a weird inversion scenario in which a local tax is subsidizing a provincial project. You don’t need to be a genius to understand that if council decides to cancel the levy in the event of an upload, that move will track like a declaration of war to the Ford government. But still, I’m not clear why Toronto taxpayers should pay to build something the province owns.

- How does the City meaningfully and transparently influence discussions about expansion prioritization post-upload? Everyone knows York Region is pushing hard for the Yonge extension to Richmond Hill, and provincial hedging on whether to do this project ahead of the Relief Line pre-dates the Ford government. By all rights, a truly independent expert panel should be established to determine the order of operations, with the province agreeing to be bound by its verdict. More generally, I’m hoping the City will enter the upload negotiations with conditions instead of resignation. The default — and defeatist — view, that the province can do whatever the heck it wants, certainly won’t be helpful in this process.

The Waterfront

It’s easy to forget – and indeed it seemed the mayoral candidates more or less did — that the City owns one third of the hot mess that is the Sidewalk Labs/Quayside file, which is a controversy and intrigue-generating machine.

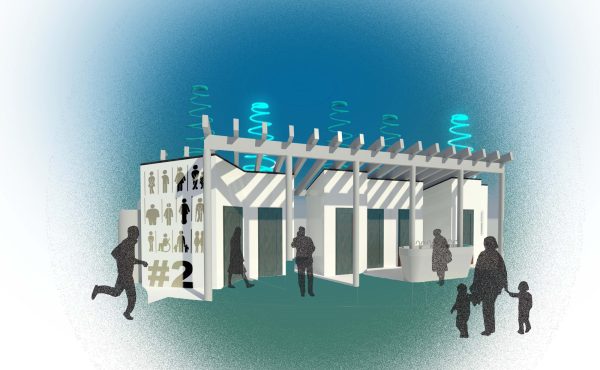

Council’s political involvement in matters waterfront is far more curated than might appear to the casual observer. Remember when deputy mayor Denzil Minnan-Wong, who has served on the Waterfront Toronto (WT) board for several years, would have routine eruptions over matters of city-wide concern, like the design of the umbrellas on Sugar Beach or the cost of bathrooms? Not long after he was elected, Tory similarly mounted a noisy campaign to bash the agency over its handling of the Queen’s Quay reconstruction project and cost over-runs that were a surprise to no one involved in what turned out to be an extremely complex undertaking.

Yet we’ve heard nary a peep of criticism from the mayor about Sidewalk’s latest tribulations. What’s more, the matter of the City’s involvement in, and guidance over, this nebulous tech play made virtually no appearance in the campaign. But the basic question remains as pressing now as it did a year ago, when Sidewalk made its splashy debut: Why should a private company deploy sensors in public space to monitor and measure the way individuals move around urban precincts?

It’s not certain where the Sidewalk Labs’ plan is going. But given the sustained controversy (high profile resignations, conflicts over oversight, etc.), the fact is that the next mayor and council must weigh in on these questions before WT signs a final agreement with Sidewalk next year.