In the wake of Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s mid-election decree shrinking Toronto City Council from a planned 47 councillors to just 25, there has been some discussion about how such a small council will manage to populate the many council committees that do the brunt of the work. One suggestion has been to appoint citizens to committees as well, a power the City already possesses (the TTC board and the police board are examples where councillors and citizen appointees work together).

When it comes to local issues, in Toronto these are currently managed by four community councils, which roughly follow the boundaries of the six pre-amalgamation cities (Etobicoke-York, North York, Toronto-East York, and Scarborough) although only Scarborough’s follows the exact old boundaries. It would be theoretically possible to maintain four community councils (West, North, South, East) with 6 or 7 councillors each. (Etobicoke would have to stretch well into Toronto and/or North York to get the minimum of 6 councillors for a workable committee). But the Toronto Star and others have suggested these community councils could be bolstered by citizen appointees (which might also enable a less artificial division of boundaries).

On the other hand, with the enormous size of the new wards, it might be worth thinking of local government in a new way. The new wards are the size of medium-sized cities, with populations of over 100,000. Cities that size are normally governed by a mayor and multiple councillors.

Why not consider having a residents council for each ward, to deal with small, local issues? That would free up city councillors to deal with big regional and city-wide issues. In past community councils, other councillors generally deferred to the local councillor for a decision on local issues, so they were mostly dealt with at the ward level anyways. And, for residents presenting local issues for resolution, ward councils would provide a venue that would likely be more attentive than the previous community councils were.

Ward councils could harness the enormous energy visible in the City elections – in open wards with no incumbent running, and even in many of those with an incumbent, there have often been a remarkable range of diverse, often well-qualified candidates vying to participate in city governance in recent elections. But it was difficult for even well-qualified, well-connected candidates to get traction in what were already large wards, and it will be that much harder in the new enormous ones. When these candidates do not win and are shut out of the governing process, most of that civic energy goes to waste. Why not create a venue where such civic energy can be harnessed and put to use, now that councillors will have an even harder time attending to such a large population?

The ward councillors would presumably be part-time (as councillors are in many small towns), and could just receive a stipend for their participation. An ideal number might be seven per ward – not too big, but just enough to provide quorum, break tie votes, and enable diversity. It would probably work best if they represent the ward at-large – it could be excessive to try to break the ward up into sub-wards. They could meet once or twice a month, maybe in the evening given their part-time status.

Who would appoint the members of these ward councils? Whatever the process, the ward’s city councillor would probably have a strong influence. Obviously councillors are likely to choose like-minded constituents, but in the absence of such a council, the councillor would be effectively making the decisions in any case. A worse alternative would be for the City Council appointments committee to make the appointments, since in that case the Mayor and his supporters might deliberately appoint a local council that would obstruct an elected councillor they did not like, and which did not reflect the choices of the local residents. The best appointment system would be some kind of independent process that selected a representative, diverse and well-qualified range of ward council members from those who applied, but such a process can be difficult to achieve.

But an even better solution might be to elect the local councils. The City does not have the power to implement an electoral process without provincial approval (which is unlikely to be forthcoming from a Premier who says he wants fewer elected officials in the province). But, if we do establish ward councils, it seems likely that a future provincial government could be persuaded to allow them to be elected.

An elected ward council could serve as a bit of a balance to the councillor, who is currently practically a dictator in their ward. It could more accurately reflect the range of opinions, interests, and solutions in the ward, and the diverse communities within it. It could also serve as a place to develop other local spokespeople who might be able to move on to running for the councillor position in the future, creating greater challenge to incumbents and a wider variety of already-known, viable candidates for open wards.

One concern with elected councils could be dominance by slates. If a particular interest group was able to mobilize the majority of voters, it could run seven candidates and take all of the seats on the Ward council. Such a result would undermine a key purpose of the Ward councils, which is to better represent the diversity of residents and of opinions.

A possible solution could be to have seven members on a Ward council, but only give each voter 3 votes. That way, no slate could capture a majority, and different groups of interests or communities could have a chance to be represented – as well as giving greater opportunities for individual and independent candidates. There might be other electoral solutions as well, although they would have to work in a situation without formal party politics.

With ward councils in place and able to spend more time on specifically local matters than a regional community council could, a range of local responsibilities could be devolved to them, such as traffic signals, local road alterations, minor zoning adjustments, small parks, and other issues that have minimal impacts outside the ward (PDF, p. 30). How they would access the budget available for items that cost money would be something that needs to be worked out. They could also perhaps have a small discretionary budget, which could be allocated to local improvement projects, perhaps through participatory budgeting.

Issues with a more regional implication, such as major zoning decisions or decisions about arterial streets, would remain in the hands of regional community councils. They might, in turn, take on more final decision-making responsibility rather than just making recommendations to City Council.

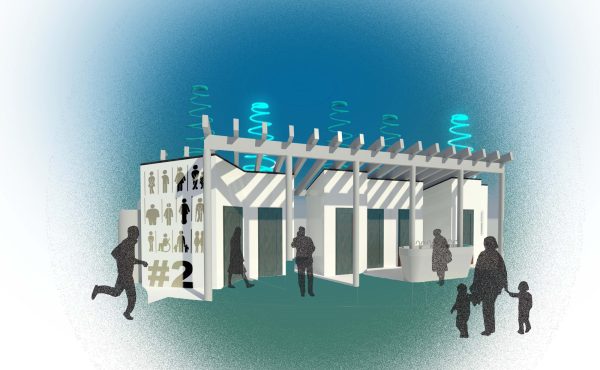

Ward councils could also encourage the City government to become more directly accessible to citizens. In a city of Toronto’s enormous geographical size, it’s difficult for residents in many parts of the city to be engaged or have access to City government. Perhaps the City government could organize itself so that there are specific staff not only responsible for but also working in each ward, on issues such as parks, transportation, planning and licensing. Even better, the City could establish Ward Halls in each ward, with a meeting place for the ward council but also for other local civic groups, and offices for staff responsible for issues in that ward. These need not be elaborate — they could just be rented in existing commercial buildings — but they would create a more accessible civic governance hub for each of the mini-cities that make up Toronto.

There are, certainly, potential drawbacks. The part-time nature of the job would favour certain kinds of candidates (retired people, freelancers, stay-at-home parents). On the other hand, the current situation also favours candidates who can take months off work to campaign, so at least it might broaden the pool.

Ward councils might also end up being very conservative and resistant to change, for example. On the other hand, it is likely that such communities already have councillors who reflect those opinions. As well, a ward council might provide space for alternative points of view who are not in the majority but who, if given a voice, could help change minds.

Finally, of course, ward councils would cost money in a notoriously penny-pinching city. In the grand scheme of Toronto’s budget, however, they probably wouldn’t cost a lot, and in exchange they could visibly improve the connections residents have with their City (and their connection with how their tax dollars are spent, if you want to look at it that way).

Toronto is often described as a city of neighbourhoods, but with the ward changes it is now also, effectively, a city of small cities. Perhaps that can be reflected in our governance structure.

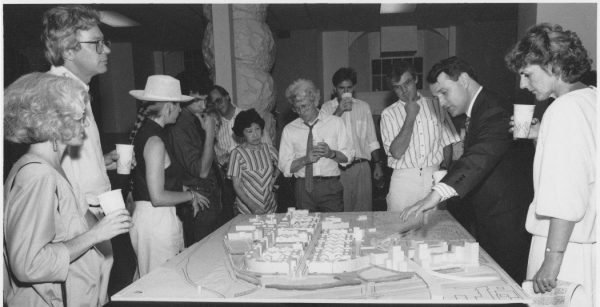

Image courtesy of City of Toronto Archives

2 comments

Hi Dylan – On the question of democratic “choosing” – by the methods you list plus others – David van Reybrouck’s 2016 book Against Elections is a goldmine of historical and international examples. Don’t be put off by the title. It’s about smart alternatives, including sortition, that work in particular circumstances.

Thanks Max – I will check it out for sure.