Hidden in the Distillery District, behind the unremarkable door of 36 Distillery Lane, is a staircase-museum. The simple stairway, necessary as an emergency exit, is decorated with industrial machinery and objects, some original to the location, others discovered elsewhere in the old complex and brought there, each one accompanied by a panel explaining its purpose and history.

The Distillery, it turns out, is full of these Easter egg mini-museums, tucked away in unremarkable but public locations, waiting to be discovered. When the complex was first being conceived, there was talk of a small museum on the location to mark its industrial history, but in the end the history was instead threaded throughout the complex (PDF), some locations more obvious than others, rather than being corralled into a single site. Each location speaks to the activities that went on in that building.

These installations are a way to recognize that the heritage value of the distillery district goes beyond the buildings themselves. It also lies in the industrial activities that took place there, and preserving the heritage of the complex demands that the work that happened there – the social and economic context of the buildings – be recognized as well.

This insight – that recognizing heritage goes beyond simply the walls of a building – was one of the themes I heard on a heritage tour organized that I was invited to join as part of the Urban Land Institute’s recent symposium “Toronto Urbanism”.

Tamara Anson-Cartwright, Program Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, City of Toronto, articulated this idea, pointing out that heritage encompasses past activities, social context, and community values. In the Broadview Hotel, this aspect of heritage is marked through a continuous mural up the main staircase that illustrates the history of the building and the surrounding community, including the building’s phase as a strip club. In another aspect of respecting the community heritage of the building, the developers worked hard to successfully relocate, within the same part of the city, the 40 or so existing residents of what was essentially a rooming house in the upper floors, in partnership with Woodgreen Community Services.

In conversation, another participant in the tour pointed to the example of the current project to rebuild Lawrence Heights, and the importance of recognizing and supporting the strong existing community based in public housing as their buildings are rebuilt and many new residents are added to the neighbourhood. In a similar vein, San Francisco is working out how to preserve the Latin culture of The Mission neighbourhood in the face of soaring real estate values.

The idea of heritage beyond a building’s walls can also mean preserving elements of buildings in new or renovated construction without maintaining the perfect integrity of the older structures. Sometimes not every aspect of an old building is worth preserving, whether because it is in unrepairable shape, or because its heritage value is limited. In such cases, elements of the building can be integrated into a new or heavily renovated structure, so that the heritage lives on in a different incarnation. The material from the old building feeds and shapes the new one. It can be compared to the way the characteristics of parents are reborn but remixed in their child, so that they live on, but in a different form.

We were shown several examples of this process. In the Broadview Hotel, the interior was in a state of collapse when Streetcar Developments took it over, and had to be completely rebuilt, preserving only the façade. But, for example, scraps of the oldest wallpaper found in the old building inspired the decoration for the walls in of one of the restaurants, and the steps of the old fire escape were disassembled and transformed into the wall art around the ground-floor elevators. Another essential, though intangible, part of the site’s heritage was the name itself – Streetcar decided to restore the former name of “The Broadview Hotel” rather than branding it with a new name. In this spirit, they also renovated the old neon hotel sign (visible on its western side above the next-door balcony).

Meanwhile, the next-door building, also purchased by Streetcar, proved to have the reverse of façadism – while its exterior was unexceptional, the inside revealed the remains of an old movie theatre, still in good shape, which was transformed into an event space connected to the hotel, Lincoln Hall. Streetcar’s Jeff Schnitter talked about the joy of such “found moments” as one of the major rewards of heritage work. The innovative Queen Richmond Centre, by Allied Properties and Sweeney & Co, similarly used materials such as wooden beams salvaged from the interior of the eastern building, which was in bad shape, as elements in the new building built around it. In another way to pay tribute to heritage, in the Distillery part of the walls of the windmill that was the first building on the site, demolished when the distillery was expanded and discovered in an archaeological dig as part of the district’s renovation project, are marked by an arc of red bricks (PDF) in Gristmill Lane.

The task of modernizing while paying respect to the heritage character of a site is a “delicate balance,” as Schnitter described it. But he and the other presenters emphasized the value that comes from the “sense of place” that is created by preserving heritage in its many forms. In several cases (some Distillery buildings, the Queen Richmond Centre) the buildings were not designated heritage, but the developers understood the extra value that came with paying tribute to the distinctive character of not only the surface of the buildings, but their history and context as well.

Heritage beyond building walls is itself, in a sense, a reverse of façadism – rather than keeping the exterior shell of a building without context, the essence of a building – its history, uses, and materials – is integrated into the next phase of the site’s life.

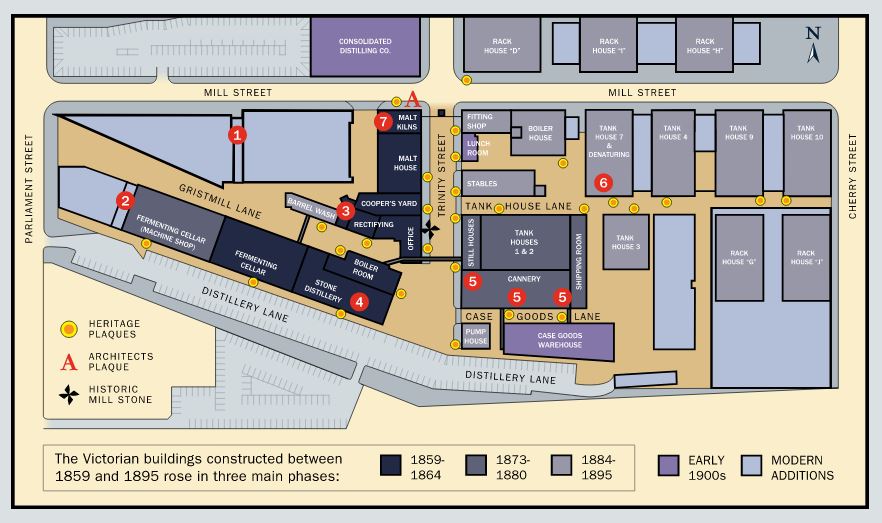

Map from www.distilleryheritage.com

3 comments

Lovely discovery of industrial heritage, thanks!

I have always felt that at least one still should have been preserved to make Artisanal Ontario Grape and Apple Brandies. To be sold in Ontario mouth blown crystal glass.

That would have really honoured the heritage value of the Distillery District

And every brick is a storehouse of energy from the firing; climate preservation means far far far more respect for existing materials and fabric, and not merely grinding them up. Considering the size of the Leslie St. Spit, which is like an iceberg, we’re flaming hypocrites and no wonder ice caps are about gone, considering momentum in atmosphere. Sorry kids….and FOrd et ill are climate criminals.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/22/climate-heating-greenhouse-gases-at-record-levels-says-un