In this year’s Ontario municipal elections, London was the first city to elect its leaders through ranked ballots, while referendums in Kingston and Cambridge both came out in favour of using ranked ballots in future elections. This year was the first one in which Ontario municipalities had the option of using ranked ballots.

But while ranked ballots are making headway in Ontario municipal elections, they have been stymied at the federal level. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s promise to get rid of the current first-past-the-post election system for the House of Commons was reputedly based on his preference for ranked ballots – but opposition to this idea was pervasive enough that he abandoned his promise. Ranked ballots for a national legislature were also repudiated in a referendum in the United Kingdom (where the system was known as the “alternative vote”) in 2011.

Why these differing directions for ranked ballots in municipal versus national elections? The answer lies in the nature of ranked ballots themselves.

Ranked ballots are ideal for electing individuals to a single office. But they do not work well for elections where voters are making their choice based in large part on their preference between multiple political parties, and where the legislature should reflect those preferences as a whole.

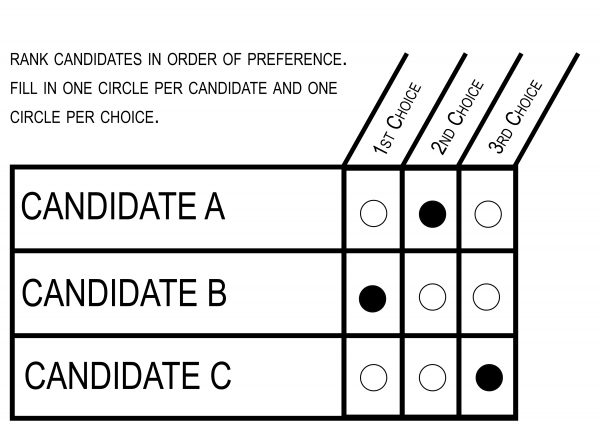

The principle of ranked ballots is simple. Like Canada’s current first-past-the-post system, voters cast a single ballot to elect a single representative for a constituency. But, rather than voting for one candidate, electors rank their candidates in order of preference. If no candidate gets a majority right away, the bottom candidate (or candidates below a threshold) are dropped, and their votes are redistributed to the second choice on those ballots. The process continues until one candidate has the majority of the votes.

In an individual race – such as a race for a party leader, where a similar system has been in effect for all political parties for many years – the system guarantees that the winner has the most widespread support among the electors and therefore a clear mandate to represent them.

In Ontario, municipal elections do not feature political parties (although candidates may be privately affiliated with one). Thus, every race is decided on the basis of the appeal of the individual candidates. Ranked ballots ensure that councillors and mayors have the support of the majority of the voters in the area they represent. There are many other benefits, too, such as removing the need for “strategic voting” and making it more viable for a wide range of candidates to run (because there’s no fear of “splitting” the vote and because voters are not afraid of “wasting” their votes on less prominent candidates).

However, in a multi-party system where the legislature is meant to represent the overall party preferences of voters and well as individual representatives for each constituency, ranked ballots can lead to unbalanced legislatures that are even less proportional than first-past-the-post results.

Imagine, for example, three parties, left, centre, and right, who split the vote evenly – but the centrist party is everyone’s second choice. It could end up winning far more seats than it got first-choice votes, because supporters of the other parties tend to gang up with it in preference to the opposite extreme.

This situation is no doubt why Liberal leader Justin Trudeau favoured the system – the Liberals are the second choice of most NDP and many Conservative voters, and would probably gain a disproportionate number of seats under the system. It’s why the United Kingdom referendum was sponsored by the centrist Liberal Democrats, too. It is also, of course, why other parties opposed these proposals.

That’s why, for multi-party legislatures, systems of proportional representation are more effective than ranked ballots if there is a desire to get more accurate representation of voter preference for the various parties than what the first-past-the-post system provides.

The exception to the rule that ranked ballots don’t work well with political parties is a two-party system, notably in the United States. In the US, the two parties, Democrats and Republicans, are not only dominant politically, but they are entrenched in many ways into the electoral process. In such a strongly established two-party system, the danger of gang-up votes is lower, and instead the problem is that it is very difficult for independents or smaller parties to have an impact – in part because people do not want to “split” the vote in a way that would allow the party they oppose to win.

So ranked ballot voting in the United States provides a way for independents or third parties to have a chance in the face of the two-party duopoly. (It could also be argued that US elections are somewhat more about the individual candidate than in multiparty legislatures like Canada’s). This year’s US midterm elections were the first case where ranked ballot voting was used in the national elections, in Maine. (Although runoff votes – somewhat similar to ranked ballot voting – have been used in several states for many years).

It’s useful to keep in mind this distinction between individual and multiparty elections because it means that the issues that make ranked ballots unappealing for national elections are not relevant to Ontario’s municipal elections. In Ontario cities, where mayors and councillors represent only the citizens in their city or ward and do not represent a party, ranked ballots provide a way to give voters the widest number of candidate options, identify the most widely acceptable choice for an elected representative, and ensure that representative has a clear and unequivocal mandate.

(In Toronto, although City Council had earlier specifically asked the Ontario government to introduce the ranked ballot option for cities, and although polls suggested a majority of citizens support the idea, City Council reversed its position and voted down ranked ballot voting in 2015. However, Toronto could still, like other Ontario cities have done, hold a referendum on the issue in the next municipal election. If you like the idea of ranked ballots being used for Toronto elections, there’s a petition you can sign.)

Image from rcvmaine.com

4 comments

1st Fallacy;

The author writes; “Ranked ballots…do not work well for elections where voters are making their choice based in large part on their preference between multiple political parties, and where the legislature should reflect those preferences as a whole”.

The Truth;

Electors in each community vote for a representative for that community. While the candidates expressed affiliation with a Political Party may inform the elector, that affiliation is not set in stone and may be withdrawn at any time, as happens, and, as is a neccessary check and balance against potentioal tyranny from the Leader and or private club called ‘political party’.

Ommission 1;

The author writes; “The (counting) process continues until one candidate has the majority of the votes.”

The Truth;

The winner can be declared with 50%+ of “remaining eligible votes” which may easily be less than 50% of the initial number of participants.

Fallacy 2;

The author writes; “In an individual race – such as a race for a party leader…the system guarantees that the winner has the most widespread support among the electors and therefore a clear mandate to represent them.”

The Truth;

It often occurs that the Leader owes their victory to the last set of electors, and not to their original supporters, and as a result serves that small faction while ignoring the core that put them on the ballot in the first place. The mandate is not clear, it is very muddled.

Unfortunately I have run out of time to continue right now; rest assured I could go on and on.

Bottom line – Ranked voting has merits and drawbacks in democrcay. Proportional Representation is not democratic as it empowers private clubs and worse the leaders/elites of those clubs, directly in between the people and their voice in Government.

It sure sounds like you could go on and on. And on. And on. And on.

I joined your Facebook pedestrian group. I was shocked by what a load of astro turf it was. I left after I realized all it was was drivers telling pedestrians not to get uppity and to be happy with whatever gains they had been given. It was appalling.

So I take any voting advice with a giant lump of salt. In fact I would go so far as to assume it’s the wrong advice.

That’s not how Facebook groups work, Quinn. They’re discussion groups, we don’t control what members say, any member can express their opinion – we don’t censor them just because we disagree with them, or because what they say seems kind of clueless.